Susan Trotter considers herself a pioneer. Along with Joyce Cohen ‘74, an Easton native, she was the first woman to submit her enrollment deposit for Lafayette College – just three days after she was accepted – thereby becoming Lafayette’s first-ever female student in the spring of 1970.

“At the time my father said, ‘Women go to school to get their MRS,’” Trotter said, using a slang term for when a woman attends college to find a husband as opposed to earning an actual degree.

In a way, Trotter would go on to prove her father right as, just a year and a half after she stepped foot on College Hill – where she made a name for herself as one of the first female cheerleaders – she would drop out to marry her high school sweetheart, a decision that was a “heavy one” to make.

“But then I realized that women do not go to school to get their MRS,” she said. “They go to school to do some pretty terrific things — terrific and interesting things.”

Trotter would go on to complete her bachelor’s degree at Monmouth College, earn a master of business administration from Columbia University and become the first Connecticut woman to earn the coveted MAI designation from the Appraisal Institute.

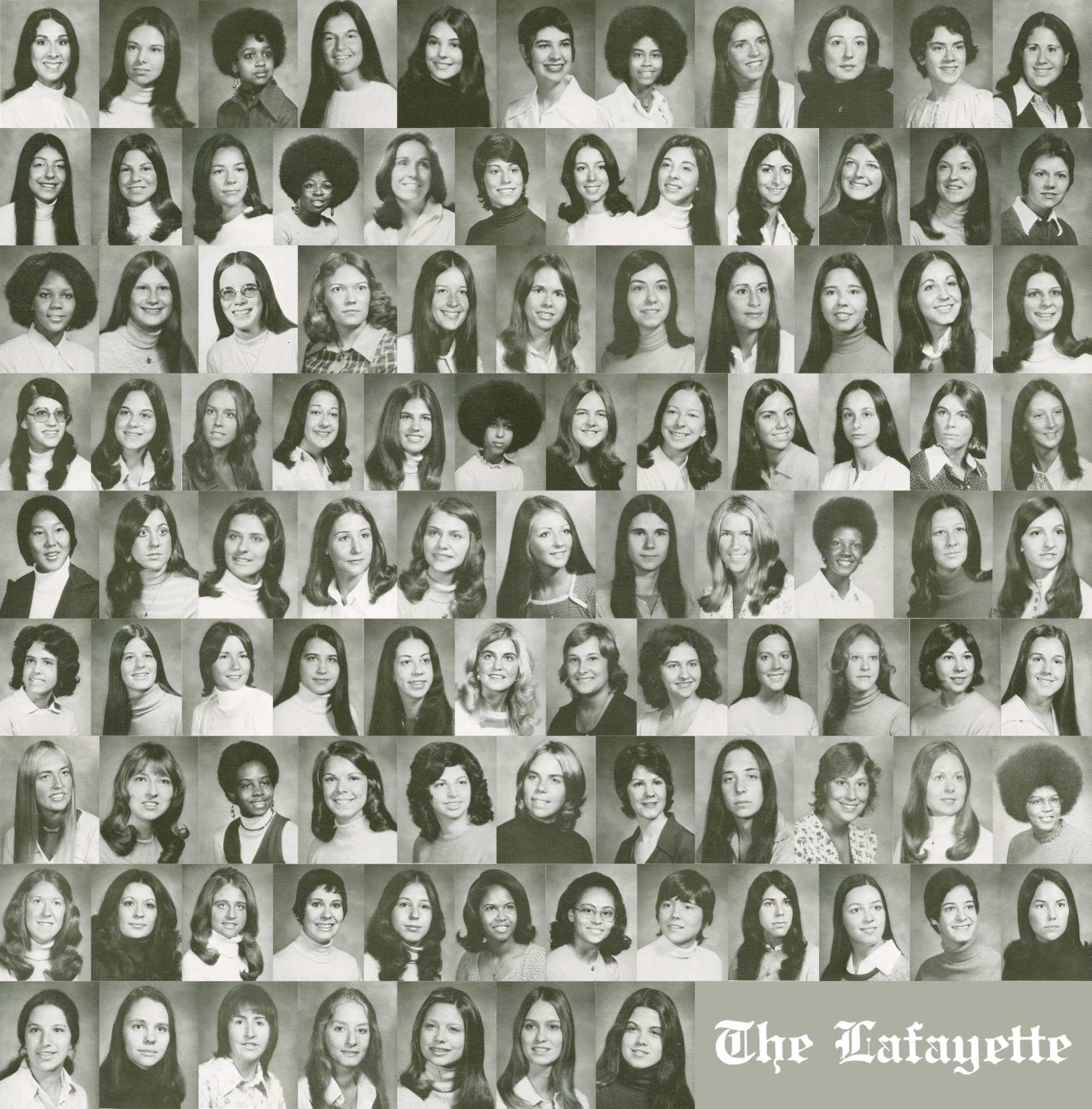

It was this trailblazing spirit that brought Trotter and around 130 other freshmen women to Lafayette in the fall of 1970. Some felt that the opportunity to be a pioneer was one they could not pass up. Some felt as if they had something to prove. Some, like Trotter, simply relished the challenge.

Over the past month, The Lafayette spoke with many of the women in the first fully co-ed class – the class of 1974 – with its 50th anniversary approaching. These are their stories.

“Okay, now what do you want?”

When Lafayette announced in 1969 that it would begin accepting women, Deborah Everett-Holley ‘74 saw an opportunity.

“I like doing things first — that’s kind of my personality,” Everett-Holley said. “Being denoted as the first to be able to do something was one of the draws.”

Christine Capone Sandy ‘74 was encouraged by a guidance counselor to join the first co-ed class.

“My guidance counselor said to me, ‘You know, Chris, you helped rewrite the student government constitution,’” Sandy said. “‘You like challenges. There’s some of these all-male schools that are going co-ed and maybe you’d like the challenge of being a pioneer.’”

But Alma Scott-Buczak ‘74 did not choose Lafayette to be the first – “I really came to Lafayette almost by accident,” she said.

“When I got to the campus, I thought it was the most beautiful place I’d ever seen on Earth,” said Scott-Buczak. “That’s how I decided to come to Lafayette. It wasn’t anything about being a pioneer in the first class of women.”

When Margaret Golieb Axelrod ‘74 arrived at New Dorm, the building now known as Ruef Hall that housed all of the incoming female students, she was taken aback by the sight of so many men.

“I was surprised my father allowed me out of the car because there were all these men standing there waiting to help you up with your bag so they can meet some of the girls,” she said.

While the men of Lafayette were excited about the women’s arrival, the facilities were not prepared mindfully. According to Liza Roos Lucy ‘74, roommates were assigned partially based on dress size, as the college believed the women would want to share clothes.

“I don’t think they really knew much what to do with us,” Roos Lucy said. “They took out two of the showers and put in bathtubs, because girls like tubs?”

Roos Lucy recalled that the campus doctor was unprepared to treat women.

“I had a car and on Tuesday nights I would ferry girls back and forth to Planned Parenthood at the hospital,” Roos Lucy said. “That became our doctor.”

Scott-Buczak recalled being unable to push open the heavy doors to enter Pardee Hall until a female student complained and the college replaced them.

“I’d have to get there early because I’d have to wait for somebody who could open the door so I could get into class,” she laughed.

This unreadiness for women was also evident in the athletic options available to women – there were none.

“We got there and then the school said, ‘Okay, now what do you want?’ Axelrod recalled. “So we said, ‘Well, we want a tennis team and we want to play flag football.’”

Those options trickled onto campus, though by the end of the women’s four years, the options were still limited. In the 1974 yearbook, each individual men’s sport was allotted a page of photographs, while all of the women’s sports together were granted just two pages.

“You had to prove that you were right”

Ann Huntington Barnett ‘74, who majored in math, believes that the female students had an academic edge over their male counterparts.

“I believe that the academics of the women who were accepted was probably a bit above the academics of the guys who are already there,” she said.

Despite this, Everett-Holley felt that women had to “do better than the best guy.”

“I don’t get the sense that the women were ever afraid to show how smart they were in a classroom,” Diane Vollweiler Elliott ‘74 said.

Everett-Holley, who is Black, recalled an instance of being second-guessed by a professor of African American history when she wrote a paper that discussed how the “separate but equal” laws in her home state of Virginia had been changed in name, but not in practice.

The professor gave her a failing grade.

Instead of accepting the grade, Everett-Holley sent her mom to the offices of her local newspaper to provide her with evidence of her hometown remaining segregated. Everett-Holley, for whom Lafayette was her first fully integrated educational setting, then set up a meeting with the dean who changed her grade.

“Depending on who the professor was, you had to prove that you were right when you were right,” she said.

“I vividly remember in one of my first classes a professor welcoming us by saying, ‘and welcome to the female students. This was the president’s desire and the board’s. It was not something that the faculty wanted,’” said Darlyne Bailey ‘74, who later became a Pepper Prize runner-up.

Not all students felt the same. Deborah Martz-Lysaght ‘74 recalled being treated with compassion in times of illness.

“I didn’t feel that there was any gender-based discrimination,” Martz-Lysaght said. “During my third year, I got ill, and they were so helpful in terms of being accommodating.”

But the old attitudes towards women prevailed from time to time.

“My economics advisor [asked] me what should I bother going to law school for. I should just get married and have children,” recalled Axelrod, who is now an attorney at a Manhattan law firm bearing her name.

Laura Bramnick ‘74 transferred to Lafayette from an all-women’s school in her junior year.

“I had a professor who I adored, who was an art professor from Bryn Mawr,” Bramnick said. “She said to me, ‘What are you doing here?’ She didn’t have a lot of respect for Lafayette. I just remember being kind of jolted. ‘You come from this place that’s so creative and this place is so stuffy.'”

“Double burden”

Bailey, Scott-Buczak and Everett-Holley faced a second set of issues as some of the first Black women at Lafayette.

“I had one of the young women who I liked instantly call me up when I was home and say ‘My mom isn’t gonna let me be a roommate of yours,’ and so that was my first real awareness of what overt racism felt like,” Bailey said. “We didn’t talk about microaggressions then, you knew there was something off sometimes.”

Bailey recalled being accosted by intoxicated white male students singing “Brown Sugar” by The Rolling Stones.

There was “a group of young white guys who are clearly inebriated, probably from beer and singing ‘Brown Sugar’ as I was walking across the campus and getting louder and making the space between them and me smaller and smaller, and as I walked up faster, they walked faster,” Bailey said. “That wouldn’t have happened to you unless you were a person of color.”

The “Brown Sugar” incident resulted in Black women being escorted by Black male students across campus to ensure they felt safe at all times.

“It was dealt with by the college, but some of the white students had never really been in schools and neighborhoods with students of color, and a lot of the guys, they knew there were women but they acted like this was the first time they’ve ever been with women,” Bailey said. “We had the double burden, and I would say blessing, being women and women of color.”

“I felt much more of a trailblazer as an African American student than I did as a woman,” Scott-Buczak said.

Finding a community

“I wasn’t an engineering student, I wasn’t a Republican and I wasn’t from New Jersey, so those three things made it very foreign to me,” said Patricia Soll ‘74, a self-professed hippie.

Soll and her hippie friends made their “own small community in a small school” in an off-campus house on Cattell Street.

“By this time I wasn’t getting stoned or anything, but everyone else was and it was just a very peaceful, beautiful place to live,” Soll said. “We all had dinner together, we used chopsticks so we didn’t have to clean silverware and we were more part of the community there.”

Many of the women found community in New Dorm – the older women who transferred to Lafayette in 1970 acted as resident advisors.

“I think that I kind of felt like we were a sorority, the few of us,” said Nancy Brennan ’74. “Everyone knew everyone and certainly, we didn’t all pal around all together, but there were plenty of groups of women that had very close relationships.”

In the fall of 1971, a team of women competed against Lehigh in a powderpuff football game — the “Leopardesses” emerged victorious.

“I remember catching the ball and running and just hearing all these people yelling and I was just grinning from ear to ear,” said Bailey who was a linebacker. When she got to the end zone, Bailey spiked the ball into the ground “as they do on TV” only to realize she was in the wrong end zone.

“What people were yelling was ‘Darlyne, you’re running the wrong way!’” she said. “But I didn’t hear them, I was just running so proudly.”

While the women found their own pockets of campus to call home, Lafayette’s social scene centered definitively around fraternities.

“The weekend was: you went to the football game or the basketball game, and then you went home and went out to the parties at the fraternities,” Scott-Buczak said.

Women largely relied upon fraternities for meals as, at the time, meal plans were largely based on fraternity affiliation.

“I loved eating at Phi Gam,” said Marilyn Balamaci ‘74 of the now-defunct Phi Gamma Delta fraternity. “It got a little wild but it was a great time and they had the best parties.”

But not all women wanted to eat at fraternities. For this, the college had a solution.

“They decided that the women would probably like to cook, so at each of the little common areas in the dorm, they built little kitchenettes,” Sandy said.

Looking back

Many of the women interviewed by The Lafayette agreed that being among the first helped shape them.

“The most important thing that happened at Lafayette in my mind is I was forced to be a woman – a young woman – in a man’s world,” Balamaci said.

These formative experiences brought a number of the women back to Lafayette. Scott-Buczak works in Lafayette’s human resources office while Brennan, Axelrod and June Sprigg Tooley ‘74 ended up serving as trustees.

“When I was a trustee and on campus regularly talking to the women, nobody ever had any idea that it wasn’t a co-ed school,” Axelrod said. “It was so far in the past historically that it didn’t even cross anyone’s mind and it didn’t affect them anyway, so it obviously worked.”

In 1981, Tooley, who currently works in the arts, was tapped to give a speech at commencement.

“I also felt kind of sorry for the students because sometimes there are big stars who come and I wasn’t a star,” Tooley said. “I was just a female graduate.”

Over the years there have been multiple efforts to commemorate the first women of Lafayette, ranging from an extensive oral history project to a a scholarship fund to a theater department production.

In 2014, Roos Lucy stitched together the “First Co-ed Quilt” out of old shirts, photographs and 1970s memorabilia submitted by the class of 1974.

A recent, ongoing dedication to the first co-eds is “Love Letters to Lafayette,” led by Brennan. The project aims to compile letters detailing the positive experiences the first Lafayette women had to be compiled into a book sent to all the women and Skillman Library.

“I just think if somebody’s going by and you see a book with a little case, and it says something about the first woman, once again, it tells you it’s a piece of history,” Brennan said.

The college recognizes the women of the class of 1974 as pioneers, a title with varying degrees of relatability.

“I think myself the first co-ed; ‘pioneer’s’ a little weird,” Roos Lucy said. “I’m not wearing a bonnet or going across the Great Plains or anything.”

Balamaci saw things differently.

“I didn’t want to go there to prove a point, but I knew that we would be special and this was a special time and if I could contribute to that and understand it, that would be great,” Balamaci said. “So yeah, we were pioneers.”

Elisabeth Seidel ’26 and Emma Sylvester ’25 contributed reporting.