Bonfires, like this one from 1904, became a traditional way to celebrate victory over Lehigh.

Photo Courtesy of Lafayette College Archives

Even those not on the team competed against their rivals

The rivalry between Lafayette and Lehigh culminates in a calculated score, but its history extends beyond the field. As the competition grew in age, students without numbers on their backs participated in and developed the rivalry just as much as the students fighting with them.

When the first Laf-Lehigh game was played in October of 1884, it was no surprise Lafayette emerged as the victor. The Lafayette team had been organized for two years, while only three Lehigh players had ever played before, according to College Archivist Diane Shaw, who gave a series of lectures on the rivalry in the past week in anticipation of the 150th game. The score was 56 to zero.

By 1891, the rivalry already developed into a heated contest. The third game of the year had to be played at a third-party location, in Wilkes-Barre, to avoid favoritism, according to Shaw.

Around the turn of the century, Lafayette students began building bonfires to celebrate the game against their rival. Around this time, each college’s administration agreed to only play annually, because the players were getting injured too much, according to Lehigh graduate Bob Donchez.

“For a rivalry as intense as this was, it was in the best interest of everybody just to play the last game of the season,” said Donchez, who co-wrote a book on the Laf-Lehigh rivalry with Todd Davidson and recently published a 150th anniversary edition. “They thought it was an appropriate climax to the year.”

In 1915, Lehigh suffered a significant upset at the hands of their rival. After winning 13 consecutive games in their home stadium, Lehigh faced the Maroon and felt confident enough about the game at halftime to display a casket with the inscription ‘Lafayette.’ Lehigh lost 35-6.

During World War One, however, the attention of each school was not on a sport but on an overseas conflict, and it was suggested that all intercollegiate athletics should be discontinued for the remainder of the war.

“Nearly every football player enlisted in the army and several poor season followed,” Associate College Archivist Elaine Stomber said in her presentation with Shaw. “In 1917 Lehigh defeated Lafayette by the largest score ever recorded in the rivalry, 78-0.”

After the war, the Laf-Lehigh rivalry entered into a 30-year period in which Lehigh won only four times. The 1920s were especially strong for the Lafayette team, who won two national championships, had a perfect record in a season, and even intimidated the University of Notre Dame team.

“Notre Dame and Lafayette entered into an agreement to create a series of games every year,” Donchez said. “And at the last minute, Notre Dame backed out of it…because of Lafayette’s strength.”

Following the collapse of the stands under the pressure of the fans, Fisher stadium was constructed in 1926 and could hold 18,000 spectators. In the same year, Lafayette won their third national championship.

After the war, Lafayette lost their power to dominate and the lower power difference led to an rise in student rivalries. Peace treaties were sometimes required to control the unruliness, according to Donchez.

The decoration of fraternity houses became a common way for Lafayette students to express their loyalty to their college. One elaborate decoration in 1947 depicted a Lehigh goose laying a eggs representing the zero scores in recent games. Before the 100th game, the leopard statue at Lafayette was painted Lehigh brown.

Some decorations nonetheless had alternative motivations. In 1966, the Phi Kappa Psi house constructed a large signing reading “Lehigh Shall Die” and only lit up the first letter of each word at night.

In the same year, Lafayette students distributed fake issues of Lehigh’s student newspaper The Brown and White to Lehigh students, urging them to all report to administration because they had lost their draft papers.

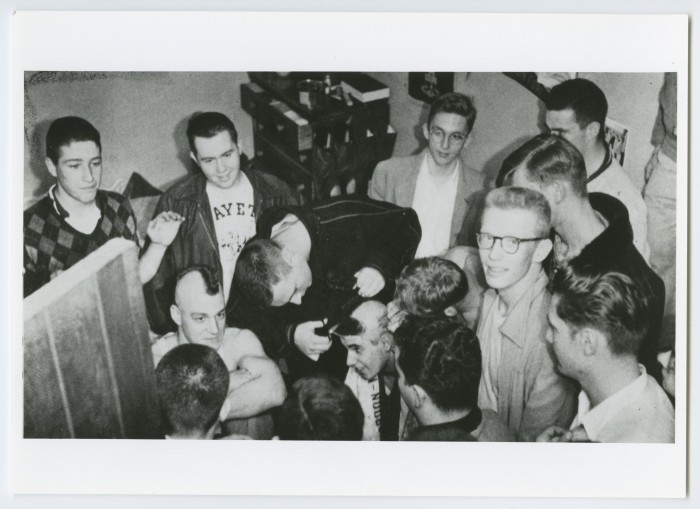

In the 1950s, when Lafayette students caught Lehigh students tampering with the traditional bonfire, they captured them and shaved “L”’s into their hair. According to Donchez, each college would do this to the other, differentiating with “LC” and “LU.”

When women were admitted to campus, they also created their own “powderpuff” football rivalry with Lehigh, winning their first game against Lehigh 30-0.

Lafayette students used their studies in engineering to provoke their opponents. These students developed a device “like an oversized slingshot” that flung eggs across the field, according to Donchez.

“Even though it was designed by engineers, the accuracy wasn’t necessarily the best,” Donchez said. “Except for one year when Lafayette students scored a direct hit on the assistant dean at Lehigh, right on the lapel of the dean’s brand new blazer.”

In addition to student protests about policies at Laf-Lehigh games in the 1990s, the Marquis de Lafayette statue needed to be boxed away when the annual game came around, as it was too often tampered with by Lehigh students.

“This plant operations tradition no longer seems to be necessary and we haven’t seen the Marquis boxed in a number of years,” Stomber said.

There is little record of pranks and other acts of student rivalries in more recent years. Although students’ expressions of rivalry are often not publicized before their occurrence, the anticipation to the 150th anniversary reveals that feelings of rivalry are anything but lost.