Controversial app a hotbed for bullying

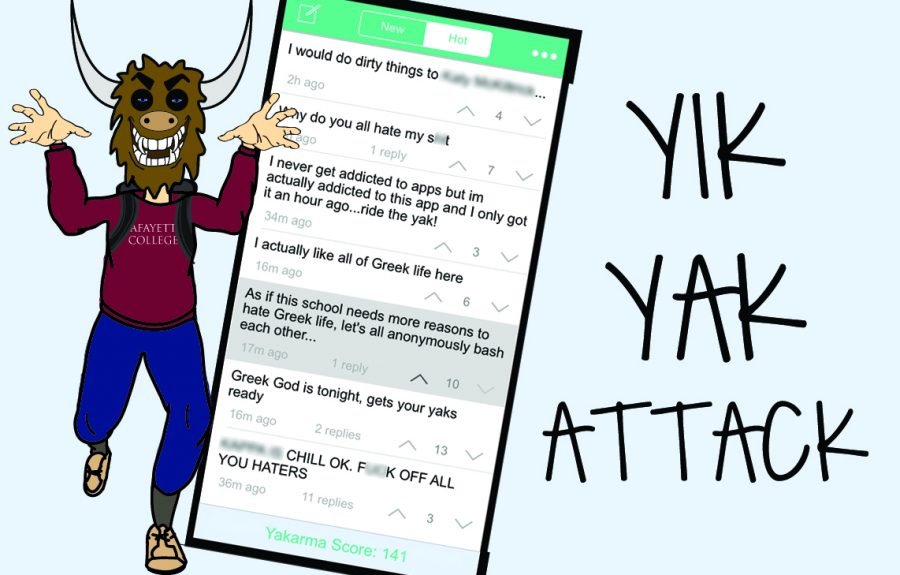

Illustration by Liz DiSabition ‘16

Lafayette students are now susceptible to Yak attacks.

No, not the hairy Himalayan bovid. Yik Yak is a new social media app that exploded at Lafayette last week, moving from five posts a day to multiple posts a minute. Unlike relatively harmless procrastination tools like Candy Crush and 2048, there is a certain degree of malevolence to the newest fad.

The best way to describe the app, created last fall by two Furman University graduates, is that it functions as an anonymous Twitter with a twist: you can only see posts, or “Yaks,” that have been posted within your immediate geographical area.

Once the app started seeing more activity, its primary use has been to insult and attack. The methods of the attacks range from the relatively harmless (“***** only drives Honda Fits”) to the homophobic (“Biggest fag in **** go!!!!” reads one) to those making light of rape (“ ‘No means yes’ –****” reads another) and anywhere in between. While such attacks, many of which constitute harassment, have declined since Yik Yak’s first ripples on campus, it still has a reputation as a bullying tool.

Yik Yak is a national phenomenon. Schools like Texas, Colgate, and Lehigh are feeling the effects the app. Lehigh Assistant Professor of Journalism and Communication Jeremy Littau first heard about Yik Yak at a conference and immediately began tracking the app’s activity at Lehigh in early January. He reported that it took off around the time Lehigh students returned from spring break, and that from what he’s seen, the app should be taken seriously.

“What’s particularly seductive about this technology is that it’s mobile,” Littau said. “We’ve seen other confession board-type sites that can be spammed because they’re on the web, whereas here with Yik Yak, it’s based on being in close proximity to a certain group of people. The ability to do damage to a community is pretty big at this point.”

Littau said that this summer will provide a good litmus test in regards to Yik Yak’s longevity, because most students will be off campus and therefore won’t have much desire to use the app. Assistant Professor of English Tim Laquintano, who specializes in writing technologies and digital media, perceives Yik Yak as a “flash in the pan” and doesn’t foresee much long-term use.

“My initial thought was that the volume on there isn’t sustainable,” he said. “It’s probably going to be a relatively short-lived fad.”

Laquintano also cautions users that although the app promotes short-term anonymity, nothing in the digital age is truly anonymous.

“There is no anonymity,” he said. “Presumably, [the app is] keeping track of IP addresses. If the various messages led to some serious offline consequences, most of the time they could chase it back.”

Both professors agree that there’s very little that school administrations can do to halt the use and spread of the app. Even if administrators deleted the app from the WiFi network, students can access it from 3G devices. It’s even risky to speak out against it, Laquintano said.

“It’s a really difficult thing to respond to,” he said. “Straight up, some of that stuff constitutes harassment, so I would expect there to be some sort of response. How effective that would be, I have no idea. And then how much of that feed will be about administrative response too?”

Both Laquintano and Littau stated that the amount of posts is not indicative of the entire campus, that only a small percentage of students are posting. Littau’s March 24 blog post cites a “90/5 principle—90 percent of the content is created by less than 5 percent of active viewers.” Both professors said the popularity of the app is most likely fueled by the Fear of Missing Out, popularly referred to as “FOMO.”

But Yik Yak has lasting effects, particularly in the oft-discussed Greek community. When the app first took off last weekend, Greek organizations and their members were the primary targets of degradation. The intimacy, detail and locations of the Yaks suggest that the propagators of the Greek-centered Tweets are fellow Greeks spurring old rivalries. Another Yak from Tuesday suggests as much: “As if this school needs more reasons to hate Greek life, let’s all anonymously bash each other….”

Littau said that Greek organizations at Lehigh were also the first generators of content, and eventually fraternities and sororities ordered their members to delete the app. Some organizations at Lafayette have already followed suit, condemning Yik Yak and strongly encouraging that members remove the app from their devices or refrain from posting.

“[The Interfraternity Council] strongly encourages the Greek community to immediately delete the application and cut it off completely as it is not a fair representation of our community,” IFC President Nate Diaz ‘15 wrote in a prepared statement. “We value our place and role on this campus and participating in any sort of behavior like this is not consistent with that value.”

Director of Fraternities and Sororities Dan Ayala declined comment.

The app also affects prospective students. Although designed with college students in mind, Yik Yak first gained ground in grades K-12. With tours picking up right as the weather gets warmer and Yik Yak picks up at Lafayette, students are likely to use the app to get a feed of information.

President Alison Byerly hopes that the quality of the Lafayette student’s character will prove to be stronger than the harmful posts of the few.

“I know that Yik Yak has hit a number of other local campuses, including Lehigh, and has not been helpful to those communities,” she wrote in an email. “I would like to think Lafayette students could see this as an opportunity to do better.”