Beginning next fall, the administration will be taking over aspects of sexual assault peer education at the college. This shift marks a change in the way peer education has been done on campus for years. In fact, students have been educating their classmates on sexual assault for decades, often without any administrative support at all.

Since the 1970s, peer education has taken place in various halls and houses across campus under many different names. Many of the challenges these peer educators faced have remained the same: struggling to be taken seriously, leading the only known safe space on campus for survivors of sexual assault and trying to enjoy their college years while burdened with being the only visible advocates of a problem much deeper than the administration would often admit.

So while peer education and attitudes around sexual assault continue to evolve, here is a look at some of the student groups and individuals that did whatever they could to educate their fellow Lafayette students and make the campus a safer place.

Women’s Caucus

Women’s first years at the college after being admitted in 1970 included a fight for safety on campus. In 1973, a group of female students formed the Women’s Caucus, the purpose of which, according to its constitution, was to “create a campus-wide awareness of women as human beings.”

The Women’s Caucus held events relating to women’s rights including sexual assault. They sponsored meetings with the Rape Crisis Council of the Lehigh Valley and created a Women Against Rape program to run in the month of November.

Peer education at this time was directed largely at female students so they could protect themselves from sexual assault. For instance, when resident advisors showed female students a film titled “Rape, Victim or Victor” in 1975, The Lafayette reported that they “felt it was important to educate the women about the problem.”

Association of Lafayette Women (ALW)

In 1979, the caucus took a new name: the Association of Lafayette Women (ALW). The longest-lasting women’s group on campus, ALW continued the work of the caucus to “celebrate and empower women,” with a wide array of programs, including some designed to “promote an end to rape and domestic abuse.”

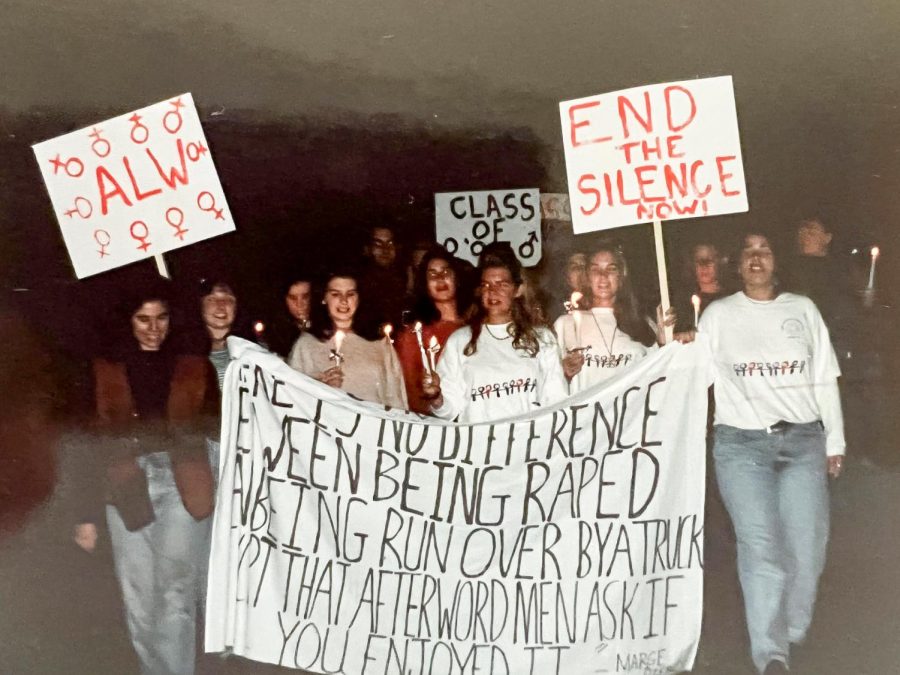

From their office on the first floor of Farinon Student Center, ALW brought many contributions to campus including women’s health information distribution, multiple performances of “The Vagina Monologues” and promotion of voter registration. They also organized the college’s first Take Back the Night event in October 1993.

At this event, almost 100 students marched through campus and nearby streets to show support for survivors of sexual assault. Before the march, the group held a candlelight vigil where some students shared their stories of how they or a friend had been assaulted.

While the administration was supportive of the event, according to its organizers, not all of the students took it seriously.

“There were a lot of people who laughed at it, they thought it was ridiculous,” ALW member Megan O’Neill ‘96 recalled.

Not all professors reacted positively either. Sociology Professor Howard Schneiderman submitted an article to The Lafayette titled “The myth of rape at Lafayette,” in which he criticized the event and declared that “there is no epidemic of rapes at Lafayette; in fact there have been no rapes at the school for at least the last six years,” referring to the lack of reported sexual assaults.

“Rape is not a problem at Lafayette, ideology may be,” the article ended.

Reactions like this did not discourage members of ALW from working toward their goal of making campus a safer place for women. ALW Co-President Kathie Butler ‘94 explained that because of their activist work on campus, students would approach group members and confide in them their personal stories of sexual assault.

“I can’t ever find my keys or phone but I can tell you exactly where I was sitting every time—thirty years ago—a student would confide an assault to me,” Butler said.

Without any formal training by the administration, however, ALW members could not do much more than comfort the survivors.

“It was just a bunch of well-meaning twenty-two-year-olds trying to make somebody feel better after something really devastating had happened,” she said.

ALW Co-President Jennifer Devlin Burke ‘94 recalled a lack of administrative support for their work. She wrote in a journal soon after college that “the constant daily battles for common respect practically drained me. Sometimes, I wondered why the hell I was carrying all this angst and why I couldn’t just go with the flow?”

Looking back, however, Devlin Burke said she only feels grateful that she met other like-minded students through ALW who also felt compelled to step up.

“I don’t even think we second-guessed it. It was just like, this is our duty and mission, and I never looked at it as a negative burden,” she said.

And ALW’s impact was felt by the campus at large, at least to some capacity.

“Certainly, there were a lot of conversations at the campus level that I think maybe would not have existed had the organization not been there,” ALW President Katrina Zafiriadis ‘95 said.

Butler added that despite the group’s successes, members were participating in a white, heteronormative kind of feminism. No students were out as LGBTQ+ at the time that Butler knew of, and most women participating in ALW were white.

“I think it was a product of its time, but I think we did the best we could with the language and tools that we had,” Butler said.

ALW continued to run events through the 2000s and early 2010s, eventually changing its name to the Association of Lafayette Feminists (ALF). By continuing to hold Take Back the Night vigils and inviting speakers to campus to address sexual violence, the group fought to make the campus safer for almost 30 years.

Campus League Against Sex-role Stereotypes (C.L.A.S.S.)

Formed in the fall of 1988, the Campus League Against Sex-role Stereotypes stemmed from ALW. At the direction of Karen Forbes, director of the counseling center, students in the group worked to “eliminate misconceptions and promote interactions between men and women, and create an awareness of sexual harassment and assault on campus.”

The group created skits around topics of sexual assault, namely date rape, and presented them at orientation programs and for Greek organizations—although every group they presented to had to include both men and women.

“We always insisted, if we were going to do this with a fraternity, a sorority had to be there too,” recalled C.L.A.S.S. member Laura Brader-Araje ‘91.

Brader-Araje said that students would come up to her after the skits and confide in her their own experiences with date rape.

“There was a celebration of rape culture. It wasn’t just that it was there, it was front and center, and the battle had begun,” Brader-Araje said.

She recalled how upperclassmen students often signed up for meal plans at fraternity houses, and upon entering the house, fraternity brothers would call out numbers to the women and shout vulgar things such as “Do you want to get raped today?” to their faces.

“What are you going to do? You’ve got to eat. So you sit with your girlfriends and you eat and you don’t process what you’re hearing to get through the day,” Brader-Araje said.

In another instance, Brader-Araje recounted walking near Colton Chapel alone one night when six or seven fraternity pledges circled around her and shouted, “you look like you want to be raped.” A senior at the time, Brader-Araje remembered not feeling threatened by the pledges, but she did decide to report it. Upon reporting the event, however, Brader-Araje received multiple threatening messages on her dorm room whiteboard and voicemail machine.

“It was my last straw. I just thought, if it wasn’t my senior year, I don’t think I would’ve gone back, not because I felt threatened but because this was just not a welcoming place and everybody deserves better, including me,” Brader-Araje said.

While C.L.A.S.S. facilitated discussions on campus through the early 1990s, its members did not have the answers for every question they were presented with.

“We were kids too,” Brader-Araje said.

Coalition on Rape and Relation Education (C.O.R.R.E.)

The Coalition on Rape and Relation Education was formed in January 1996. Made up of students, faculty and administrators (namely residence life), the coalition held frequent workshops in dormitories. Unlike C.L.A.S.S., these workshops took place through three programs: “Who Do You Know,” held for and led by female students, “Man to Man,” for male students and “Making Love at Lafayette,” a co-educational discussion on love, sex and relationships.

O’Neill, the creator of C.O.R.R.E., explained that discussions were optional and intentionally casual. Students would drop by in pajamas or while making popcorn in the dorms.

And the inclusion of male students in C.O.R.R.E. was intentional, according to O’Neill. A former president of ALW, O’Neill had spent much time advocating for women’s rights by her senior year and wanted to try a different approach to reach more students.

“People are hesitant to admit what they don’t know because they’re afraid they’re going to be attacked. So sometimes, the knowledge gap remains. And you can’t educate because no one can tell you what they know…our thought was just, ‘bring people in and facilitate a conversation,’” O’Neill said.

C.O.R.R.E. was one of Lafayette’s “fastest growing organizations” at the time, according to The Lafayette. When O’Neill visited the college at a reunion five years later, she stayed in South College and saw a poster from C.O.R.R.E. on the wall. The calendar featured well-known men on campus posing with quotes related to consent such as “No means no.” This C.O.R.R.E. initiative known as “Real Men” allowed men to take a leading role in campus activism on sexual assault. This calendar, to O’Neill, was evidence that the organization was something that people wanted to be a part of, even into the 2000s.

Pards Against Sexual Assault (PASA)

As ALF faded out of existence at the college in the 2010s, another organization was formed in 2017, one that current students all recognize today: PASA.

The group’s founding members described the campus they knew as a place where sexual assault was not discussed in any capacity.

“I think that our campus was ready to explode, and it needed a monitor or someone to give the space to have the conversations that people were wanting to have,” Nina Cotto ‘19 said.

PASA founders went through training themselves before bringing their curriculum to groups on campus such as Greek organizations. They also facilitated the return of the program Take Back the Night and instituted Sexual Assault Awareness Month. And like the groups before them, because their organization was seen as a safe space for survivors, many students came forward to tell members their stories.

“People would stop us individually wherever, at parties, at bars, on the way to classes, and pull us aside and tell us their story for the very first time,” Cotto said. “I mean, by the time I graduated, I probably heard about fifty people tell me their story for the first time.”

“[PASA] kind of enveloped our entire lives and identities at Lafayette. We were the only visible advocates on campus, but you don’t want this to be on your mind 24/7 because it’s very heavy stuff to think about…It was really difficult to separate yourself from the work because it was almost like people didn’t let you,” Samantha Arnold ‘18 said.

The knowledge of these stories weighed heavily on PASA leaders, especially since they knew that many of the survivors would never receive justice. Furthermore, knowing who the perpetrators of sexual violence were added even more burden.

“We would go do these trainings for fraternities, and I would be looking out into this room of like eighty guys…and I wouldn’t be able to say anything, but I knew exactly who the rapists were,” Arnold said.

Arnold also recalled some resistance to the “realities of sexual violence” that the group encountered in their first year. Despite any challenges they faced, however, PASA founders agreed that the work was necessary.

“I definitely felt the cost as time went on because we were doing everything that the campus should have been doing…I really dedicated everything to PASA, because again, if we don’t, who will?” Cotto said.

Arnold described a shift on campus in PASA’s first year, leading students to have discussions they weren’t able to have before. Nahin Ferdousi ‘19 described the impact as “shattering [a] barrier.”

“We were really respected on campus, and I think that’s because we treated everyone like a human,” Cotto said.

Now in its fifth year on campus, PASA is currently wrapping up programming for Sexual Assault Awareness Month. They held an in-person Take Back the Night vigil last fall after over a year of virtual events. The group has also extended its training to organizations beyond social groups and brought more peer educators onto their team than ever before.

PASA Co-President Libby Mayer ‘22 also emphasized her hopes that PASA’s future leaders will represent all identities since gender-based violence can affect anyone. In the meantime, PASA will continue to educate the campus, despite future increased administrative involvement.

“Peer education is essential, and it’s not going away,” Co-President Annika Murray ‘23 said. “It might change, but it’s always going to remain a really critical part of how college students learn.”

No matter what its future looks like, PASA will always be one of a long line of organizations making campus safer for women.

“It makes me proud to know that there’s a history of women on this campus taking a stance and pushing for change,” Mayer said.