Many students spent their spring breaks trying their damndest to get away from Easton. We had a different idea.

Over the course of 11 days and 4,750 miles in a four-seater Cessna airplane, we visited every single incorporated Easton in the United States – all 13 of them – and a few others to boot.

We were joined by Remy Oktay ‘24, Lafayette College’s ambitious resident pilot and, later, former editor-in-chief Lucie Lagodich ‘22, with an assist from news editor Selma O’Malley ‘26. Along the way, we met with townspeople, historians and local government officials, toting a Lafayette College pennant to be signed by each Easton mayor or mayor equivalent.

But why? Do we just love sleeping in Super 8 hotels and going days without eating a vegetable? No. This journey seeks to get at something more: learning what it means to be an Eastonian (or Eastonite or Eastoner or whatever).

This 14-state journey brought us to some of America’s remote reaches, wealthy suburbs steeped in history and many, many tiny farm towns that are only getting smaller. But despite the differences between these places, what we found was a common hospitality we thought only existed in folklore. It made us think twice about our closed-off, Northeasterner nature.

Below is a tour of these towns that happen to share a name with the city we call home. Buckle in, folks. It is time to take flight.

Day 1 (March 8): Easton, Illinois

- Founded: 1873

- Population: 312

- Named for: Havana, Illinois postmaster Oliver C. Easton

“Don’t drive too fast, you’ll miss it.”

That is what the Logan County Airport manager had to say of Easton, Illinois as he handed us the keys to a 2005 Dodge Caravan, a vehicle that certainly could not top 80 miles per hour. But we took it slow nonetheless, not in the least because the minivan had mushy breaks and a windshield wiper that flew off mid-rainstorm.

Our first stop was at Village Hall where we met Village President Don Mustered III in his humble wood-paneled office, a space seemingly frozen in time. Two calendars in the office suggested the date was either April 2021 or January 2011. There was also a stove in the office, but Mustered had no clue if it worked.

Mustered was raised in Easton. His mother tended bar and his father worked the village grain elevator. He hadn’t heard the word “Eastonian” in a while.

“A little dot in the road is what we are,” Mustered said with a slight country drawl. He was elected to office by winning all 27 of the votes cast.

Mustered spoke warmly of the Easton of his youth, describing it as “a busy little town” with a railroad running through it. Today, the railroad is no longer and half of the buildings on Easton’s main street have disappeared.

“I wish it was back to that busy little town,” he said, wistfully.

Mustered drove us around the village in his pickup truck and pointed out signs of revitalization: a new basketball court, new lighting and plans for a pickleball court and expanded park programming. But the downturn elsewhere was evident, and he and many of the townspeople we spoke to blamed the consolidation of schools and other services for the village’s decline.

Joann Lynn of the Mason County Genealogical and Historical Society noted that big box stores and online marketplaces suffocated small businesses, while a nearby coal plant that employed 75 people was shuttered in 2019. These developments, according to Lynn, drove people away.

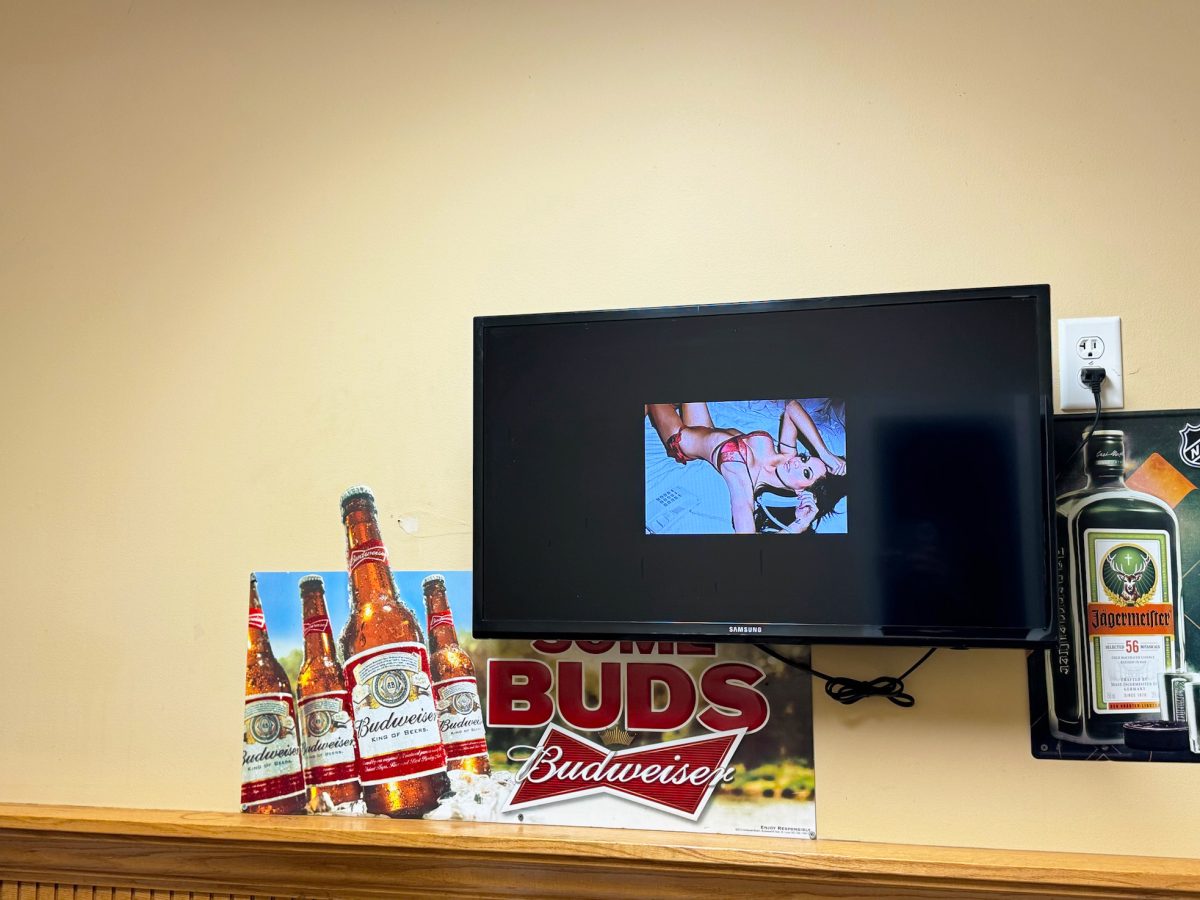

But if this town were in decline, we certainly could not tell when we made the short walk to Tom’s Tap & Grill, Easton’s only restaurant. The WiFi password was “NattyLite.” The men’s restroom had a television displaying a slideshow of scantily clad women.

The restaurant was packed. The waitress, who was also the bartender, kept interactions short as she buzzed between patrons and the kitchen. But when she had a second to spare, we told her of our journey. Almost instantly, everyone in the bar knew.

We were quickly introduced to Jan and Janel Hickle, a mother-daughter duo whom we asked about the Eastonian demonym. Jan Hickle quickly corrected us to “Eastonite;” others at the table agreed.

Jan Hickle told us she was a lifelong Easton resident whose father had laid the village’s telephone wire in just three days after a 1968 tornado. Like Mustered, she recalled the town having seen better days.

“All we have now is a bank, a bar and a post office,” she said.

But the pride in the village was evident. One resident went home to grab us roughly a metric ton of purple and gold Easton merchandise.

“Suck it, other Eastons!” shouted one patron as we left the bar.

Day 2 (March 9): Easton, Kansas and Easton, Missouri

- Founded: 1854 (Kansas and Missouri)

- Population: 213 (Kansas); 227 (Missouri)

- Named for: Kansas Gov. Andrew Reeder of Easton, Pennsylvania (Kansas); Being east of St. Joseph, Missouri, maybe (Missouri)

To get to Easton, Kansas, one must drive down 20 minutes’ worth of gravel roads. Eventually, these roads lead to the town’s paved main street, where we found Easton Cafe.

Donna, the owner and only employee of the restaurant aside from the cook sat down at the only other customer’s table and took our orders, teasing Remy for his many allergies (which she and the cook took great lengths to accommodate).

Mayor Phillip Mires, in Carhartt and a cowboy hat, joined us for lunch a few minutes after we ordered. He had been at Ned Recks Bar & Grill down the street, having a couple of Budweisers. Donna gave him a hard time about not bringing her a beer.

Much like his Illinois counterpart, Mires told of a town in decline, in large part because of two “500-year floods” having occurred in the past two decades.

Mires, a reluctant mayor, has retained the job in part because the townspeople keep writing him in and in part because he wants to put Easton “back on the map.”

“I live here,” he said. “I don’t want to see this town go under.”

Mires told us he hoped the abandoned, overgrown grade school at the edge of town would be knocked down and replaced with a Dollar General. He said it would bring money and jobs to Easton.

After lunch, Mires joined us in our rental car for a guided tour of the town. He first directed us to his house so he could pick up the keys to City Hall. His house, conspicuously, appeared to have been torched.

Mires informed us that he had accidentally set fire to a large portion of the home when a lithium battery in one of his solar panels exploded. He was still living there but was waiting for spring to take the roof off and replace it.

Our tour continued with a walkthrough of the old firehouse, a former jail now used for storage. The restrooms, previously cells, had foot-thick walls, which Mires demonstrated by repeatedly pounding the ceiling.

We wrapped up at City Hall, where a large domesticated goose across the street hissed at us menacingly. Inside, a massive, shiny vault door revealed the building’s previous life as a bank. The vault is now also used for storage.

Mires could not find any souvenirs to give us, but he promised he would look around with Becky Jones, the city clerk, for something to send through the mail. He eyed a large, decommissioned “Easton” street sign.

“Maybe I’ll send you that,” he said.

* * * * *

It was well past sunset by the time we reached Easton, Missouri, but the night was young at its only restaurant, Easton’s Pub & Grub.

The bar was bustling – it was Ladies’ Night. We followed Mayor Michael Kerns and Lori Caylor, the city clerk, to a table in the back where Caylor’s mother, sister and husband were already seated. Behind the table hung a sign that read, “God loves farmers.”

Kerns, at just 28 years old, has been Easton’s mayor for three years. He collects a $50 monthly mayoral salary, though he wasn’t even aware the job was paid until the checks started coming. When he assumed office, he received a letter from the Missouri government saying he was a year too young to be mayor. Kerns ignored the letter.

In addition to being mayor, Kerns is the water commissioner, assistant fire chief, fire protection district captain, park board president and a member of the board of the local senior home. He also works as a machinist at his dad’s machine shop and runs a lawn care business.

We asked Kerns if he ever had any free time. He does not.

Kerns ordered a tenderloin salad (no onions) from the quarter-page tenderloin section of the two-page menu. He waited respectfully for everyone to get their food before he began to eat.

Over our dimly lit meal, he explained that the town was once known as a hot spot for illegal drag racing. Today, only one part-time cop is needed.

“It’s just gotten slower,” explained Caylor, whom Kerns consistently relied upon to fill in the blanks when he answered questions.

For a town with, quite possibly, more stray cats than people, there were myriad sights to see after dinner, such as the water tower bought for $1 and the park, home to the annual car show established by Kerns himself.

The tour ended at the firehouse, which was seemingly brand new. The fire department had relocated there from a ridiculously small building that had “scrape marks down both walls” from the three trucks it once housed. Such marks were plainly visible on the old fire truck parked outside of the new location.

Day 3 (March 10): Easton, Texas

- Founded: 1835 (as Walling’s Ferry)

- Population: 499

- Named for: Unknown

We rolled into Easton in an obnoxious white Mercedes-Benz loaned to us by the airport. Two children waved long sticks at us as we photographed the city limit sign.

Ashamed of our Mercedes, we stashed it in a church parking lot across the train tracks and traversed Easton on foot. We happened upon Patrick Starling, who was outside his home with his son and daughter-in-law who were washing one of their two dogs with dish soap.

Starling pointed at every house in our vicinity and identified their occupants as a cousin, aunt or uncle of his. He told us of Easton’s Heritage Turnip Green Festival, one of the city’s main draws. The next town over, he said, holds an annual syrup festival.

He then directed us to the mayor’s house. On the way, maybe a dozen pickup trucks passed by, carting ATVs to a nearby off-roading trail. None of the off-roaders seemed to be from town.

The mayor, Walter Dale Ward, was not home. His wife was, however. She said her husband was away at work “in the mines.”

On our way back to the Mercedes, we stopped to chat with a group of men sitting in folding chairs in the shade of a large, droopy tree. Dominoes were set up, but nobody was playing. The men immediately identified us as tourists.

“Did your four-wheeler break down?” one of them asked us. We explained our trek to him. A second man then introduced himself.

“I’m the junk man,” he said. “Do you have any junk?”

We had no junk, we responded. We then asked the junk man if Sunday afternoons in Easton were always so quiet – we saw more dogs relaxing in the sun than people.

“It’s always like this,” replied the junk man.

Day 4 (March 11): Easton, Minnesota and Easton, Wisconsin (Marathon County)

- Founded: 1873 (Minnesota); 1861 (Wisconsin)

- Population: 177 (Minnesota); 1,148 (Wisconsin)

- Named for: Founder James C. Easton (Minnesota); Unknown (Wisconsin)

The day started with a meeting at the Faribault County Register, the local newspaper – the trip’s benefactor had asked that we do some media engagements. The Register’s editor, Chuck Hunt, informed us that we had scheduled our trip a week early as we would be missing the St. Patrick’s Day parade, which he told us was the largest in the county. The punchline? It is the only such parade in the county. It is two blocks long.

Minutes later, Kevin Mertens, a staff writer for the Register, entered Hunt’s office. He too said that we were a week early as we would be missing the largest St. Patrick’s Day parade in Faribault County, as would several others throughout the day.

Mertens, an Easton-area farmer, took it upon himself to be our tour guide for the day, carting us around Easton in a minivan he never locked while in town. On the drive to Easton, Mertens noted the steeple of the town’s Catholic church, visible from miles away. It was recently rebuilt after being toppled in a storm.

“The Catholics help out the Lutherans and the Lutherans help out the Catholics,” Mertens said of the cleanup effort.

A short drive from the church is the city office, where we met Rose Doyle, the city clerk who also operates the town gas station. She explained that Easton has grown since the pandemic due to remote workers.

“For a small town, we have a lot going on,” she said, noting the butcher, a diesel engine mechanic and a bridal shop that draws patrons from as far as Minneapolis. “Every house is full.”

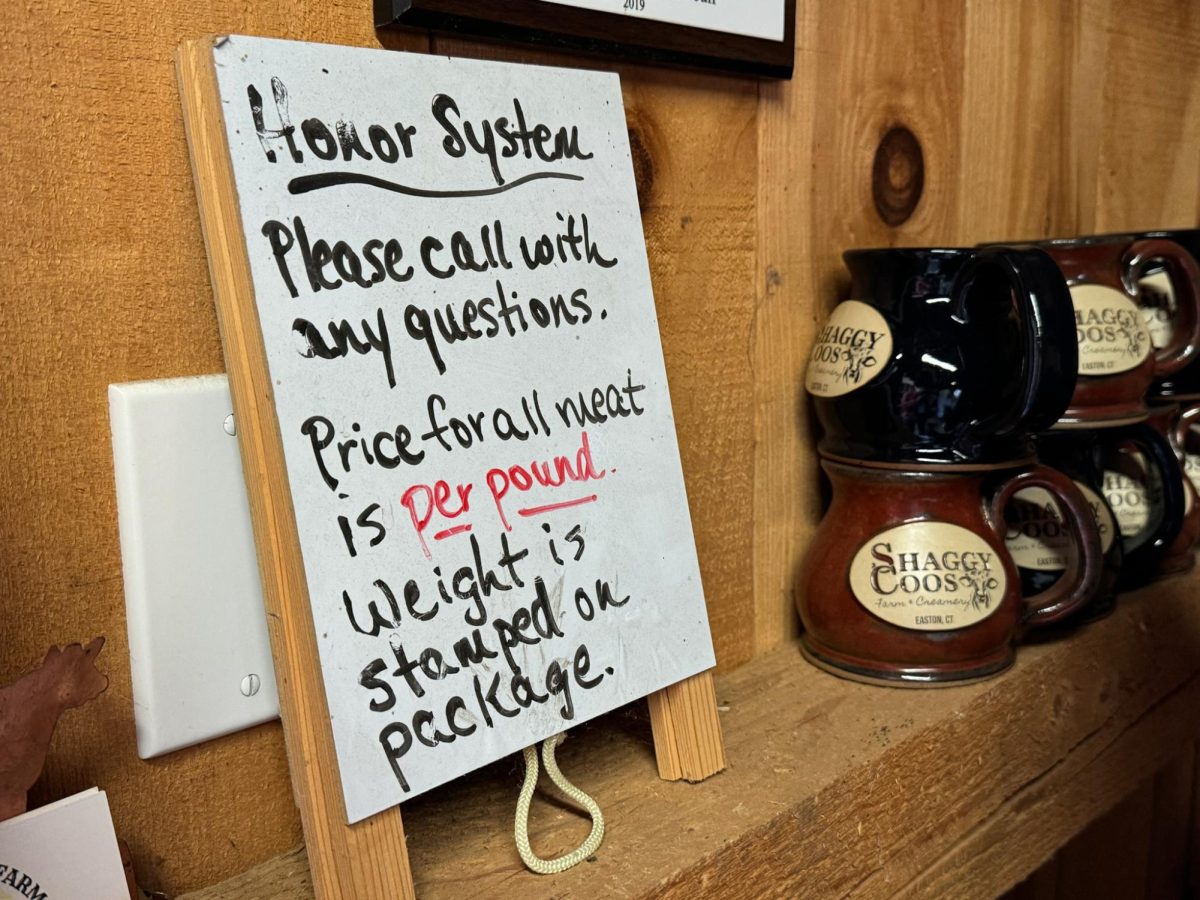

After a rendezvous in Margaret’s Pub, an Irish-themed establishment that formerly housed the town hardware store, it was onto Country Butcher Shop.

Joel Sonnek, who took over the shop with his brother after his father died, came out from the back to speak to us. His rough grey apron, patched with denim, was stained pink in the front. His mom has been cutting Mertens’ hair “for 40 years.”

Sonnek opened one of the shop’s freezers and started passing us 1-pound slabs of his famous “Snack Sticks.” Given the plane’s weight limitations and our desire to not fall out of the sky, we opted to only take two packs of sticks. We’d unfortunately forget them in a Wisconsin hotel mini-fridge.

* * * * *

We arrived in Easton, Wisconsin with only enough time for dinner. Our requirements for a place to eat were lax: there must be Eastonians to chat with and there must be cheese curds on the menu for Trebor, a cheese curd virgin who had been saving himself for Wisconsin.

Corral on 52 checked those boxes.

The parking lot of the bar was painted pink by a suspiciously familiar “corral” sign. The bar owners confirmed that the sign had been ripped from a shuttered Golden Corral.

Corral on 52’s ceiling was covered with Sharpied messages and signatures. The wood-paneled walls were dense with crude tin signage. Hits include: “Low-cut blouses are looked down upon in this establishment” and several signs warning patrons to not “finger the hole” of the bottom-filled beer glasses.

The bar was appropriately empty for a Monday night in rural Wisconsin. The six people inside, three of whom lived in Easton, regarded us with a healthy dose of skepticism until we explained our plot. This sparked a debate between the patrons as to whether or not we were actually in Easton. It was decided that we were. Thank God.

We designated the woman to our right the mayor for pennant-signing purposes. A woman to our left, Renee, was in disbelief that Remy was the pilot, insisting that we had taken a “little car” or a bus across the country. She was also adamant that the “catfish special” we had eaten in Illinois had really been bottom-feeder carp. None of us would order catfish for the rest of the trip.

The bartender, Scott Leitza, played dice and took shots with Renee and her husband. Leitza wore a grey t-shirt that read “Eat cheese from Wisconsin.” The dice cup was modeled after a block of cheddar. He and the bar patrons educated us about what made a good cheese curd.

Cheese is not Easton’s only asset.

“There’s gold out there in the town of Easton,” said Renee. A man sitting at a computer monitor behind the bar corroborated this and showed Remy the positive results of his land’s gold inspection. He said that a company pays him a certain sum each month to retain buying rights to the land.

After we had eaten our food, we asked Leitza if he might have some Easton keepsakes. He produced a handful of little Corral on 52 magnets and then disappeared. He emerged seven minutes later and planted a small cup of googly eyes and a rickety, roughly foot-tall wooden sculpture on the bar.

“Here,” he said. “This is what I’ve got.”

With its two legs and maybe ribs, the sculpture seemed like an abstract interpretation of the bottom half of a human. We asked Leitza what we should name it.

“Josie,” he replied without hesitation.

Leitza then instructed Trebor to glue a single red googly eye to a part of Josie that could best be described as her head.

As we were leaving the bar, a man who identified himself as Dave “with one V” stood up and told us that he wanted to support our journey. He then pressed a folded $100 bill into Remy’s palm, closing Remy’s fingers over the money and pushing his hand to his chest. Remy tried to decline.

“No, no, no,” Dave with one V said. “You need to take this, your next meal is on me.”

This man was far too emphatic. Remy had no choice but to accept the money.

Day 5 (March 12): Easton, Wisconsin (Adams County) and Easton, Michigan

- Founded: Unknown (Wisconsin); 1843 (Michigan)

- Population: 1,062 (Wisconsin); 3,058 (Michigan)

- Named for: Unknown (Wisconsin and Michigan)

The second Easton, Wisconsin, two hours south of the first, had just as many living souls as the local cemetery.

We checked out Town Hall for signs of life. Nada. But the poster-laden shed across the street spoke to us.

“Biden lied – Obama spied, under Secretary Hillary – Americans died, Trump is the only one on America’s side,” read one particularly poetic banner.

After searching in vain for human beings, a used car dealership appeared: Easton Motors. There we met car salesman Matt Gierloff, who did not know anything about the town he worked in.

“I’ve always said the town of Easton is named after us, which probably isn’t a great thing to say to a local,” Gierloff said.

To find Easton natives, Gierloff suggested we check out the gas station a few miles down the road, though he was not sure if it was in Easton.

Fortunately, his tip was rock solid. It was at The Corner Pump convenience store where we met our first and last Eastonian.

Ginger Bautista, whose first name matched her hair, worked the sandwich counter. As she smeared mayonnaise across a roll, she told us that she had moved to Easton after a divorce simply because she could afford it.

We asked if she wouldn’t mind signing our pennant as the honorary mayor, to which her coworker at the register (not an Eastonian) loudly exclaimed, “The mayor! That’s your new name.”

* * * * *

We were an hour late to the Easton Township budget workshop, but it seemed the people of Easton, Michigan had forgotten about it as well – 10 metal folding chairs set up for the people to observe their government in action sat vacant.

Over a plate of nachos later in the evening, the township supervisor, Bill Patton, put a positive spin on the lack of engagement.

“I like apathy,” he said. “Apathy tells me things are going good.”

Patton wore an Easton Red Rovers shirt under a green flannel. He explained that he picked the shirt up from an Easton, Pennsylvania Walgreens. The bulldog mascot matches that of Ionia High School a town over.

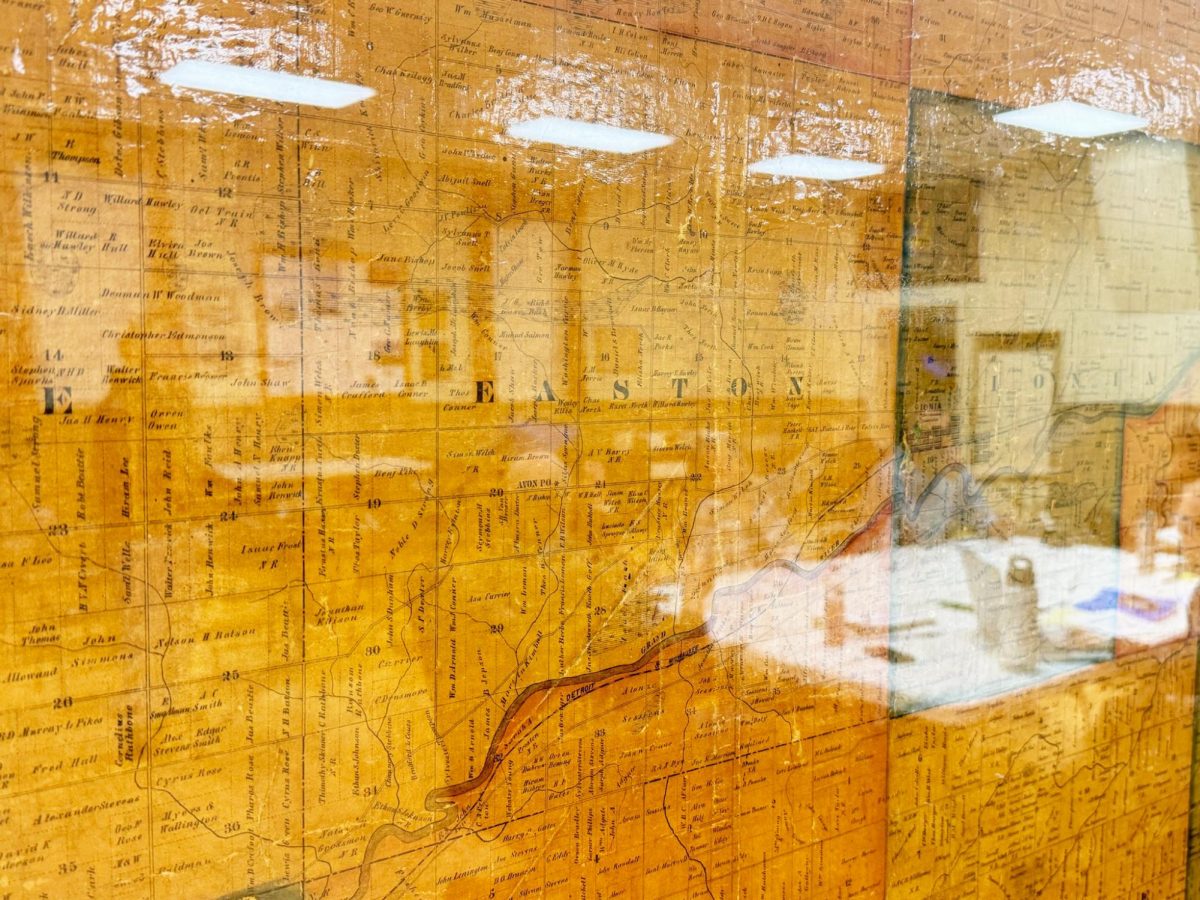

The workshop was a mundane but informal affair that took place in Township Hall. Breanne Rowley, the 27-year-old township clerk with a seemingly encyclopedic knowledge of local government, rattled through a laundry list of budget items: cemetery burial fees, marijuana sales, revenue from the three nearby state prisons. A large, yellowed map of Ionia County hung on the wall.

Most of the county’s townships are square plots. Easton is not – a river runs through the southeast corner. Because Easton had no bridge crossing the river when the boundaries were drawn, the township to its south got the land on the other side.

“We call that occupied Easton,” Patton said.

Easton Township’s biggest moneymaker is the three nearby state prisons, but the newest industry in town is marijuana.

After medical marijuana was legalized in Michigan in 2008, a businessman approached the township, which today votes overwhelmingly Republican, looking to open a dispensary.

“We said no,” said Patton, himself a Republican. “Years later, Michigan had a vote on recreational marijuana. We looked at the vote in our township and it was 60-40 in favor. The guy came back and we said, ‘Okay! We were on the wrong side of this issue.’”

Somewhere in there lies a metaphor for apathy.

Day 6 (March 13): Easton, Connecticut

- Founded: 1845

- Population: 7,605

- Named for: Being east of Weston, Connecticut

At last, we were back on the East Coast! After scooping up Lucie during a pitstop in New York, we gunned it to Easton, Connecticut.

Easton is a largely wooded town of farms and cows. Debbie Szegedi, the town clerk whose black business attire and pinstripe pants contrasted the rural backdrop, emphasized that Easton was growing because “people want quiet, people want more land.”

Paco Acosta, the cheery Easton Police Department dispatcher, reported that many of the calls the department receives stem not from crime, but from locals complaining about traffic during Christmastime in the “Christmas Tree Capital of Connecticut.”

“I want to scream at them, ‘Hello! We’re in Easton!’” said Acosta, an Eastonite of 24 years. “‘Haven’t you figured this out by now?’”

Three things keep Acosta in Easton: its “crazy history” (he said Easton’s many rock walls were built of the stones early settlers would hit while tilling the land), the scenery (namely the “beautiful vistas”) and the people (who often stop by the department “just to say hello”). Mary, the sole employee of the Easton post office, agreed with that latter point.

“Here, people are laid back,” she said.

Nowhere was this lax attitude more evident than in the hut that houses the town’s gas station/antique shop, adjacent to the post office that shares a roof with the cafe. When we entered, the two men sitting in comically short chairs hardly flinched. Given that we were in a gas station/antique shop, we peppered them with questions.

Do you have any favorite items?

“I don’t have any favorites,” said the gas station clerk/antiques salesman. “I don’t get involved with any of the stuff. I just sell it.”

What do you like about Easton?

“Nothing.”

Okay.

After this experience, we followed a tip from Acosta to visit one of Easton’s reservoirs, catching it just as the sun began to set. On the hike there we encountered a fallen tree dangerously close to taking out a power line; Remy immediately reported this to our new dispatcher friend.

Day 7 (March 14): Easton, Massachusetts

- Founded: 1725

- Population: 25,058

- Named for: Being east of Norton, Massachusetts, maybe

Easton, Massachusetts is the only other Easton that is home to a college: Stonehill College. That college is home to 783 Ames shovels stored on retrofitted library shelves.

Nicole Casper, a 1995 graduate of Stonehill College and its director of archives and historical collections, gave us a tour of the Ames shovels … and the Ames potato scoops and the Ames shovel-pickaxe hybrid and the Ames entrenching tools used by the military. Easton is known as “Shovel Town,” though it could easily be named Amesville due to the sheer number of buildings bearing the shovel dynasty’s name.

Stonehill was built on Ames cattle land, and the town library was endowed by the Ames family. The nearby Borderlands State Park, a destination for major motion picture shoots, was Ames land until 1971. Five Easton buildings were designed by the famed architect H. H. Richardson and draw architecture students from around the country – all of them were commissioned by the Ames family.

Even the town hall was an Ames mansion once upon a time, and it is at that wooded estate that we met Sean Dugan, the assistant town administrator, in an office that was once part of the servants’ quarters.

Dugan detailed Easton’s open town meeting form of government, which is common in New England but virtually nonexistent elsewhere. Any of Easton’s 17,000 registered voters may vote on matters like the town’s budget and zoning, though Dugan said only between 100 and 200 people show up to the annual town meeting, held in May. Despite this, Dugan calls open town meetings “the purest form of democracy in the country.”

“It’s a community that is very proud of its roots,” he said.

Easton has changed greatly over its 299-year existence. Home values have shot up, according to Dugan, but Mary Silva, an Easton resident of 35 years who heads the circulation desk at Ames Free Library, said that Easton has made an effort to be liveable, especially for senior citizens.

Silva said “the population’s commitment to keeping the community diverse and as green as possible” was her favorite thing about Easton.

Day 8 (March 15): Easton, California (by Selma O’Malley ’26) and Easton, Maine

- Founded: 1881 (California); 1865 (Maine)

- Population: 1,972 (California); 1,320 (Maine)

- Named for: Unknown (California); “Lying on both the eastern line of Aroostook County and Maine” (Maine)

Every time I texted a friend that I was visiting “Easton, CA,” over spring break, they (naturally) misread it as “Easton, PA.” This was typically followed by some confusion about how I would get there in three hours by car.

Easton is as flat as the rest of California’s Central Valley, a green suburb surrounded by acres of ochre ranches and vineyards. Roosters crowed in peoples’ backyards. The only encroachments on the sky were palm trees and the snow-capped Sierras on the horizon.

The first stops were two out of Easton’s three gas stations because the first had a bathroom “like a horror movie,” according to my dad and Easton-venturing partner. At the second, I met Erica, a 19-year-old gas station employee who had grown up in Easton.

Easton is “a very friendly town” of ranchers, according to Erica, who attended its elementary school (down the street from the gas station), middle school (across the street from the elementary school) and high school (across the intersection from the gas station).

After exploring the high school, we were directed by its administrators to L.B.’s Pit Stop to find locals.

Inside L.B.’s, a small but charming diner that is not to be confused with the nearby L.D.’s County Kitchen, patrons stared at us until disappeared to a table around a corner. An old Seahawks game was playing on the television behind us. We were apparently far enough away from San Francisco to be out of 49ers territory.

There was one waitress clocked in: Alex, from Fresno. I ordered a black-peppered turkey sandwich so stuffed with meat that I could only eat half. My dad ordered a coffee (“worse than United”) and a steak sandwich (“the stuff”).

L.B.’s regular characters began to shuffle in around noon. Alex dashed around the diner, greeting them and distributing take-out orders. She introduced us to “Uncle Larry,” an elderly man who sat across from our table at the bar and had lived in Easton all his life.

I explained the trip to Larry, who then called over his long-time friend, Susanne. I explained the trip to Susanne, who then called over her long-time friend, Debbie. I explained the trip to Debbie, and the three became my Easton informants.

“A farming community!” Susanne exclaimed when I asked how Easton could be described. She considers herself an “outsider,” having lived there for 45 years. Susanne came to Easton after marrying a fifth-generation Easton farmer.

“I never wanted to leave,” she said. When her husband died, her neighbors covered some of the funeral fees, and “everyone” was there.

I asked if anything had changed about Easton over the years.

“No!” the three said in unison.

Larry and Susanne agreed on the Eastonite demonym. Larry had heard of Easton, Pennsylvania, from friends who had been to the East Coast.

Susanne also tried to introduce us to several other locals on her way out, managing to slip in a derogatory term for Portuguese people. My dad said that we would be the talk of the town by the end of the day.

* * * * *

Hotel after hotel after hotel. They all started blending together. It was in a Best Western Plus in Bridgeport, Connecticut that Remy hatched the idea to go the Airbnb route in Maine.

Enter the Easton yurt.

For the uninitiated, a yurt is a portable circular structure historically used by the nomadic peoples of Mongolia. The Easton yurt is no glorified tent, however – it is a lifestyle, outfitted with a wood stove tended to by Traci, the gracious Airbnb host who also leads outdoor classes for local school children. The guestbook was filled with entries lauding the yurt and the Easton wilderness as life-changing.

The yurt happens to be 500 feet from the Canadian border, which is really just unguarded trees, but for legal reasons, we cannot confirm nor deny if we ever crossed it.

“I can throw a rock and hit someone in Canada,” said Jim Gardner, Easton’s town manager of 13 years who lives down the road from Traci. He told us that much of Easton’s early population was Canadian immigrants, mostly Catholics, and that the townspeople remember a time when they could visit their families in Canada without any restrictions.

None of Easton’s five churches are Catholic. A $6 million border crossing now formally separates Easton from the Canadian town of Wicklow.

Gardner grew up in Easton’s potato fields, making 25 cents for every 160-pound bag of spuds he produced.

But what about Idaho potatoes? Gardner and the other people in the town office were befuddled by this inquiry; they only know Maine potatoes (pronounced “puh-DAY-does”).

“That’s the only reason we’re here,” said Reid Clark, an Aroostook County deputy sheriff who had stopped by the office with his baby. “The plants.”

Industry, namely McCain Foods (potatoes) and Huber Engineered Woods (lumber), makes up 76 percent of Easton’s tax base, according to Gardner. Another integral part of Easton’s economy is snow, or as Gardner calls it, “white gold.” With the snow comes ice fishing, dog sledding and snowmobiling.

Gardner took us on a tour of the town, showing us the potato and lumber factories and Easton’s large Amish community, roughly 15 percent of the town’s population by Gardner’s estimate. He waved at an Amish man named Yuri who was walking by with his son.

“I don’t care what your name is, what you look like or where you’re from,” Gardner said. “We are one.”

Day 9 (March 16): Easton, New Hampshire

- Founded: 1876

- Population: 292

- Named for: Originally being the eastern portion of Landaff, New Hampshire

For two hours we lounged on the tarmac of Dean Memorial Airport without any means of getting to Easton, polishing off some Timbits and watching as Remy unsuccessfully attempted to hitchhike. Then our ride from Dave’s Taxi finally arrived.

We made for a sparse crowd in Dave’s Taxi, which ended up being a 14-seat minivan driven by Alan, a man with weathered skin and a shaggy gray mullet. We explained our gambit to Alan, with whom we were allowed two hours by the taxi company. Unphased, he called our journey a “magical mystery tour.”

First stop: Town Hall, which is unfortunately only open for three hours each Thursday. And like Town Hall, the porch and front yard of every home we passed on that mild Saturday was barren.

According to one of the town’s selectmen, two-thirds of the town’s land is trees. Go figure.

We made a quick stop in the neighboring town of Franconia to visit Lafayette Regional School, an elementary school named for the mountain looming over it. Earlier that week, a woman from the school’s main office recommended we stop in so someone could “point out the mountain,” which is fabled to produce a bold white cross of snow each spring. Given the nature of a school on a Saturday, however, we were forced to locate the largest object on the horizon without any help at all.

At our wits’ end, we sent Remy and Lucie to scout out a bed and breakfast to find literally anyone from Easton. They returned with a cryptic directive to find a red house with a red barn about a mile down the road, supposedly the home of Bob Thibault, one of the town selectmen.

But this lead turned up dry. Despite several cars in the driveway and a dog that barked each time we rang the doorbell, no selectman or relatives thereof emerged. Thibault would call us days later to say he had seen us on his door camera.

We saw Easton’s first sign of life on the way back to the airport: a woman walking into her home. We asked Alan to turn the van around.

Remy and Lucie asked the woman, Betty, what her favorite thing about Easton was. She said nothing and motioned toward the mountain.

Day 10 (March 17): Easton, New York and Easton, Maryland

- Founded: 1789 (New York); 1710 as Talbot Court House (Maryland)

- Population: 2,279 (New York); 17,101 (Maryland)

- Named for: “Being the eastern town in Saratoga Patent” (New York); Being like the capital of the east, possibly (Maryland)

The first thing that struck us about Easton, New York was its emptiness: long, open expanses of farmland, occasionally broken up by a cluster of cows. It was, after all, about 6:45 a.m. on a Sunday.

We had an appointment at Burton Hall, a century-old hillside meeting house with a large stage that had historically been used for pageants and recitals. Until recently, the stage had been co-opted by the Town Court because it had no room to operate, so the building was raised two feet off the ground to make way for new administrative offices beneath it. We met Aindrea Lundberg, a member of the town council, in the new addition.

Lundberg grew up in Easton, and her favorite thing about it is the cows.

“It’s just peaceful to go out there on an afternoon and just kind of wander among the animals,” Lundberg said.

According to Lundberg, 69 percent of Easton is agricultural land, primarily dairy and vegetable farming, but Easton’s small farmers have found the industry increasingly unsustainable.

Lundberg said that some Easton farmers are turning to solar energy generation to supplement their income, an initiative supported by Downstate politicians but a flashpoint for the otherwise civically disengaged town.

“We’ve kept out for the most part anything like Walmart,” Lundberg said. But with solar, “It’s very hard to keep that out.”

Lundberg’s personal skepticism towards solar stems from her and the town’s relationship with the land: she and her neighbors ride horseback and hunt on each others’ properties.

“We also don’t want to tell people what they can do with their own property,” Lundberg said. “So it’s really a tough situation.”

Some Easton farmers have gotten creative with making money in a tough economy.

Tiashoke Farm & Store, a local dairy farm, holds events aimed at attracting city folk, advertising uniquely rural opportunities like basket weaving or looking at baby goats.

Elisabeth asked if the town had a demonym, like “Eastonian.” It did not.

“It’s all farming,” Lundberg said. “They call themselves ‘farmers.’”

* * * * *

Easton, Maryland could best be described as curated, perhaps because half of its downtown is owned by one man: Paul Prager.

“He’s building his own little town,” said Bianca Russo, who we happened upon sipping wine with her friends Kerry and Trisha. “I call it ‘Pragerville.’”

Prager, a Brooklynite described by Eater as an “eccentric energy tycoon,” entered the Easton real estate scene in 2008 and quickly expanded to luxury dining establishments; he created a swanky salad bar after his daughter had a Chopt craving. His hospitality group now operates 10 of downtown Easton’s restaurants, a performing arts center and a bookshop billed as “independent.”

The locals are decidedly split on his impact, not just between themselves, but also within.

“Everything he does, he’s got the Midas touch,” Russo said. “Seriously, it’s beautiful.”

But in almost the same breath, Russo noted that Prager’s establishments cater mostly to the wealthy. One man we spoke to compared Prager to a model train enthusiast, an architect obsessed with crafting the perfect little world.

And perfect it was. Downtown Easton’s streets were lined with polished colonial and Victorian architecture. Beds of tulips rounded the sidewalk corners. Locals buzzed about in shamrock green, some evidence of the St. Patrick’s Day festivities to come.

We went on a private tour of Easton organized by the Talbot Historical Society. Our guide, Nancy Gooding, told of a town historically rife with racial tensions. Easton residents fought for both the Union and the Confederacy. Slave trading occurred in the market square, just down the road from one of America’s oldest free Black communities. Frederick Douglass was jailed in Easton the first time he escaped slavery – he returned decades later a free man with significant political influence, staying in a hotel overlooking the jail.

Today, a bronze statue of Douglass stands outside Talbot County Courthouse in downtown Easton. Prager partially sponsored the statue.

Easton goes to great lengths to maintain its historic aura. A 191-page document governs the design of every downtown building.

“If you want to change a window, you need to get permission,” Gooding said.

But Easton has made an appeal to the modern by becoming a hub for the arts.

“It has a lot going for it for a small town,” said Beth, the owner of an Easton puzzle shop who joined our tour with her dog, Bug. “A lot of theater. A lot of music. A lot of people who want to buy puzzles.”

Easton has also adopted a number of quirky traditions. The town has held a Crab Drop each New Year’s since 2005, one at 9 p.m. for the kids (known as “Midnight in the Mid-Atlantic”) and another at the actual midnight. The town’s St. Patrick’s Day parade used golf carts instead of floats until this year when it became a walking parade.

After grabbing some takeout, we met Mayor Megan Cook, who wore a “Taters Gonna Tate” shirt, at the parade starting line. We hadn’t much time to chat – she had to walk in the parade and, immediately after, compete in the annual Potato Race (think egg-and-spoon race but with raw potatoes). Her team lost.

With the parade beginning soon, we rushed to find an empty space on the curb where we could sit. We opened our takeout containers and began to eat as an army of children in green marched by.

Remy Oktay ’24 and Lucie Lagodich ’22 contributed reporting.

The trip chronicled in this article was sponsored by Bradbury Dyer III ’64 and the Dyer Center.

Jeff Kirby • Apr 10, 2024 at 11:19 am

Love your initiative and inspiration in making this journey and, now, your reporting on it. Got my pilot’s license during my freshman year at Lafayette in January 1981, and have enjoyed many visits to towns across the U.S. over the subsequent 43 years. Bravo to you all.