Why the Marquis’ legacy is seldom challenged

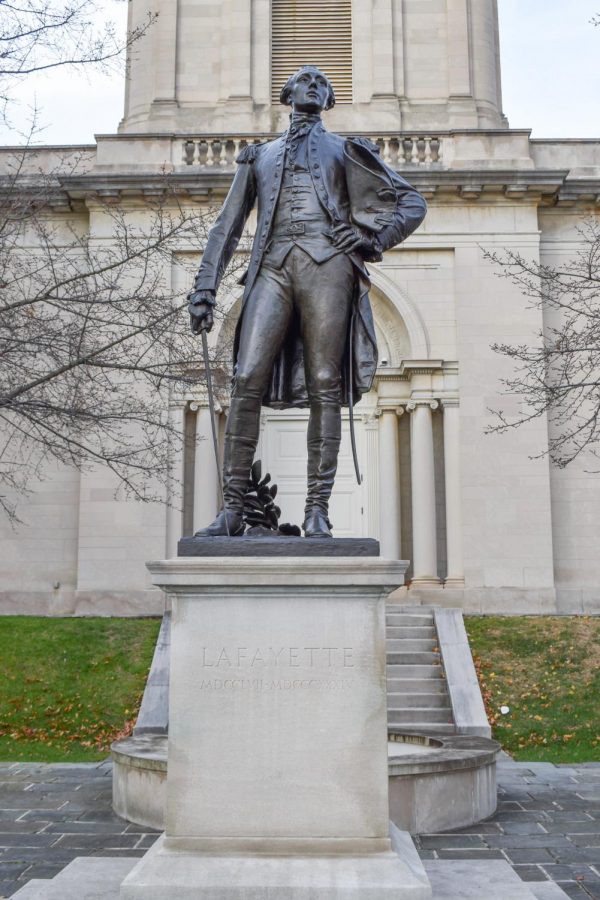

Unlike his acquaintance George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette was a staunch supporter of the emancipation of slavery. (Photo by Emma Sylvester ’25)

December 10, 2021

In the past decade, individuals renowned for their roles in founding the United States such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, have seen their legacies challenged and statues torn down as the public has brought their racist pasts into the public discourse. However, one individual who has seemingly avoided such negative attention is the Marquis de Lafayette, the namesake of Lafayette College and a French hero of the American Revolution.

Director of Special Collections and Archives Thomas Lannon noted the lack of controversy surrounding the legacy of the Marquis detailing how he wasn’t part of the slave-dependent “agrarian South,” something that separated him from founders like Washington and Jefferson.

“We still have them on our money,” Lannon said. “We have George Washington still on the dollar bill. It’s gonna take a long time to undo this, the symbolism of the American founders.”

In regards to the trend of statues being removed, Lannon stated that men like Washington and Jefferson still had an influence on society compared to Confederate secessionists from the American Civil War, who had seen much more criticism because of their more blatant ties to slavery and racism.

On the connection between Lafayette and his opposition to American slavery, Lannon mentioned a particular moment in 1783 where Lafayette wrote Washington about a “wild scheme” that he would commence “once the war for independence has ended and the Treaty of Paris was signed.” The scheme would have Lafayette purchase a plantation in what is now French Guiana with the intention of gradually freeing the enslaved workers and providing them with education. This was supposed to set an example about the possibility of the gradual emancipation of slaves, according to the Lafayette Society.

Former Director of Special Collections and Archives Diane Shaw, speaking on the 1783 experiment, said that while Lafayette did own slaves, this was done only for the sake of the experiment, explaining how the goal was to see them free once they had acquired new skills. While Lafayette admitted that his experiment was “wild,” he would not be deterred.

However, Lafayette’s plan of gradual freedom for slaves would ultimately not reach fruition. As Shaw explained, many individuals desired the immediate emancipation of slaves, not the slow process that the Marquis had in mind. Nevertheless, this did not end Lafayette’s ambition to protect human rights as much as possible.

“In Lafayette’s idea, he wouldn’t have fought in the revolution had he known it would have led to the continuation of slavery,” Lannon said.

Shaw added that Lafayette’s opposition to slavery began “very early in his life,” such as when he arrived in South Carolina at age 19 and “the first people he saw were slaves.”

Lafayette’s aversion to slavery persisted despite being friends with the likes of Washington and Jefferson, both of whom were slave owners.

“Neither of them freed their slaves in their lifetime despite Lafayette’s requests,” Shaw added.

Lafayette went on to champion emancipation, with instances such as meeting with slaves during the War of 1812 and having “shook hands with everyone,” according to Shaw. She detailed how the Marquis fought for human rights throughout his life, from aiding Native Americans and oppressed French Protestants to being a member of the French Revolution.

As posited by Lannon, the Marquis “represents the best aspects of American independence.”