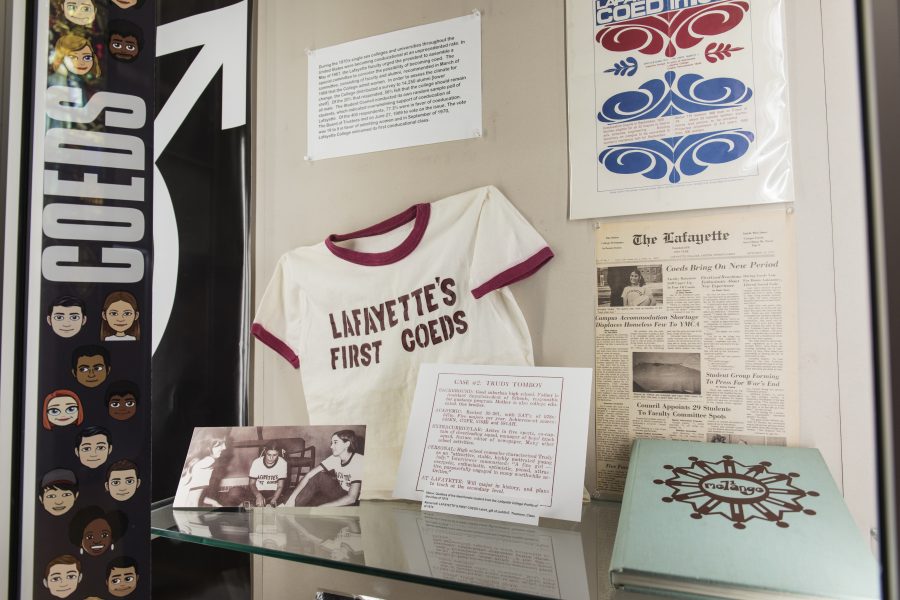

From Lafayette’s first black graduate, David K. McDonogh, to coeducation in the 70s, to the more recent battle LGBTQ+ inclusion on campus, the exhibition at Skillman Library highlights many of the key struggles and successes that Lafayette students have experienced.

Lafayette’s Director of Special Collections and College Archivist Diane Shaw and Associate College Archivist Elaine Stomber assembled the documents for the exhibition, which features stories, photographs and artifacts from different periods in Lafayette’s history.

One particular story was that of Henry L. Baltimore, an enslaved African prince who gained his freedom in 1827 and attended Lafayette in the 1830s, where he was “treated more like a dog than a Christian brother,” according to Shaw.

“[Baltimore] was new to us,” Shaw said. “A scholar who had been studying the African-American student body at Colgate thought [Baltimore] might have some kind of connection to the population at Lafayette. He sent us an email asking to hear more and we had never heard of him.”

Underrepresentation and prejudice against African-American students on campus was a trend that only grew in the ensuing years.

“We have this shameful fact that we didn’t admit an African American student between 1846 and 1947, when we admitted two Tuscany Airmen,” Shaw said. “You’re looking at 138 years without women, 100 years without black students. It was pretty much a white male world for quite a while.”

One salient aspect of the exhibition, however, is the pivotal role that the student body has played historically in demanding equality and combating bigotry on campus.

According to Shaw, one such instance of student solidarity on campus came in 1948.

“Lafayette had a good enough record to have a bid for the Sun Bowl that year. The Sun Bowl was not going to let the halfback, David Showell, play because he was black and the stadium in Texas was segregated.”

“Our students rallied and had a huge demonstration and the college did turn it down for the right reasons. There was even a song written about this, called ‘The Greatest Game We Never Played,’” she added.

The Association of Black Collegians (ABC) was also a powerful force on campus starting in 1969, when they first got together and made a list of demands.

“The students wanted pretty reasonable things: more black students, more black teachers, more courses on black history, a black house. The first thing they got was the black house, right on the quad,” Shaw said. “The association also worked with admissions to make brochures specifically targeted at African-American prospective students.”

However, even after policy changes, the culture on campus was still slow to catch up. Prior to the Title IX act, all of the women’s sports teams had to share jerseys, and only had a varsity division.

In 1993, the Princeton Review named Lafayette College the most homophobic college in the country. In 2009, the college finally saw the first “Diversity and Inclusiveness” statement that outlines Lafayette’s commitment to pursuing diversity and consistently assessing the efficacy of its initiatives.

The exhibition is currently accessible on the first floor of the Skillman library. It is decorated with hundreds of Bitmojis interspersing the photographs and stories from times past. It is meant to be a sweeping reminder of the struggles and successes that have formed Lafayette’s modern student body.

Angela Hughes-Earle • Apr 8, 2018 at 9:01 pm

Correction. It is spelled “Tuskegee Airmen” not “Tuscany Airmen”