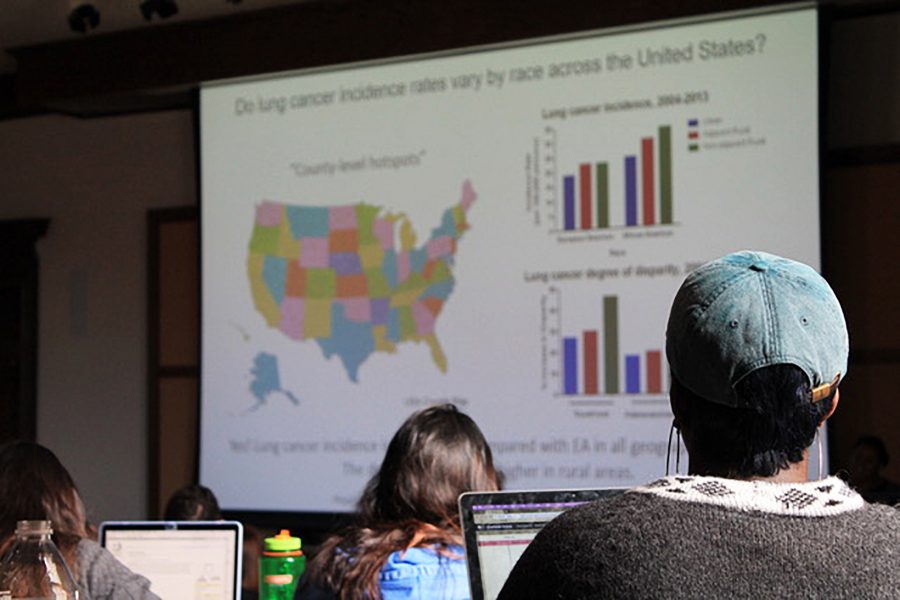

Khadijah Mitchell began her talk at the College by dispelling the myths that African-Americans smoke more than any other demographic and that they process nicotine differently. Why, then, do they have significantly more mortalities from lung cancer than white Americans? This is what she has been trying to answer through her research.

Mitchell, who has a Ph.D. in human genetics and molecular biology, said, “the real answer…probably lies in the second leading cause of lung cancer: radon.” African-Americans are more likely to live in older buildings or in areas with higher concentrations of radon, she said, and Lehigh Valley is one of these areas. Advising alarmed students, she said to “get a detector…they are often available for reduced prices through the EPA.”

“These disparities often come not from genetic differences, but from environmental ones,” she added. “Even when you look at the pan-cancer spectrum—and if you have cancer, it is going to show up here—some African-Americans don’t have any differences, which means the ancestral case is not always true.”

While much is yet unknown about what causes health disparities, Dr. Mitchell’s research has shown that different approaches are often necessary for treating different racial groups.

Mitchell’s talk was held this past Tuesday as a part of the new Interdisciplinary Seminar and Life Sciences series of lectures conducted by biology professor Michael Butler.

Mitchell has also been working on the question of why African-Americans respond to drugs differently than European Americans. By using prediction tools such as Cibersort, she is able to estimate if certain populations will respond to certain drugs.

She found that African-American populations do not respond to 53 drugs to which European Americans do respond, probably due to differences in their methylation profiles. To find methods that do work, Mitchell has been drawing from the fields of epigenetics and immunotherapy to find treatments that are more effective for African-American populations.

According to Mitchell, despite African-Americans being the group most affected by lung cancer, they are severely underrepresented in clinical studies. Adding that lung cancer studies in the past have been only 5% African-American compared to the United States 13% African-American population.

Alongside her ultimate goals of identifying and effectively treating cancer patients, Mitchell also strives for health equity, which she described as achieving “the highest level of health for all people across all populations.”

Mitchell said that this is achieved by reducing the health disparities prevalent in the United States, from underrepresentation in studies to unequal access to health information and facilities for certain groups. Increasing both individual and community knowledge on health issues is a key aspect of promoting health equity. Her team has been actively spreading information about lung cancer to the Lehigh Valley area.

Mitchell’s work is a step towards decreasing incidence and mortality for everyone, not just certain groups.