Imagine an elite country club in which all of the staff members are black and very few of the guests are black. Two wealthy white women mistake one of the black guests for a member of the staff. Though it was not a “straightforward” mistake, professor Rima Basu of the Claremont McKenna philosophy department urges everyone to “consider the moral implications” as the action was a “paradigmatically racist thing to do.”

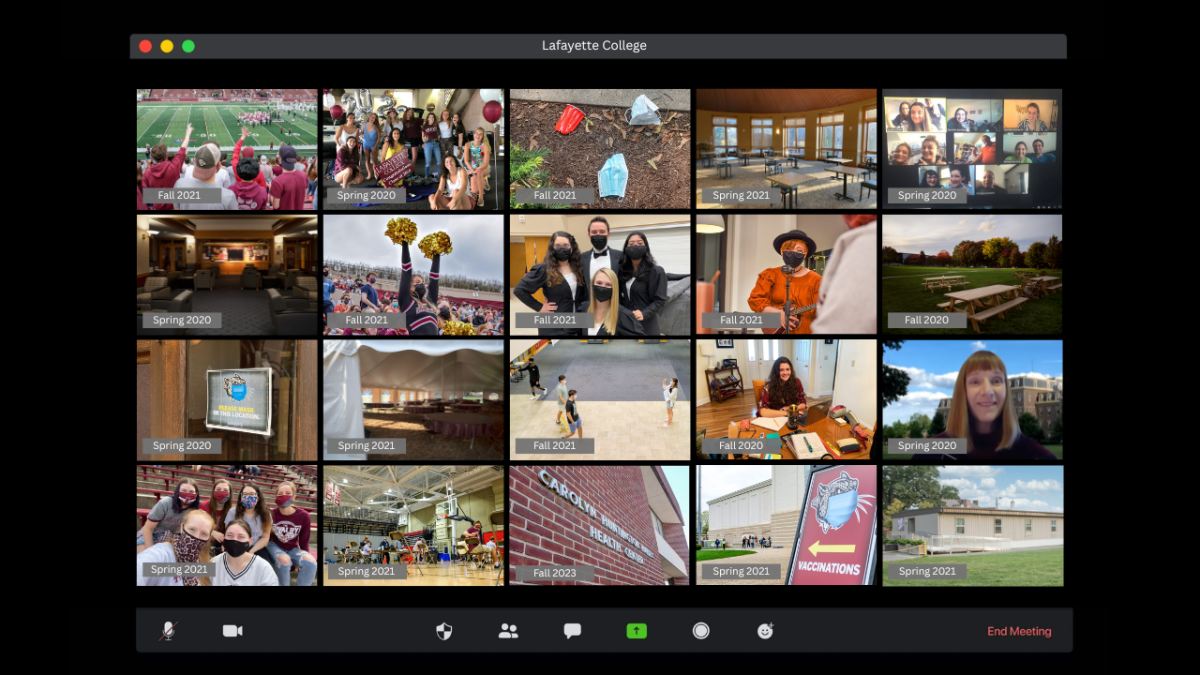

In the midst of a highly controversial election season, a historic pandemic, nationwide protests against racial injustice and a number of other present-day situations involving morality, questions of moral behavior and self-conduct in relation to the greater world have gained new prominence. Basu and philosophy professor Joseph Shieber convened over Zoom to address some of these questions and present Shieber’s paper, “Divorcing Doxastic and Epistemic Obligation,” and Basu’s paper, “A Tale of Two Doctrines: Moral Encroachment and Doxastic Wronging” to an audience of Lafayette students and faculty on Thursday.

Basu presented the country club example to illustrate in tandem the two main doctrines in their paper: doxastic wronging and moral encroachment.

Basu explained that moral encroachment means that “moral considerations earn the question of whether a belief is justified.” While some critics argue that justification can only be based in knowledge alone, or epistemic, Basu stressed the point that, because some beliefs can be better or worse than others, morality is an important component in justifying a belief.

In other words, “When it comes to what we should believe, morality’s got some bite.”

Doxastic wronging also examines the bearing of knowledge on belief, but is still distinct from moral encroachment, Basu said.

“[Doxastic wronging] is the thesis that it’s our beliefs that…themselves are the sources of wrongdoings, regardless of whether our beliefs are expressed in our actions,” they explained.

Specifically regarding doxastic wronging, Basu presented the idea that the “source of moral wrongdoing” is more hurtful to others than the wrongdoing itself. Additionally, Basu described a theory regarding posing special responsibility surrounding beliefs about one’s friends and loved ones, suggesting that this distinction may cause a person to engage in doxastic partiality and to “accept doxastic wronging and reject moral encroachment.”

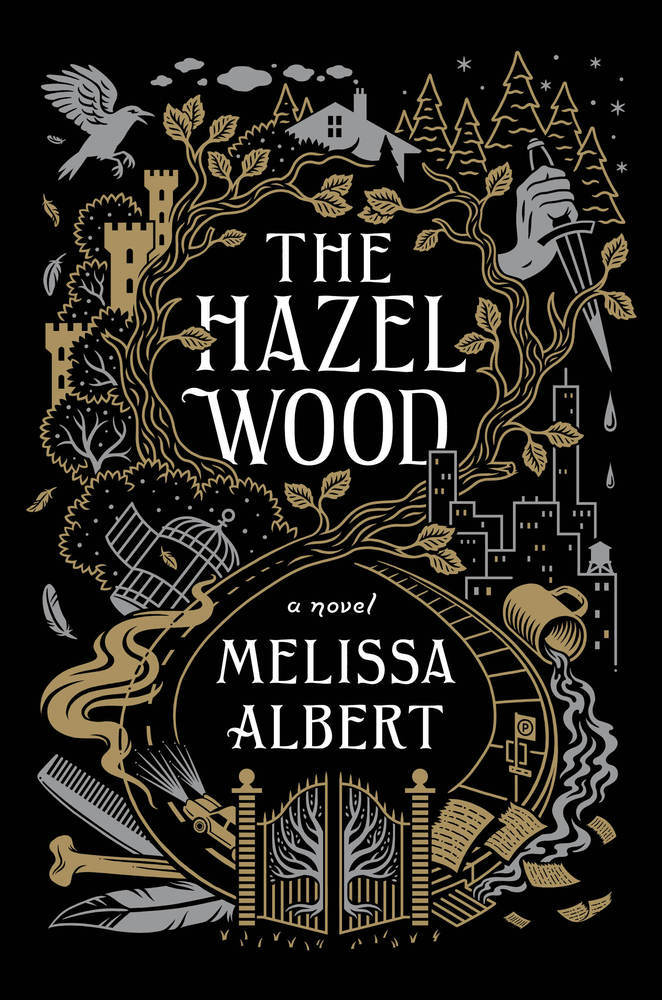

In the second section of the lecture, Shieber began by describing two possible interpretations for famous literary figure Don Quixote. The first was an ironic reading that satirizes the characters’ knightly tales and the second was a romantic reading in which Quixote is perceived to be a heroic figure who transforms his ordinary life through solely his imagination.

Of the latter, Shieber said, “If it’s a possible reading, then it strikes me as legitimate to judge the value of beliefs according to criteria other than purely veristic or epistemic ones…Don Quixote is heroic because he doesn’t believe the world as it actually is.”

Going off of this idea, Shieber insisted that it is legitimate to also judge values of beliefs of all kinds on more than just these two criteria.

Shieber then used this concept to debunk epistemic obligation, which equates individuals’ beliefs solely with their views of the real world. Using the Don Quixote example, Shieber explained his idea that this view is too narrow and excludes fictional worlds and worlds that do not exist. In addition, he referenced Italian novelist Elena Ferrante and the notion that beliefs can be based upon lies we tell ourselves.

Shiebers’ proposed solution was to “divorce doxastic and epistemic obligation.” This entails expanding the causes of why beliefs exist, as “there might be other sorts of obligations that are governing belief that are not epistemic reasons.”

Shieber concluded his talk by emphasizing the “obligation to avoid bringing about situations that one believes will harm others” and that beliefs have real world consequences, especially regarding implicit bias and particularly in the case of legal prosecution.

The question and answer portion of this discussion began with a participant asking Basu if doxastic wrong needs to be directed, voiced or shared. They responded by clarifying that directed means “a belief about a specific individual” and that “those are the cases where we get the strongest intuition that there is someone who has been wronged.”

When asked how much control we have over our beliefs, Basu answered that we “can do indirect stuff to control beliefs and I think that indirect agency of our own beliefs is all that we need to be held responsible for them.”

Correction 09/18/2020: This article originally stated that the paper written by Basu was “Divorcing Doxastic Wronging and Epistemic Obligation.” That paper was written by Shieber. Basu’s paper is titled “A Tale of Two Doctrines: Moral Encroachment and Doxastic Wronging.”

jettie h. van den Boom • Sep 28, 2020 at 8:56 am

L.S. Ever thought that Don Quixote is about an initiation; the way the Knight is going on the esoteric path ..the three passes as in Parzival. ou can read the DQ also in three levels.. entertainment- education- esoteric.

Joseph Shieber • Sep 18, 2020 at 12:20 pm

Many thanks to Lisa Green for her lively summary of the workshop featuring Professor Basu’s and my work. I did want to offer one small correction: my (Shieber’s) paper was “Divorcing Doxastic and Epistemic Obligation”, while Professor Basu’s paper was, if memory serves, “A Tale of Two Doctrines: Moral Encroachment and Doxastic Wronging”.