Special Collections acquires poet Phillis Wheatley’s earliest works

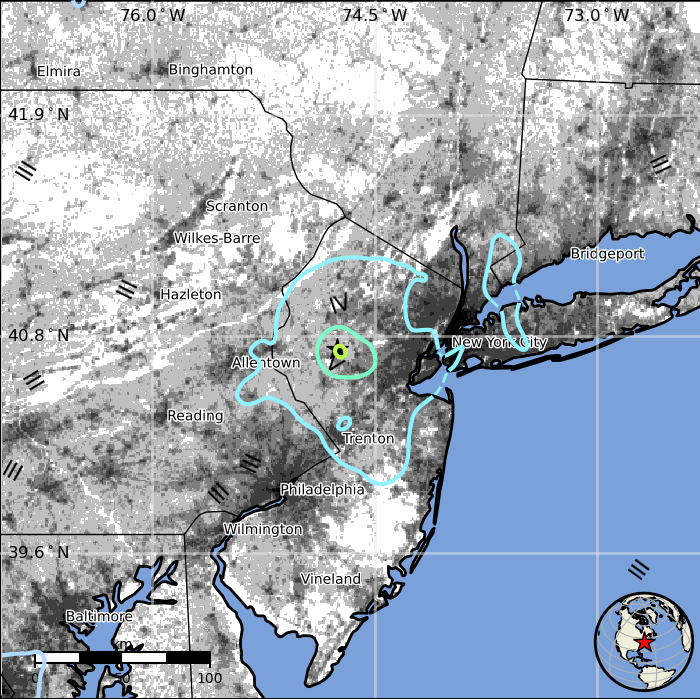

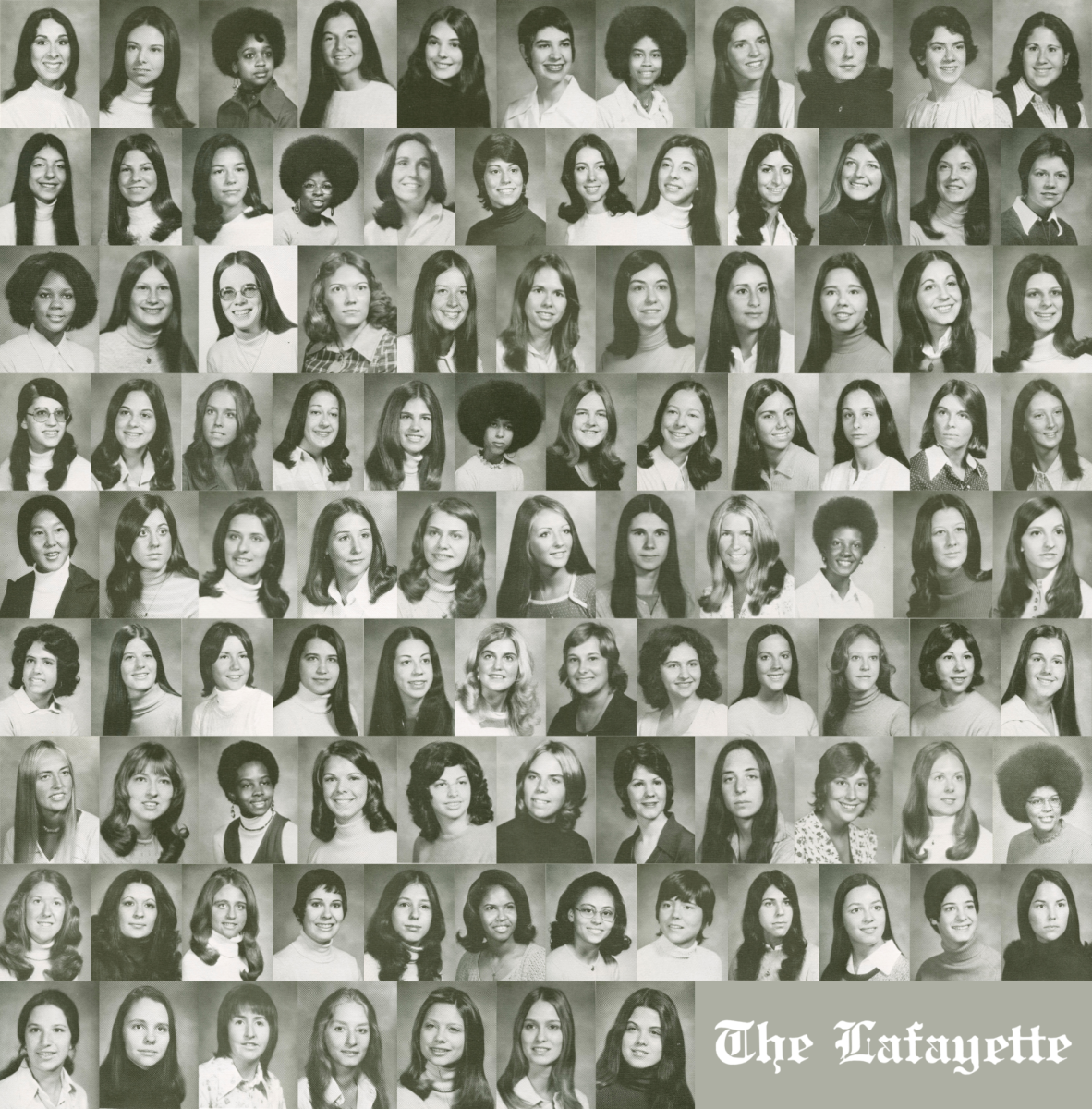

Phillis Wheatley is the the first African American to publish a book of poetry. (Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art)

March 11, 2022

You have probably seen the portrait before: a young Black girl sits at her desk. One hand clutches a quill, nib poised over the page, and another hand cradles her chin in deep contemplation.

The subject of the portrait is Phillis Wheatley, the first African American to publish a book of poetry, and now, you can view what are believed to be the earliest appearances of Wheatley’s poetry without leaving Lafayette’s campus.

Special Collections recently acquired two London-based publications from 1772 and 1773: “The Annual Register, or A View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year 1772” and “The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle,” which contain the earliest known appearances of Wheatley’s poetry. Both publications feature her poem “Recollection.”

“This is a very 18th-century thing to do, to choose an abstract concept and basically do philosophy in verse,” English Professor Christopher Phillips said of the poem. “It’s a very sophisticated thing to do. It’s one of those things that not every poet can pull off.”

“For [Wheatley], I think it was a chance to show, ‘Hey, I do belong in these literary circles. I do have the training to be able to do this,’” Phillips continued.

Wheatley was a West African girl who was abducted at around the age of seven. She was brought over in the Middle Passage and sold as a slave in the Boston area in the 1760s. After quickly learning English, she started writing poems when she was 11. She published her first and only full book of poetry in London in 1773.

According to Phillips, Wheatley is heralded by some as the “godmother of African American literature.” However, the characterizations of Wheatley have fluctuated with the constantly changing political climate.

“People thought, ‘Well, she’s too imitative,’ or, ‘She’s too neoclassical.’ Some people would go a step further and say, ‘Well, she’s a race traitor. She’s acting too white,’” Phillips said.

“In the last thirty, forty years, there’s been a big reassessment of her work saying that, actually, she’s using a lot of tropes of white culture to bring in some really interesting critiques of what she was going through, what she saw going on in society,” Phillips continued.

According to Director of Special Collections and Archives Thomas Lannon, the acquisition of these Wheatley works is part of an effort to diversify the college’s rare books collection.

“A collection shouldn’t be seen as something that’s static. It has to change,” Lannon said. “The thing is that you can recognize biases in a collection. And so there should be more African American authors.”

Special Collections aims to continue diversifying its collection by acquiring works from all over the globe. Recently, they have acquired new items from Japan, Mexico and Cuba.

“How can we diversify our collections by getting books that are printed outside of the global north, and outside of the Anglo-American capitals of New York, London, Paris and Germany?” Lannon asked.

If you visit Special Collections to view the new Wheatley acquisitions, you will be looking at more than just dusty pages, you will be looking at a literary history, and arguably, a literary future.

“There are so many issues in Wheatley’s writing that we’re still working with as a society,” Phillips said. “One of the exciting things about looking at Wheatley right now is that we’re waking up to how relevant she is in ways that weren’t really appreciated ten, fifteen years ago.”

For now, you can view these early Wheatley’s works by visiting Special Collections on the second floor of Skillman Library.