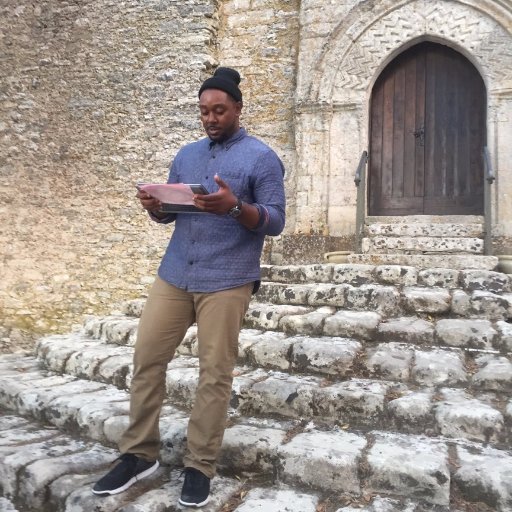

While many people find themselves amazed by the beauty of art and monuments, they may not take the time to truly understand the history or symbolism behind them. Author Irvin Weathersby’s forthcoming book, “In Open Contempt,” takes its readers on this journey of education and recognition.

Weathersby, the Brooklyn-based author and professor, read an excerpt from his forthcoming book “In Open Contempt” to listeners over Zoom this past Tuesday. The reading was the second event in the Closs Virtual Reading Series, following last week’s reading by Sarah Shun-lien Bynum of her novel “Many a Little Makes.” The series was organized by the English Department in collaboration with the Ruth Mary Callahan Closs Fund.

Weathersby was named the 2019 Bernard O’Keefe Scholar in Nonfiction at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference last year, and he currently teaches composition and creative writing at Queensborough Community College.

At this event, Weathersby read from his most recent project, a memoir in which he weaved in his travelogues with art history as methods of delivery. He began with his experience as a new professor of art history, describing the challenging task of effectively teaching his primarily adult audience a subject where he himself was a novice, before finally finding hope in the form of a transformative school trip to an art museum.

This segued into his own first experience of “feeling the power of museums” at the plantation home of Thomas Jefferson, at which point the conflict of racial segregation was introduced in the excerpt. He ended with another anecdote about an encounter with white supremacists.

The brief reading was followed by further discussion and questions from the audience.

“What was your experience growing up in New Orleans around monuments and streets connected to slave holders or symbolic of the slave trade?” one participant asked.

In response, Weathersby said, “When I was a school boy, there was a big movement to rename a number of our schools, led by my parents and other community leaders of my parents’ generation who took it upon themselves to say ‘why are we honoring these slave holders on school houses?’ That was one of my first conscious engagements with these phrases.”

Weathersby further talked about growing up in the age of David Duke, an explicit white supremacist and former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, and, at the time, an elected official in his neighborhood.

“It was very obvious to grow up in New Orleans and the deep South and recognize that there are certain places where you shouldn’t be, certain things that you shouldn’t say,” Weathersby said.

When asked about the root of the fear felt by many white supremacists, something that arose in his reading, Weathersby said that the biggest fear faced by supporters of white supremacy is losing the privilege that they previously held.

“[The monuments] are symbols of our thought process, our actions, our beliefs, and because they are so beholden to these things, they’re really trying to hold on to the days of yore…to the ideas of [past] grandeur,” Weathersby said.

Weathersby said he had been working on the book for a long time, but the murder of George Floyd earlier this year was “an incredible marker” for him to say “the world is ready for this and I just have to commit.”