Because of its towering stature, role as a home for a variety of educational departments and location in the center of campus, Pardee Hall serves as a symbol of Lafayette. But the history of Pardee Hall is not quite as immutable and steady as its construction may suggest — in fact, since its original construction in 1873, the building has faced numerous extensive renovations after two destructive fires.

The first fire occurred in 1879 when an accident in a top-floor chemistry lab destroyed much of the building. Just 17 years later, the building was once again ablaze.

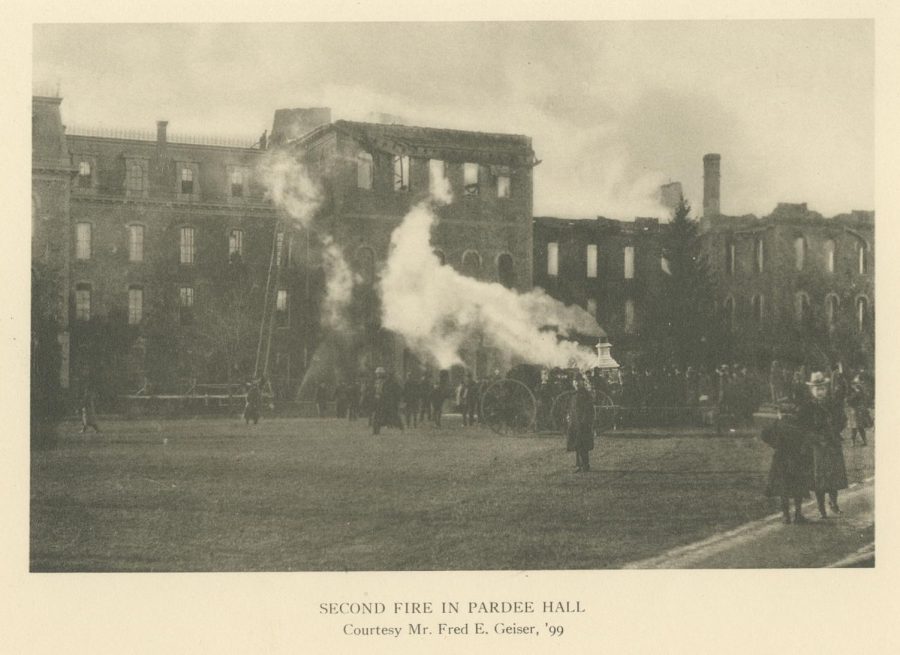

The second fire, which tore through Pardee Hall in 1897, is extensively documented. Often considered one of the most dramatic events to occur on campus, the fire received thorough news coverage as well as a several-chapter-long feature in library namesake David B. Skillman’s “The Biography of a College,” a densely packed series of books on the comprehensive history of Lafayette.

College janitor Jonas Walters noticed the blaze on an early December morning. Walters promptly ran to report it to the local fire station. It is believed that the College Hill firefighters who first responded to the alarm were poorly trained, and with many of them reportedly under the influence, the damage caused by the fire was far more extreme than it would be today.

Although the building’s exterior walls were almost entirely unaffected, the majority of the interior had been burned to the ground. The college experienced tens of thousands of dollars in property damages and lost several invaluable collections of literary materials and geological minerals.

Investigators searching for the cause of the blaze pointed to a recently shellacked whiteboard, reasoning that the item could have easily caught flame, as well as to faulty wiring, a vague explanation often employed in reports of unexplainable fires of the time. It wasn’t until the summer of 1898 that Lafayette College made national headlines when, almost six months after the initial incident, the true cause was discovered — and neither flammable varnish nor an electrician’s poor workmanship was to blame. Instead, the culprit behind Pardee Hall’s second crippling fire was a disgruntled former professor.

Lafayette hired George H. Stephens as an associate professor of moral philosophy in 1894, and after several turbulent years of employment, he was released from the position in 1897. Enraged by his dismissal, the professor set out to execute a series of criminal acts. Local newspapers, such as The Philadelphia Press, attributed these acts to his determination to ruin the reputation of the school, and especially that of its president, Dr. Ethelbert Dudley Warfield, whom Stephens pointedly blamed for his termination.

The torching of Pardee was Stephens’ first act against the college. In a transcript of his confession to the police, portions of which are available in “The Biography of a College,” the former professor speaks in detail about his process, how he searched Pardee “from one end to the other” for anything that could burn, piled a biology lab full of wooden furniture with a lab gas jet at the base and touched the pyre off with a blue-headed match. His reasoning, he confessed, was, “It was right and duty then, I thought. I was gone and why should there be anything left?”

Having destroyed Pardee, Stephens moved on to perpetrate acts of vandalism in the months before his arrest. He mutilated the reeds and valves of the chapel organ, rendering it unusable, and cut the vines adorning the exterior walls of South College, killing the plants that had been growing to completely shroud the building for almost a decade. Additionally, Stephens tossed the chapel’s Bibles and hymn books into a cistern behind South College and spread an abundant amount of tar around the whole interior of the chapel.

Had Stephens not been caught, these schemes would have continued. On the night his identity was discovered, the professor confessed that he had been attempting to spoil Colton Chapel by throwing at it a basketful of rotten eggs. Stephens also confessed to plotting to set fire to the chapel the following winter.

According to an article from The Philadelphia Press found in the College Archives, in February of 1899, after a week-long trial with over 100 witnesses, Stephens was proven guilty and sentenced to nine years in Philadelphia’s Eastern Penitentiary. His case would go on to be studied and published in prominent publications like the American Journal of Insanity, now called the American Journal of Psychiatry, under titles such as “George H. Stephens – Insane or Criminal?”