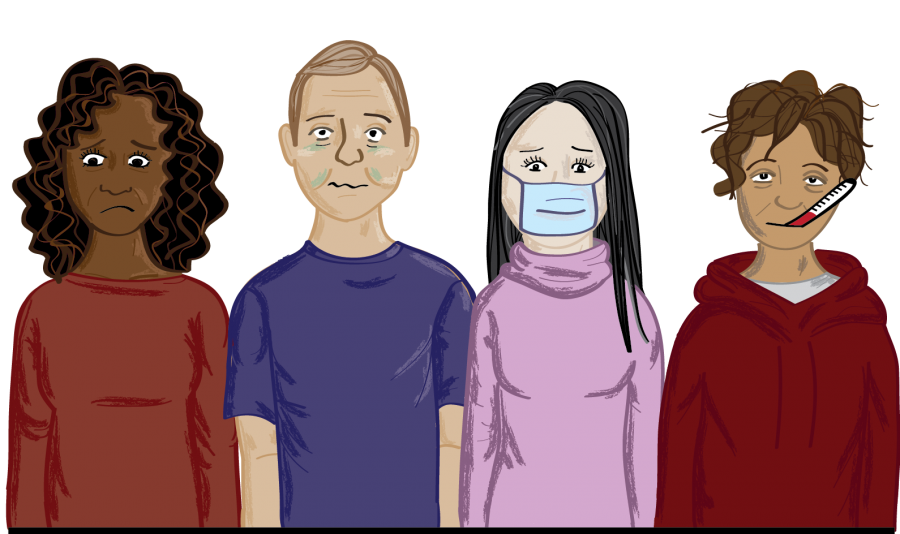

Early last week, a student felt like her skin was on fire. Another said she felt like she got hit by a truck. More missed classes. Public safety said they drove a few students to the hospital.

Bailey Health Center made a hard diagnosis. The flu made its seasonal debut on campus within the first week of the semester.

Eighty-four cases turned up at Bailey’s, and almost as many got dean’s excuses as of Tuesday. Not every $20 flu shot could keep up with the rate that the influenza virus mutated.

With no regard for such complex mutations and transmissions – and rumors of norovirus – I set out to track down the virus. Was there an origin?

I was naturally inspired by perhaps one of the most famous epidemiologists, John Snow, the subject of the class of 2019’s orientation book. Snow tracked the source of a cholera outbreak in London in 1854 back to a water source. When he turned off the water pumps, cholera cases declined rapidly. His discovery and methodology sent shock waves through many disciplines.

Last week, I asked close to 25 people who likely had the flu where they may have gotten the virus. I knew I couldn’t identify a source, and there was no way to “shut off” the pumps of the flu like Snow did, but I hoped that the investigation would highlight the diversity of connections across campus. It was hard.

The flu gives epidemiologists a headache because it is so contagious and can spread so ubiquitously. Yet it still occupies one of the main focuses of the Center for Disease Control and state departments of health because of its impact. Five to 20 percent of the country’s population contract it in a year.

The flu most often spreads in the simplest of ways, sometimes five feet can be close enough to contract the virus, and some experts believe even talking can spread it. On such a small campus as Lafayette, what could we learn from trying to trace down the flu to its “patient zero”?

As one would expect, I couldn’t find an explicit lineage of one strain of the virus. Most people could only pinpoint one person before them who probably gave it to them. One friend could remember one before, but when I’d ask that person, the trail would quickly go cold.

I began to realize the futility that Director of Health Services Dr. Jeffrey Goldstein warned me about. The state Department of Health says the flu is currently at its highest activity level: “widespread.”

“When you have an infectious disease that’s so widespread, there is no patient zero,” he told me – after I had already talked to about 20 sick students and staff.

“It’s ‘widespread’ times ten,” Goldstein said, who also had to take off work as a result of the flu, “because students live on top of one another, and share toilets and sinks and closed spaces, and contagious diseases tend to spread a lot more than do in [Easton].”

On one particularly lucky occasion, I think I found four students on the same lineage, tracing all the way back to possibly one of the first cases on campus, whose symptoms appeared on the first Thursday of the semester.

But I had to get outside my own friend bubble, so I crowdsourced over Facebook (which only found me more sarcasm than case studies) and asked people whose conversations I had (accidentally) eavesdropped. Friends started to be my surrogates, finding virus victims in their classes and dorms.

Each case only proved that you never know your transmitter. There were, however, some patterns in the places people would normally hang out and whether they found themselves at the mercy of the virus. Places like Upper and Skillman Library were common places that they had gone, but then again, so many others had gone there without getting the virus.

Biology professor Robert Kurt used to do a similar simulation in one of his beginner biology labs. Given the size of Lafayette and the rate of spread, the students would determine how many people could be affected by strep throat. The most important variable in their basic model was the speed of the test to determine whether individuals had strep throat.

“Because it’s a rapid test for the [bacterial infection],” Kurt said, “you can shut down epidemics faster if you get enough people realizing that they are infected and stay by yourself for a while and you can see the numbers drop.”

Understandably, if that student did not discover their illness until late in its development, they would have already been an agent of its spread.

In reality, not everyone will separate himself or herself from campus when they realize they are sick. Goldstein said he believes those 84 cases are only the “tip of the iceberg” of the real scene on campus, because so many people “self-treat.”

But in the end, the trouble with tracking influenza – as well as keeping yourself from it – is that it is so contagious and so widespread in so many different forms. Kurt’s model had a single introduction of a virus, but the flu is continually being introduced to campus as it comes in contact with people in the area.

I hope everyone with the flu feels better. Until then, I’ll be wondering why a week of talking to sick people hasn’t gotten me feeling under the weather.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story had strep throat described as a virus. It is a bacterial infection.

A Proud Alumnus • Feb 11, 2017 at 7:44 am

Wishing everyone a speedy recovery! Stay well, Lafayette!

A Proud Alumnus • Feb 10, 2017 at 2:54 pm

So, no luck finding patient zero, eh? ACHOOOOO! Excuse me. Cough….cough.