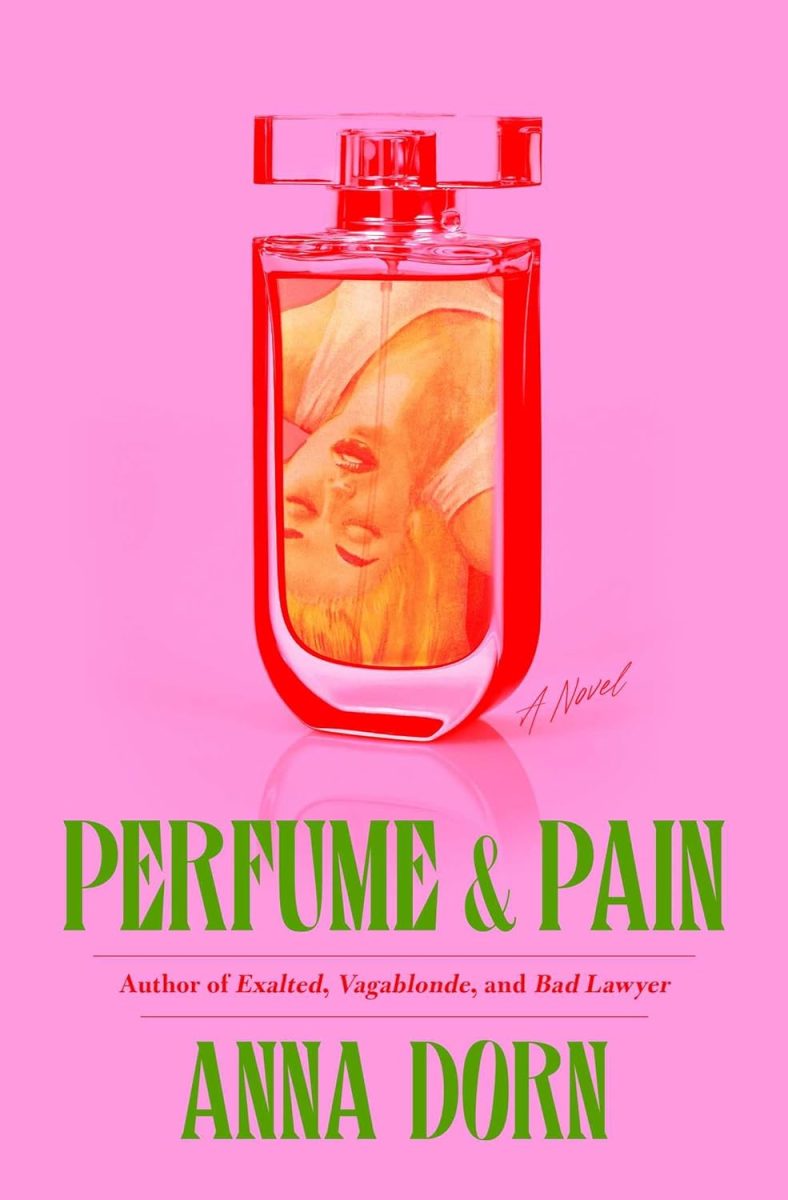

I’ve never seen “Pulp Fiction” (1994). I know. I’ll get around to it eventually. But I have read pulp fiction or at least a novel heavily inspired by it: Anna Dorn’s most recent release, “Perfume & Pain,” named after a real lesbian pulp fiction novel from 1962.

I don’t want to bury the lede; this book is about a snarky, self-destructive, hedonistic writer in Los Angeles with an addictive personality who simultaneously hates and makes intelligent comments about everything and everyone around her. A part of me looks down on Astrid Dahl, the other finds her endearing.

“a book that dares to ask, ‘what if bojack horseman was a human lesbian?'” reads the top comment on the book’s Goodreads page.

Let’s get some definitions out of the way before I continue. Pulp fiction is a term derived from pulp magazines: cheap, mass-produced fiction popular from the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. Beyond the era of “the pulps,” it connotes entertaining, inexpensive literature — most notoriously associated with themes of sex and violence.

Lesbian pulp fiction is pulp fiction about lesbians (shocker!). With provocative covers, sensationalized plots, male authors and punishing tragic endings, the genre was not a progressive movement (though there are exceptions). Despite these shortcomings, modern scholars recognize its importance in lesbian history and culture.

“Perfume & Pain” follows our protagonist and epicure extraordinaire as she claws to recover her career post-cancellation and hovers on the brink of violating her sobriety (her favorite trip — Adderall, alcohol and cigarettes — is named the “Patricia Highsmith” after a lesbian pulp fiction author). She copes with a perfume obsession and romantic interests sent her way, including an academic researching lesbian pulp fiction. Astrid’s glimpse of hope is an A-list actress’ interest in adapting one of her novels — if she doesn’t ruin it all for herself first.

If you’re waiting for me to explain more about the plot, I’m not sure what more there is to say. It’s a character-driven novel in which you hover over Astrid’s shoulder as she careens around Los Angeles, navigating an unwitting love triangle and learning important life lessons perhaps later than she should. The book’s Goodreads and back cover blurbs could do a better job summarizing it, honestly — so many details, so little to discover for yourself as a reader.

One of the main boasts of “Perfume & Pain” is that it’s funny. It’s biting. It’s also niche, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Astrid is engrossed in the modern queer culture of Southern California. Much of the novel’s commentary is specific to that realm and may not resonate with readers who don’t understand its references. But what is a book if not a portal into other worlds? At the very least, “Perfume & Pain” speaks well to its target audience.

The novel’s frequent references to pop culture were jarring for me — mentions of Twitter, Lana Del Ray, cancel culture, etc. — but maybe that’s just because modern romance isn’t my usual genre. It works for the novel and for a protagonist with a cynical and sarcastic opinion on everything current and popular.

Astrid’s narration is tolerable because she’s self-aware, to some extent. Dorn balances the cast of “Perfume & Pain” between those who try to ground her protagonist’s reality and those who just want to beam her up into an indulgent, druggy space with them. Astrid’s love interests, Ivy and Penelope, are by far the most interesting supporting characters, but her brother and friends are refreshingly orderly additions.

TL;DR — read “Perfume & Pain” if you’re intrigued by pulp fiction, if you watched “BoJack Horseman” (2014-2020) and/or are on queer subcultures of Twitter (or X, or whatever).