Bio Art is an international trend that has grown increasingly popular over recent years. Since first appearing in the late 90s, it has migrated throughout countries, including Singapore, Australia, UK, the Netherlands and Canada, before finally making its way into the curriculum of art schools across America, according to Suzanne Anker.

“[Bio Art] is a subset in the way in which the natural world has been embraced by artists since the Paleolithic times,” Anker said in her presentation this past Tuesday, April 10.

Anker is a pioneer in Bio Art working at the intersection of art and the biological sciences, she said.

She works in a variety of mediums ranging from digital sculpture and installation to large-scale photography to plants grown by LED lights. Her work has been shown both nationally and internationally, including the JP Getty Museum, the Pera Museum in Istanbul and the International Biennial of Contemporary Art of Cartagena de Indias, Colombia.

During her talk, Anker stated that she is trying to learn and discuss collaborative relationships within arts, humanities, science and engineering, and what that might look like at the college. She believes Bio Art is the key to create a framework for these different mediums.

Anker divides Bio Art into three categories: cultural imagination, wetware, which Anker said is biology, and computer processing.

For Anker, these three categories have been used within her own art. She began her presentation by speaking of a project that incorporates the category of wetware. She spoke of a team of scientists who have been working on creating a blue rose using genetically modified plants.

Because high saturation colors like blue are so rare in nature, Anker sees this project as art, not science.

When she was interviewed in the midst of the project, Anker said, “if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t matter because it’s art. I have the supposition that for every scientific discovery, there is a cultural equivalent.”

She cited a survey conducted by the Mars company, which found that one of the most popular colors of M&M’s is blue. She said that creating blue M&M’s is an example of culture going beyond the science, which appeals to her first category of cultural imagination.

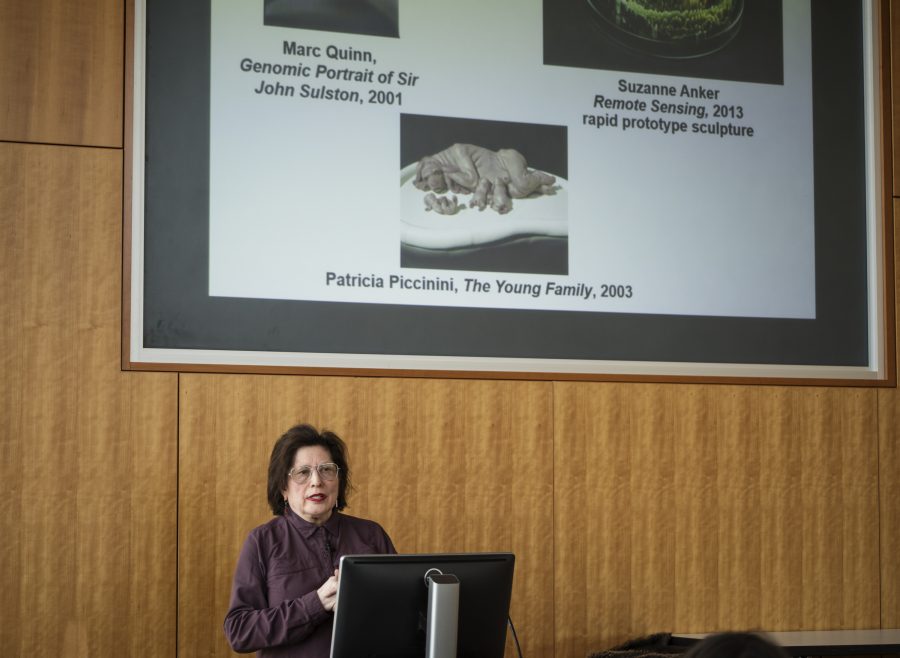

Anker also addressed computer processing. These are original pieces of art created through remote sensing and rapid prototype prints. Anker calls them remote sensing because “they have a topographical presence when you look down on them.”

According to Anker, her projects begin as a photograph before getting converted through a software program into 3D. She uses this technology to combine both the inorganic and organic—from nature and from culture.

“I’m still working on this project, creating a whole new set of these because they’re very exciting to me,” she said.

Not only did she discuss her own work, but Anker also went on to list many other Bio Artists and the work that they are doing. Her examples consisted of Jalila Essaidi’s “Bullet Proof Skin” (2011), in which she used spider silk to try to create bullet-proof skin.

Another project Anker mentioned was Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s “Stranger Visions” in 2013.

Dewey-Hagborg used DNA testing with DNA found on gum and cigarette buds to find out hair color, eye color and the width of the subjects’ lips and nose to construct a likeness of what the subjects would have looked like via computer programming.

Other artists she mentioned included Christina Agapakis, Liora Yuklea, and many more, in addition to scientists such as Alexander Fleming and IFLScience.

She ended by explaining how Bio Art is frequently being used to raise awareness of prevalent biological issues.

She included images with birds drowning in oil or dolphins cut open with nothing but trash pouring out.

“What makes matters worse, and I’m an optimist, is the fact that there’s microplastic in our oceans that you can’t even see,” Anker said. Because of issues like these, Bio Artists are using their talent to raise awareness to major environmental problems.