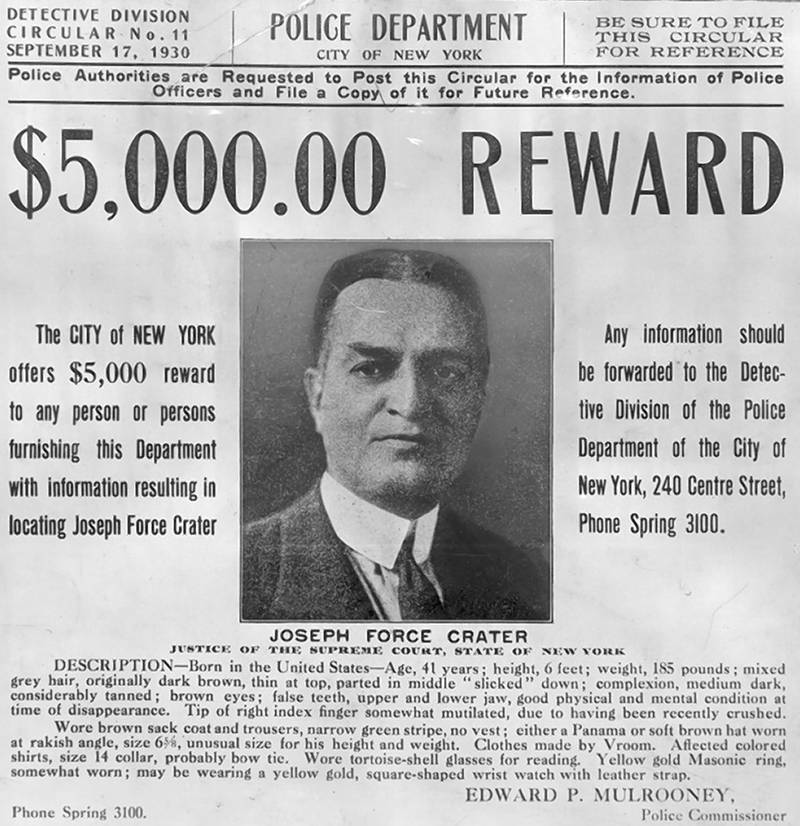

Corruption, political intrigue, showgirls, mobsters and New York City brothels were just a few puzzle pieces of the perplexing 1930 disappearance of Judge Joseph Crater, New York State Supreme Court Justice and graduate of Lafayette’s class of 1910.

On Aug. 6, 1930, Crater disappeared into the summer night and was never seen again. When his vanishment became public nearly a month later, it immediately became a national news sensation. The case still garners attention to this day, with true crime podcasts and even web series like Buzzfeed Unsolved taking a crack at finding an explanation that sticks. So, what could have happened to the judge that fateful night? There are several theories.

The least gory of these theories posits that Judge Crater voluntarily disappeared in New York, whether it be to go into the sunset with one of his beloved showgirl mistresses or to avoid being called on to testify in a political corruption trial.

Extensive evidence suggests that Crater purchased his judgeship, a practice common at the time, particularly among Tammany Hall politicians in New York in the 1930s.

“There’s no real question that Judge Crater bought his judgeship,” Richard Tofel, author of “Vanishing Point: The Disappearance of Judge Crater and the New York He Left Behind,” said. “We know that he withdrew and doesn’t seem to have redeposited an enormous amount of money — $22,500 — right around the time he got his judgeship, which was the annual salary of the judgeship, which was the usual amount that people paid when they paid,” Tofel said.

“There were a lot of theories that he had disappeared to avoid scandal — political, legal or sexual,” Stephen Riegel, author of “Finding Judge Crater: A Life and Phenomenal Disappearance in Jazz Age New York,” added. “There was a political scandal involving judicial office buying, which implicated a very close ally and friend of his.”

However, Riegel and Tofel agree with the theory that Crater disappeared not because he fled the country, but because he died.

“I am quite convinced that he died that night and somehow ‘got disappeared,’ and really disappeared so that when people were looking for him a month later they could not find him,” Tofel said.

Tofel theorizes that Crater’s death had something to do with his propensity for spending time with prostitutes. He bases this belief on the memoir of Polly Adler, a brothel owner in New York City.

“There’s some reason to think that, in an early draft of her memoir, [Adler] suggested that she knew what had happened to him and that he might have been a customer of hers that night and died, as they say, ‘in flagrante delicto,’” Tofel said, suggesting Crater died during a sexual act.

“That actually sort of fits the bill, and the reason it fits the bill is it would have been entirely characteristic of him,” Tofel continued. “[Adler’s] business partner, who was Dutch Schultz, was a very well-known mobster who was personally an enormously violent guy, and the kind of person who could have made somebody disappear, literally without a trace.”

Riegel, on the other hand, traces Crater’s assumed death back to his Tammany Hall involvement.

“I think all the evidence really strongly supports a theory that he was involved in a Tammany Hall political scandal. That’s based on a lot of reasons, but I think it’s especially strong if you do a timeline,” he said.

According to Riegel, newspapers from the days leading up to Crater’s disappearance shed light on the fact that the walls might have been closing in on his and his associates’ involvement in political corruption.

“[Crater] had just come back from his summer cabin in Maine about three days before he was last seen, and if you look at the newspaper headlines — what was happening those days, what was affecting him and who the people in the news were that he was close to — I think it begins to really all fall into place,” he said.

Riegel believes Crater was planning to leave town to avoid being called to testify against his corrupt friends, but they instead made sure he was silenced permanently.

“He was interrupted in his efforts to flee and was basically knocked off because he knew too much,” Riegel said.

Riegel and Tofel also agree that the legal implications of Crater’s return made the police less than motivated to find him.

“Tammany Hall very firmly controlled the city government at that time. The mayor was Jimmy Walker, who was a Tammany loyalist, and the whole city — the prosecution, the city attorneys, the department heads — they were all Tammany people. And so there’s a lot of evidence that they didn’t want to find him, especially the prosecutors who were involved in these other scandals that were breaking probably knew that [Crater] was very knowledgeable,” Riegel said.

Although Tofel doesn’t believe Crater’s death was a direct result of his Tammany Hall connections, he agrees they played a role in hindering the investigation into his disappearance.

“The New York City Police Department in 1930 was rotten from top to bottom,” he said. “There were a lot of people that, once Crater had disappeared … didn’t want him found, and they wanted as little made of this as possible.”

Judge Crater was declared legally dead in 1939, nearly nine years after his disappearance. With no concrete evidence and most of the involved parties now dead, it is unlikely the truth of his disappearance will ever surface.

Even those who have researched the case extensively are open to many possibilities.

“Is it possible that this guy went off to the Brazilian rainforest and was never seen again? Sure. It’s possible,” he said. “But I don’t think it’s too likely.”