In recent years the world has seen an increase in populist sentiments and movements, and according to Fareed Zakaria, those sentiments are most likely here to stay. However, as he closed in his talk to the Lafayette community, it is something that can, and needs to be addressed by the current college-aged generation.

“You have a huge job ahead of you,” he said to the audience. “Don’t screw it up.”

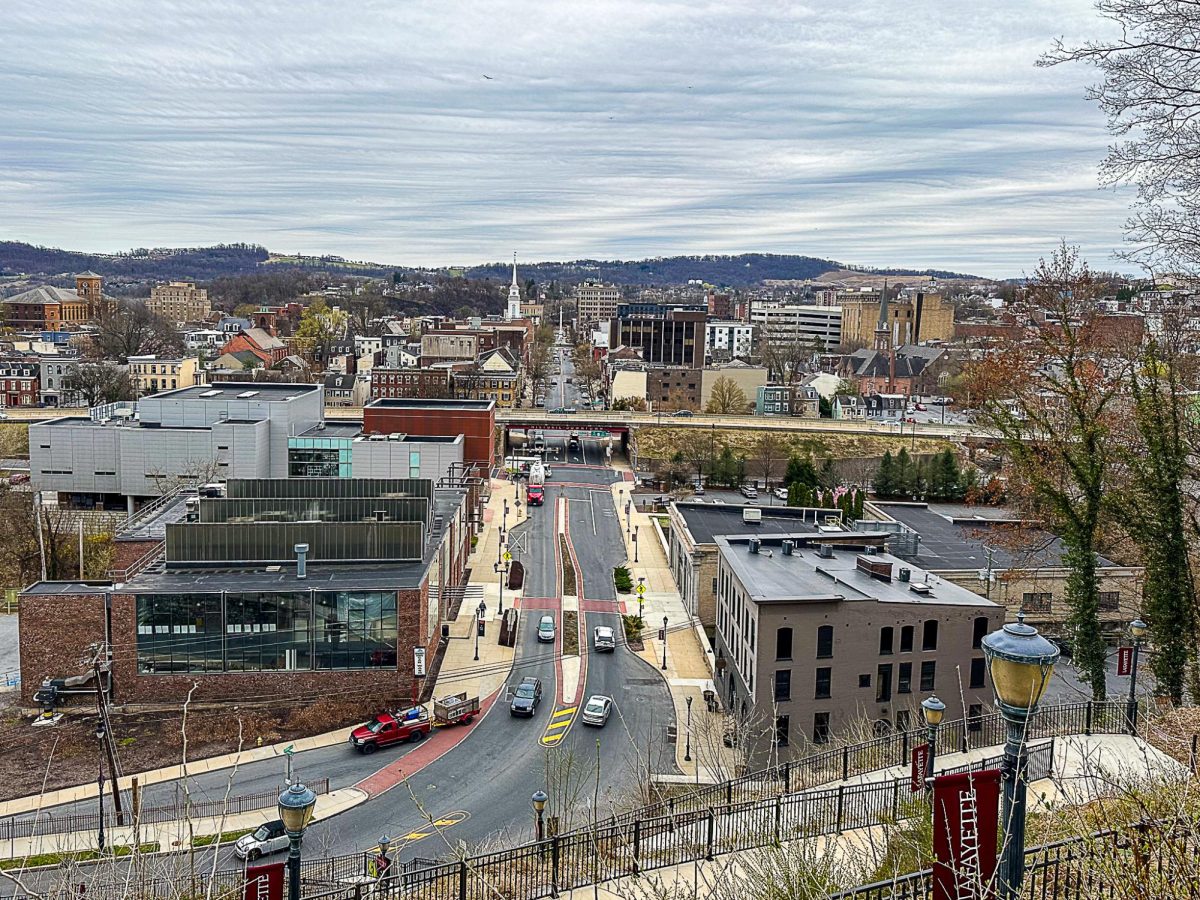

Zakaria, CNN host of Fareed Zakaria GPS, columnist for The Washington Post, contributing editor for The Atlantic, and bestselling author, came to Lafayette last Thursday night as the International Affairs Major’s 60th anniversary speaker. In his talk, Zakaria addressed how the effects of capitalism, culture, class and communication in an age of increased information access, connectivity and movement of people has resulted in the discontent that has fueled populist sentiments and leaders in countries like the United States and Germany.

The Lafayette was able to sit down with Zakaria before his time in Colton Chapel with the campus community for a one-on-one interview to further discuss his view on the upcoming elections, media and education:

The Lafayette: While you mentioned you’re not entirely sure how you feel about impeachment, you did say in a column back in April that the process of impeachment would increase the class resentment between the urban elites and middle-class Americans that had previously fed support for Trump. You also added that while you aren’t sure about impeachment you do believe that it would be best for Democrats to beat Trump through the polls and not through impeachment. So on that whole vein, what do Democratic candidates need to do to overcome these tensions for this election and specifically going into the future for other elections considering these populist sentiments that are redefining what the Republican party looks like in America?

Zakaria: I think the way I think about this, as somebody who is very worried about the rise of Trump, but more importantly the rise of what he represents, America’s support for Trump, and you can see the depth of that support by looking at just all the crazy stuff he’s done and the fact that it doesn’t change the support for him much at all. He’s still about 40% approval which is staggering considering what he’s done that 40% of the American people still support him no matter what. I think you need to ask yourself why, and you have to ask yourself what is the way to address that? And that is what I worry about with impeachment, not that he wasn’t done terrible things, but the way you deal with something like this is you defeat it at the polls, you defeat it by campaigning, you defeat it by presenting other ideas, and hopefully, by defeating him and it at the polls, you kind of discredit and delegitimize these ideas.

I think what Democrats have to do in that quest is to recognize that some of the issues that have animated Trump’s base are real issues. That we have had a huge amount of illegal immigration in this country, and it has rattled people. I think that as a legal immigrant I don’t want to be out there advocating that people come in breaking the laws, violating all the rules of immigration, all the people who have been trying to do it legally and kind of patiently going through the process. I certainly don’t think one should be vindictive and punitive and racist in the way in which one talks or acts with those people, but you know breaking the law is not something we should condone in a society of laws and rights. I think that we have to recognize that even on an issue like some of these cultural issues that they can be a reality that you’re moving so fast that people find it disorienting and as a result there is a backlash. I don’t think one should give in by sacrificing those ideals, you know whether it’s women’s rights or gay rights, but I think that there would be a way to talking about it where you recognize that people had some anxieties or something like that.

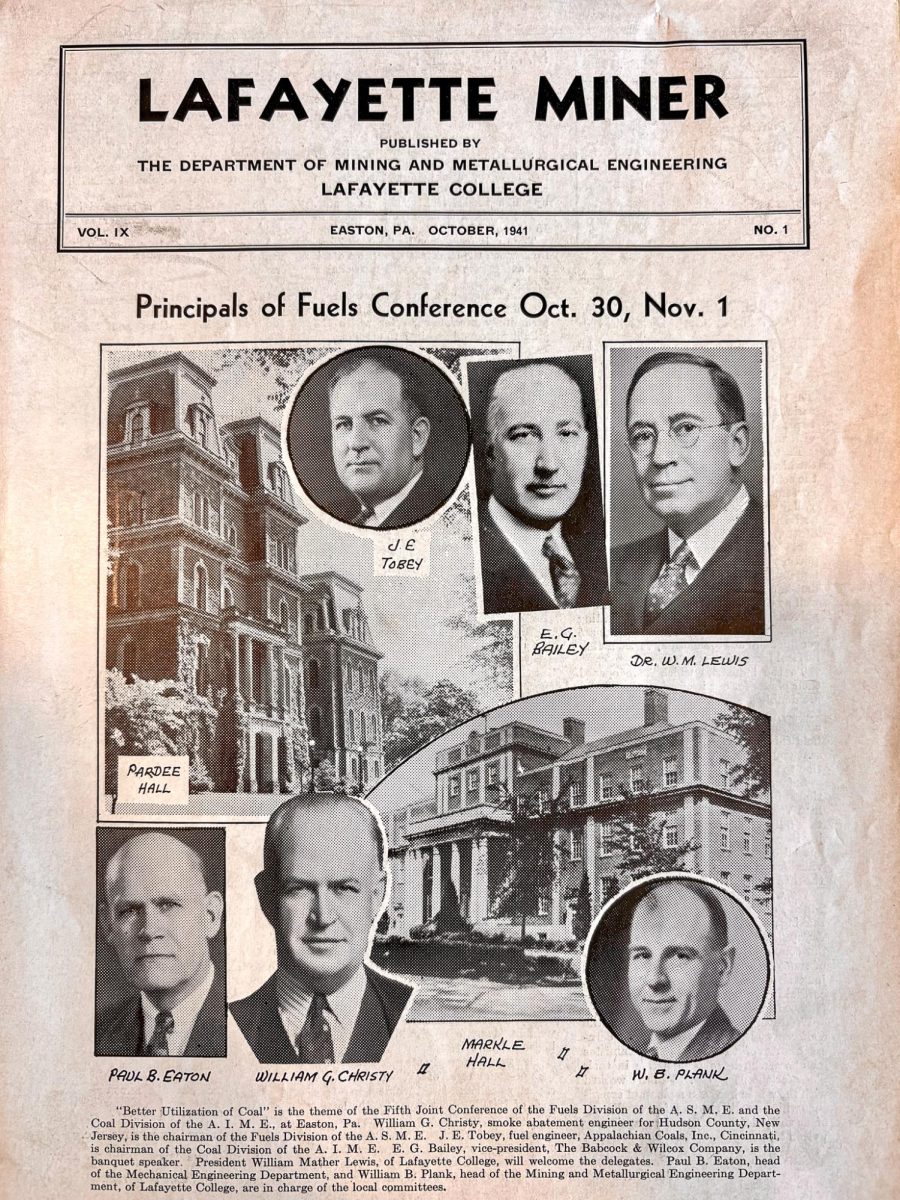

I’ll give you an example, my colleague at CNN Van Jones says, when you talk about Green Jobs and the transformation that you want to affect in America, wouldn’t it be great if President Obama, (and he’s a big supporter of President Obama, he worked for him), had gone to the coal mines and met with the coal miners and said to them ‘You guys are heroes, you have been risking your lives to turn the lights on in America, and we commit to you that we are going to find great jobs and great training for you as we transition so that your children don’t have to go down these mines and risk their lives, and we will find ways to create a new generation of jobs for a new generation of Americans. Something like that. Some of these things are rhetorical ploys or gimmicks of course, but, you know you’re trying to send a signal to people that you respect them. That you honor them. And a lot of what’s going on here I think is a sense of a loss of dignity, a loss of status, a loss of honor. I think that has a lot more to do with it than the pure economic issues that people sometimes talk about like stagnant wages. It’s honor, it’s status, it’s dignity. These are very core things that motivate people.

And do you foresee a Democratic candidate being able to do that this election?

I think so. I mean, I think the question is can they take this to heart? They’re all bright people…very committed people. But the question is, do they really get it? How important this is? Do they understand how disrespected large parts of the country feel? And, can they do it while navigating the very energetic and noisy activist base that is now the Democratic party. We often talk about the Republican party’s base and how people have to pander to it; it’s also true on the Democratic side. There is a kind of pressure to conform, a pressure to gain applause. I’ll tell you, there’s nothing politicians like more than the sense of being in a room and everybody agreeing with them. This is crack-cocaine of being a politician. You’re in a room and you want people to say ‘Hallelujah’ when you speak, and you see that at these debates. By the end of a couple of those debates the Democrats were basically all saying ‘we will not enforce the borders, anyone can come in, and by the way we’re going to provide free healthcare for everyone who comes in.’ That is not a tenable position to say that you’re literally going to let anyone who wants to come across the border into America and then you’re going to provide them with free healthcare and education. But yet, that is the logical process of pandering to these activist bases. We can see it more clearly and condemn it on the Republican side but there some similar dynamics on the Democratic side.

So, more of a foreign policy question. At the U.N. last week, President Trump delivered a very strong, nationalist speech, saying that the future doesn’t belong to ‘globalists,’ but rather to ‘patriots.’ A month before, you commented on how the last defenders of free trade are in Africa. Kind of looking at both these different concepts with President Trump’s rhetoric, how do you foresee Africa’s adoption of free market policies and rise of private businesses, and the increase of Chinese investment into the African continent impacting the US’s role in the political economy?

I think what Trump is doing is terrible with regard to this celebration of nationalism at the expense of international cooperation, internationalism. This has been America’s great project from 1945, to get the world to cooperate more, to build a liberal, international order where people resolve things not through wars and guns but through trade and cooperation. We have benefited massively as a result of it. We have created a world in our image, one that we dominate. And when the President of the United States does this it sets in motion a whole copy-cat phenomenon. It’s not just because of the United States but it’s not an accident that you now have voices of nationalism in Europe, in places like Hungary and Poland, in the Middle East, countries like Turkey, and Asia, countries like India and China. Everybody is now vying to demonstrate how they’re going to put India first, put America first, put China first, but of course this is a recipe for a kind of narrowed horizons, protectionist world in which everyone does worse, everyone is suspicious of one another, and all the biggest and most crucial challenges, like global warming, are now ones that you can’t address because you’ve suddenly discredited and delegitimized the whole idea of global cooperation.

I think that, it has been a terrible turn to see the American president who has long been from both parties the champion of these issues, become the greatest detractor of them.

I think that, however, the point that you make about Africa is very important to keep in mind. The world is going to keep turning, and globalization in many ways is going to continue because it is a path for growth, it is path for dynamism, it is a path for countries to find their way out of poverty, and those who are able to embrace and use it to their advantage, like the Chinese, will benefit. But the United States turning its back on global cooperation, it will only mean we will set the agenda less. Our interests will be less at the center of the world, and we will suffer economically. If we had signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, if we were more active, we would do better as an economy. The simplest way to think about it is, for the last 75 years, we’ve done all these things that Donald Trump now says are so horrible. We have become the richest, most powerful country in the history of the world. This is not an accident, these two events are correlated, these two trends. It is precisely America’s embrace of internationalism that has allowed it to be the dominant economic, political, technological, cultural force in the world.

Going off of that with speaking to globalization and kind of the media, we were speaking of the information revolution and how we’re kind of ‘drinking from this fire hose that we can’t filter.’ With that in mind, in reference to what you referred to as ‘Illiberal Democracies,’ to what degree do you feel that social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have resulted in, more or less, a false sense of knowledge about the activities of those who exercise real power, and what can be done to combat this?

So on the one hand, I do think it is useful that politicians have kind of a direct mechanism through which to communicate, and I think that’s just part of the Democratization of information that has taken place. It has its bad sides, but I think on the whole it’s been a useful thing, people can figure out immediately what somebody thinks and what somebody else’s response to it is because of social media. I think the mistake that people make is to think that that is the end of the pursuit of knowledge or information. That actually, people were dissembling when they would make fancy speeches in front of big podiums and they are often dissembling when they post on Twitter. The challenge, finding information and finding the facts is really hard, and it’s actually harder now because you have this plethora of noise, from the middle of the noise you have to find the signal, you have to find the facts and real information. I think that’s why there is a real value in having excellent journalism, independent journalism, very good scholarship, having people who are genuine experts.

I think we are living in an age where there is a tendency for everybody to think they’re an expert about everything, to decry the value of expertise. I think actually it’s exactly the opposite. It’s precisely in a world like this where you need expertise more than ever because there’s just so much noise. It’s all just as a result a kind of, William James once called it a ‘blooming, buzzing confusion,’ and if you have that blooming, buzzing confusion, what you need are some gatekeepers, some people who you can trust, some places that do real hard work of fact-finding and investigation and genuine scholarship. So that’s the problem. The platforms that social media provides have all kinds of advantages, but it’s weirdly naive to believe that just because you have Twitter, or just because you have Facebook, or just because you have Google, you’ve suddenly become a kind of master, or that everyone is now an expert on everything.

And one last question, I think, that would be interesting for students at Lafayette to hear, more particular to your recent book ‘In Defense of a Liberal Education,’ and because Lafayette is a liberal arts institution, what advice would you have for Lafayette, considering they have recently added a new Bachelor of Science degree in Engineering Studies, a new data science minor, they recently built a new integrated sciences center, so kind of with this perceived notion of a focus on STEM and the sciences, what advice would you have for its future approach to maintaining and growing a focus on critical thinking, communication and the historical roots of a liberal arts education?

I think it’s very good that Lafayette is doing this, because I think that what people sometimes forgot, and educators forgot in sort of the last 30 or 40 years is that the liberal arts in its origin was never thought to be something opposed to science. In its historical origin the term actually means arts as opposed to crafts, as opposed to very narrow, trade-based education. The arts was meant to be more an exploration of knowledge, so when the original liberal arts curriculum, which all date back to ancient Greece, 50% of it was science, it was mathematics, it was geometry, it was astronomy, it was things like that. And then there were things like rhetoric and history as well. So in a way, I think Lafayette is kind of returning to that more balanced view of a liberal arts education.

I think that really, what you want to do is to feel like you are conversant in both elements: the sciences and the humanities, or the sciences and the humanities and the social sciences, if you want to think of it as a tripartite division. What that kind of breadth gives you is flexibility, adaptability, curiosity and growth. There’s a wonderful piece in the New York Times reporting on a new big survey just last week that pointed out that everyone obsesses about the fact that STEM graduates earn more money than liberal arts majors, and what it found was that’s true for the first five to seven years. After that, the gap vanishes and liberal arts majors actually do better. And it makes perfect sense, because you start out, you have a very narrow skill that you’re being used for, and as you become more senior in the organization, as you stay longer, as your jobs change, you start requiring a more broad view, a more interdisciplinary view. Suddenly your judgment, your ability to put things in context, your ability to work with people starts to come into play, and all those skills are often ones that the liberal arts majors have even more strongly.

Ideally, as I say, you’re conversant in both, but I don’t think people should worry too much about what they major in. What they should worry about is, are they taking hard courses, are they doing well at them, you know you’re at a place like Lafayette, one of the great, great educations in the world, are you taking advantage of that fact in a way that you won’t regret later on, in a way that really fully exercises your talents and skills. That’s the really important thing. Whether you major in English or economics, it really doesn’t matter. The truth is 10 years out you’re going to be doing something very different, what will remain are the essential skills of problem solving, of working, of curiosity, of the ability to work with teams. Those are the core things that people care about.