Twelve years ago, the students of the Lafayette Tech Clinic were given a task by the then-director of the course Dan Bauer: find a better way for students to get downtown. At the time, the college was searching for a use for the buildings on Third Street, which had recently been acquired by the college.

The clinic, an interdisciplinary course that comes up with solutions to real-world problems, subsequently submitted a report to the college outlining what they believed to be the best three ways to get students downtown efficiently. Included in these solutions were a funicular, a vertical elevator and a shuttle.

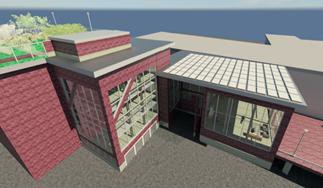

Then this summer, Lafayette officially announced plans to build a vertical elevator from the top of college hill to Easton. The college has applied for a $4 million state grant to fund the $8-9 million project.

After a decade-long hiatus after the first report, the idea came back to the classroom. In the fall of 2014, civil and environmental engineering professors Sean Dooley and Michael McGuire tasked their engineering seniors with finding a better mode of transportation to downtown Easton from campus. It was the objective of their year-long civil and environmental engineering capstone class.

“It looked like these historic stairs might not be cutting it in the long term,” McGuire said. “The shuttle bus might not be the best long term solution. We should think about ways of connecting these two locations.”

The 2014-2015 capstone class voted on further developing the idea of an inclined elevator, or a funicular, over other options that were considered, such as a vertical elevator and restoring the original historic stairs, according to class member and alumnus Stacey-Ann Pearson ’15.

While students focused on other ideas to an extent, the inclined elevator became the main focus of the course, according to Dooley.

The class and the tech clinic also found it to be the least costly option, but as current director of the tech clinic and geology professor Lawrence Malinconico said, they also did not have the same resources as the college does now in 2004.

The capstone class is required to give a presentation at the end of every year describing the progression of their work. Faculty and administration members often attend, according to Mary Wilford-Hunt, the director of facilities planning and construction.

Wilford-Hunt, who attended the capstone presentation in 2015, wrote in an email that their presentation restarted the conversation in the college and added why the college decided to go with the vertical elevator plan.

“Clearly, this work propelled the discussion of better connecting to downtown Easton from initial concept, to potential future implementation,” she wrote.

“The current plan is envisioned as a vertical, rather than an inclined elevator,” she added. “This technology is more commonly found in the U.S., and would result in the loss of fewer trees along the hillside.”

Pearson said that her class did not get their specific idea from the Tech Clinic report, and added that her engineering class did not take credit for coming up with the idea of an elevator going downtown. That idea had long been present among members of the community at Lafayette from the 2004 report.

The professors handed the task on to the next year’s capstone class in fall of 2015 after the previous year’s class worked on it.

Each academic course also discussed other options, and the tech clinic ultimately included two other options in their proposal to the college: a vertical elevator and a shuttle.

Kevin Yell ‘16 was a member of the capstone civil and environmental engineering class last year as a senior. This class continued the work that the previous year’s class had started, and further developed the inclined elevator project, he wrote in an email.

“We focused on the actual elevator system,” he wrote. “In class we mainly discussed … how to get past road bumps we may hit, or did hit, along the way. The class was mainly [an] ‘outside work’ class where the professors provided guidance and assistance and it was up to us to work/communicate with them, as well as the other groups, to achieve the results we wanted.”

Pearson described her class as a memorable experience and as “a simulation as close as one can get to an engineering firm.”

However, Dooley said that he sees the class as much more.

“We do say throughout the year that this isn’t a simulation,” Dooley said. “What they are doing is meaningful.”

“I think for future years, they can refer to this year and know people are really looking at their work, which is good,” he added. “[It’s] a motivator.”

Co-written by Yazmin Baptiste ’20 and Kathryn Kelly ’18.

Peter Crownfield • Sep 26, 2016 at 2:14 pm

If everyone used the steps, it probably wouldn’t make sense to replace people-powered steps with an elevator. I’ve heard some people refer to the steps as a ‘cardiovascular challenge’ challenge, but doctors & health authorities are constantly encouraging people to do more active workouts to promote health.

Due to time constraints, lack of energy, or disabilities, though, many students ride the shuttle buses — and there might be an energy-efficient way to replace them with an elevator. The only way to be sure is to do life-cycle analyses of the elevator and the shuttle buses. Since Lafayette is a signatory to the American College & University Presidents Climate Commitment, the analyses should pay particular attention to greenhouse gas emissions [GHG].

A few key points that need to be covered in these analyses:

• Will the elevator be solar-powered? If so, will it have a suitable storage system so it can operate after dark?

• Will each descent generate energy that can be used to power the next ascent?

• How will the elevator deal with a whole class (or 2) getting out at one time? … with crowds coming to or leaving an event at the theater?

• Will there be emergency backup in case there is a power outage?

A life-cycle analysis must, of course, include the manufacturing and construction process in addition to operating costs.