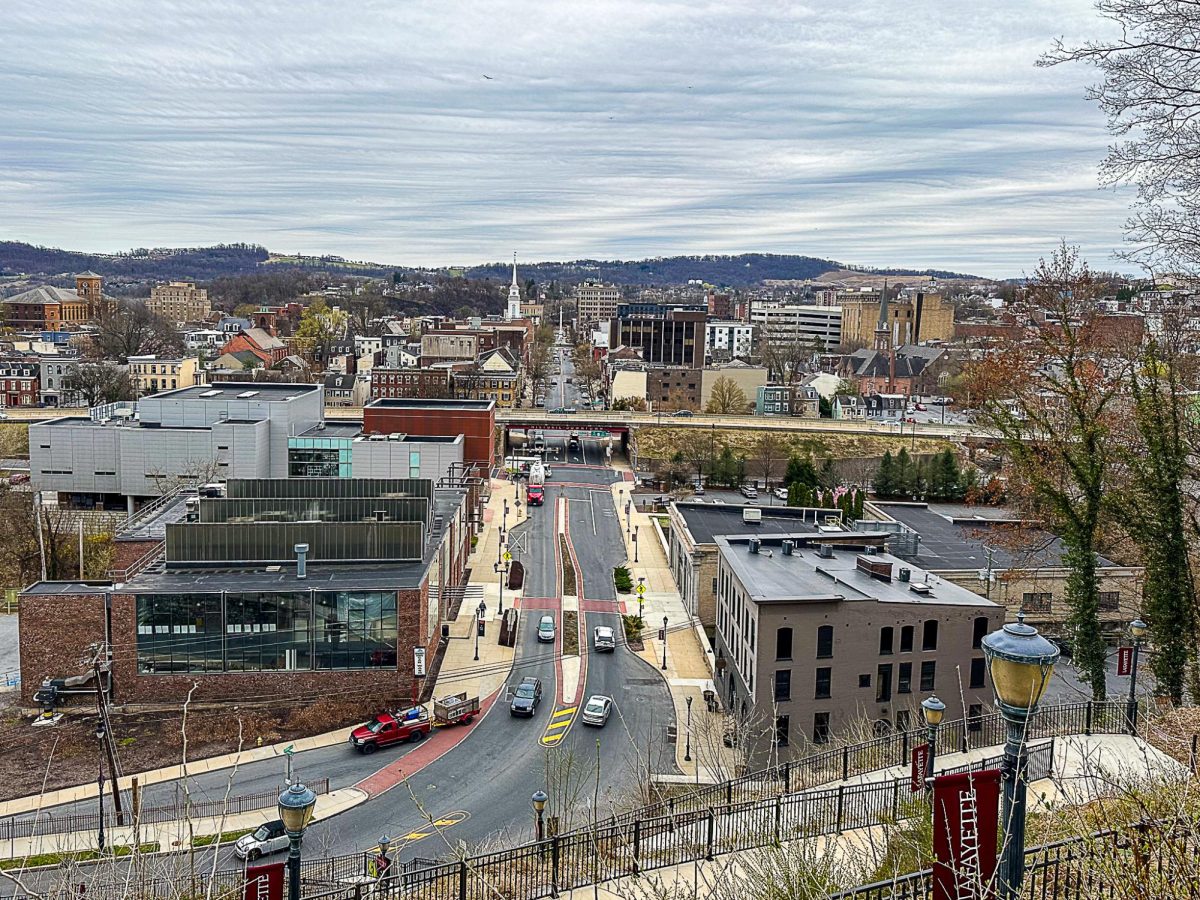

Questions of race and diversity continue to be debated on college campuses across the country. In celebration of Black History Month, The Lafayette dug through the college archives to examine the long history of black students on campus to highlight their struggles and triumphs throughout the years, starting from Lafayette’s very first class.

Lafayette College opened its doors in 1832. Within that first matriculating class was Aaron Hoff, the first black student that attended this school.

Two enslaved students from Louisiana entered Lafayette in 1836—David and Washington McDonogh. Although they were freed shortly after their arrival to campus, discrimination still persisted. According to Margaret Junkin Preston, daughter of the college president at the time: “They were kept and taught wholly apart from the students, who would have never consented to their presence among them.”

However, when Thomas McDonogh Durnford arrived on campus four years later, he was treated differently from David and Washington. Although he still experienced discrimination, he lived in the same building as other students.

In total, there were 10 students of color enrolled at Lafayette between 1832 and 1846. But, after 1847, there would not be a black student enrolled at Lafayette for 100 years.

Finally, in 1947, Lafayette admitted two Tuskegee Airmen, Roland Brown ‘49 and David Showell ‘51. Brown, who would later serve later on the board of trustees, and Showell were a part of the Sun Bowl controversy, which hit Lafayette the following year. The football team had received a bid to play in the Sun Bowl, but was told they could not bring their black teammate.

Students were appalled by the restriction, and in response denied the bid and protested their black classmate, according to a recent article in The Guardian. This was one of the first civil rights demonstrations to occur on Lafayette’s campus.

About a decade later, Lafayette students were still protesting racial discrimination. In 1956, Phi Kappa Tau pledged two black students. When the national fraternity refused to accept those black students as members, each member of the fraternity resigned from the national chapter.

“It is impossible for me to adhere to both the principles of brotherhood and racial segregation and still think myself of an intelligent human being,” wrote Phi Kappa Tau brother, James Voresmarti Jr. on Oct. 23, 1956.

Increasing numbers of black students were admitted beginning in the early 1960s. In this decade, the college awarded Ronald Brooks ‘65 the Pepper Prize, making him the first black student to win the award.

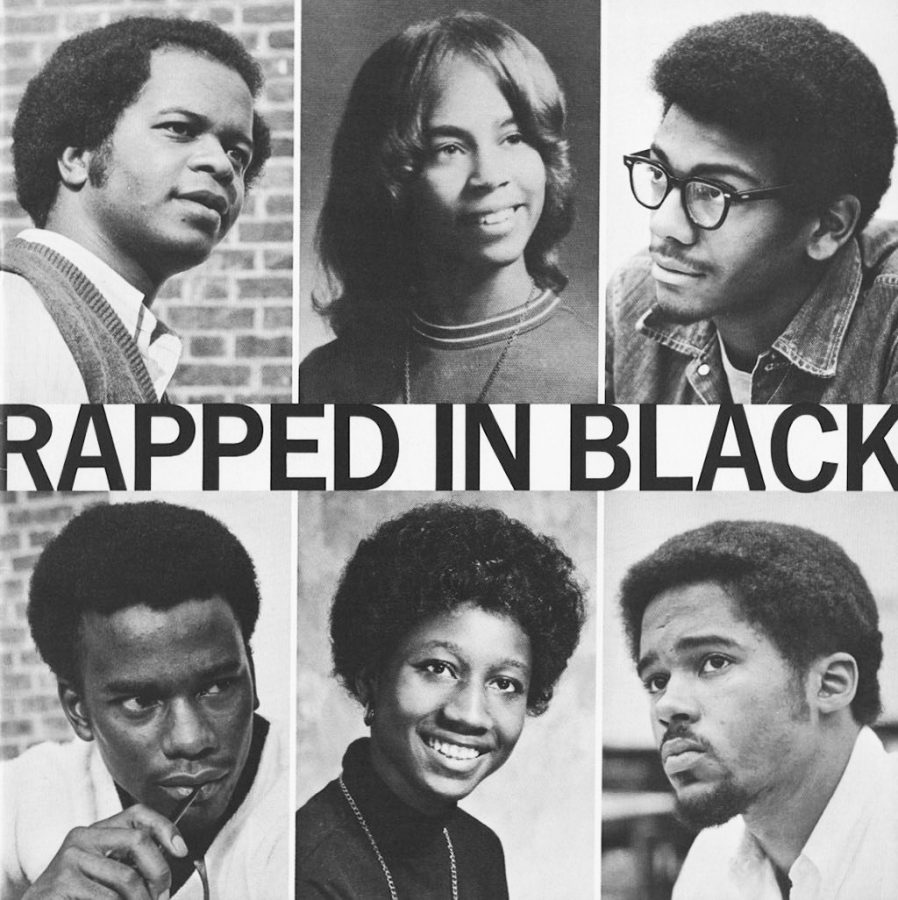

The Association of Black Collegians was formed, and in 1969, they published “The Black Manifesto”. This document stated demands from black students to the administration. The group asked for more black students, more black faculty, a “black studies program,” an end to racism on this campus and a house to serve as cultural center, according to an issue of The Lafayette in 1969.

In 1970, the first year Lafayette began admitting women, the college’s first black women students were admitted to the college. That same year Kenneth Rich ‘67 was the first black person elected to the Lafayette College Board of Trustees. Earl Peace ‘66 became the first black, full-time professor at Lafayette when he received an appointment in the chemistry department in 1971.

Between 1970 and 1975, an aggressive campaign to recruit black students for the college was led by Dean David Portlock, the namesake of the Portlock Black Cultural Center.

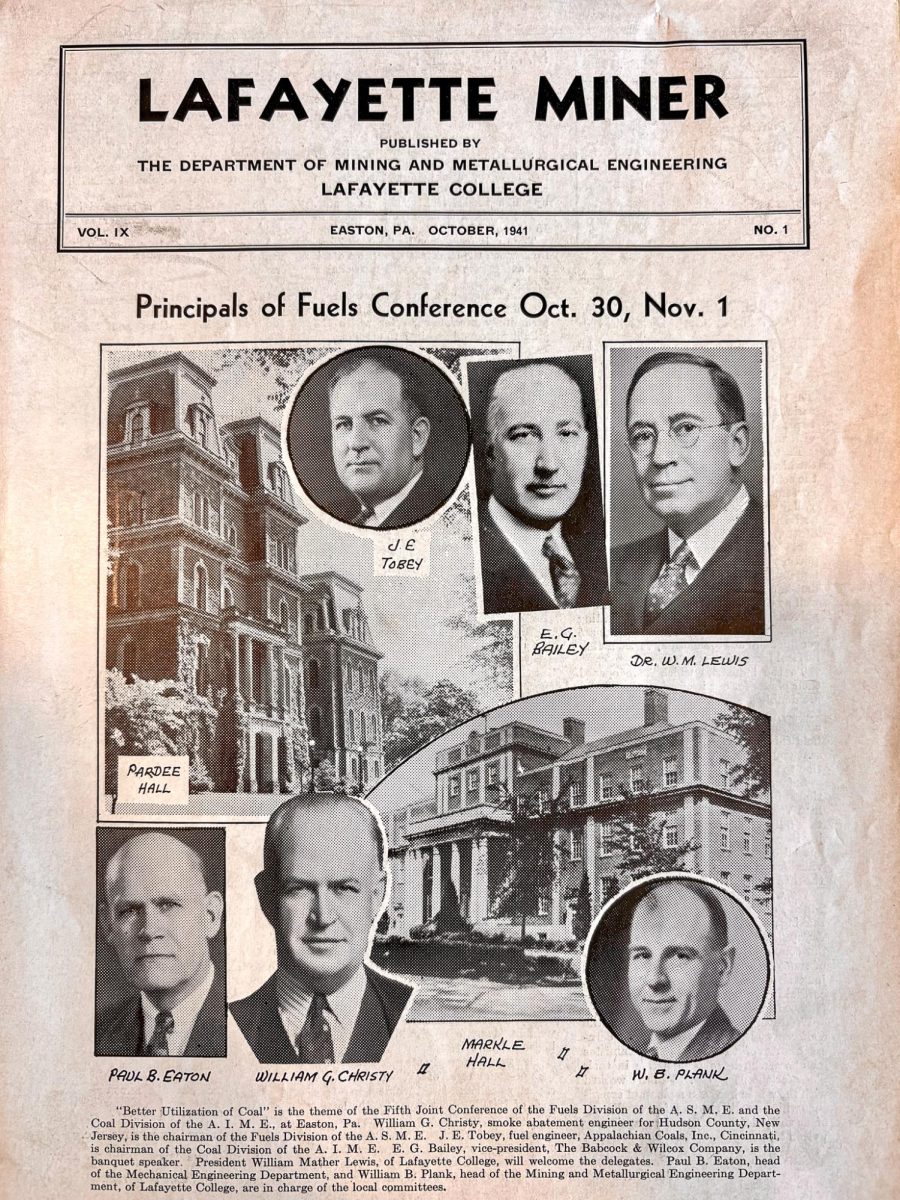

There are currently two areas on Lafayette’s campus that commemorate black students. In 2008, a sculpture was dedicated in memory of David McDonogh. It is located between Skillman Library and Markel Hall. It was named “Transcendence” to commemorate what David had overcome to become a successful physician in New York City. Additionally, there is an exhibit in Pardee Hall on the first floor to commemorate David, as well as nine other black students that attended Lafayette during its first two decades.