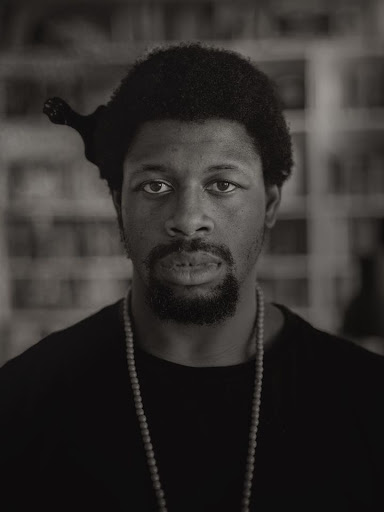

For philosopher Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, reexamining how individuals display emotion can help re-imagine male socialization as a resource rather than an impediment.

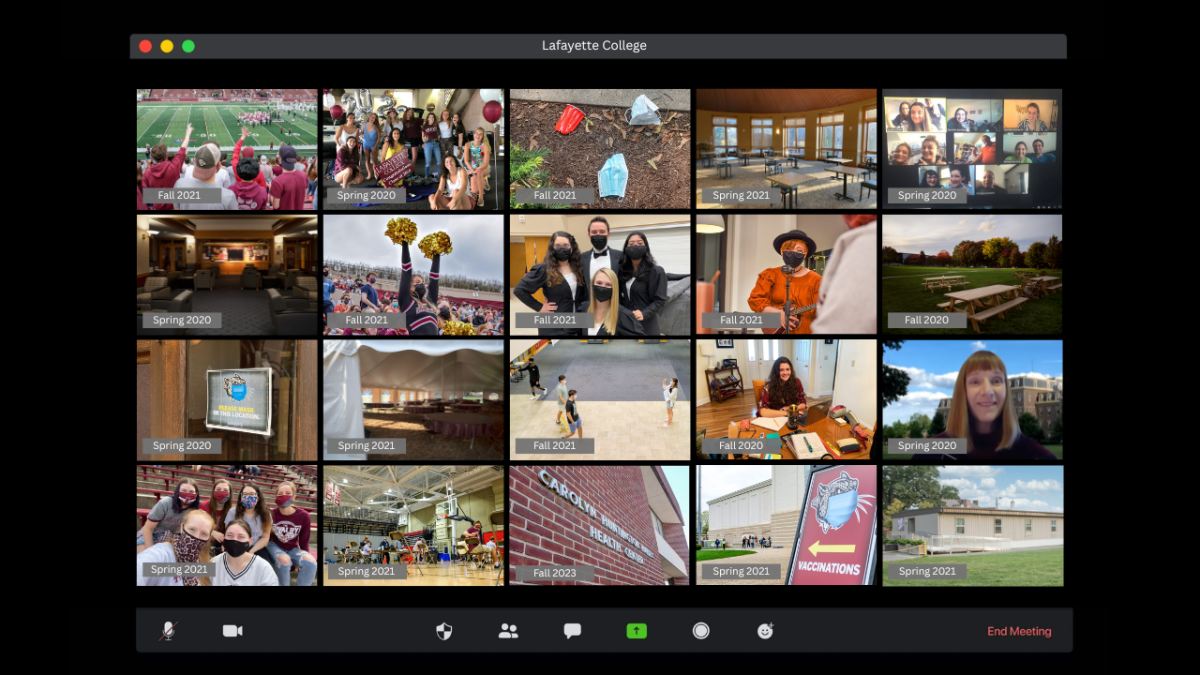

On Thursday afternoon, over 40 students and professors gathered over Zoom to attend a lecture about emotional labor led by Táíwò, a philosophy professor at Georgetown University.

Táíwò is currently writing a book called “Reconsidering Reparations” and has covered myriad topics within philosophy such as environmental justice, climate justice, propaganda, police brutality, socio-economic class and intersectionality.

This lecture featured Táíwò’s paper “Stoicism (as Emotional Compression) Is Emotional Labor.”

He began by explaining the origin of this project. After exploring many leftist and feminist texts in his college years, Táíwò began to examine “masculinity or social structures that produce masculinity or that produce kinds of oppression.”

He explained that the main question of his work in regard to these social inequities between genders is, “Where [do] you want to end up…what do we do now?”

Táíwò said the lens of emotional labor is useful in exploring the concept of masculinity. After conducting a lot of research, he said he came to the conclusion that many things directed towards “male-identifying people” are harmful to them and to society.

Táíwò focused on the notion of men being told to tone down their emotions, and how suppressing emotions other than anger is thought to be masculine.

“There certainly is a problem in the status quo,” he said.

“How you display your emotions needn’t come with this other baggage of not talking about what it is that you feel,” Táíwò added.

He then went on to explain that the two factors that prohibit emotional expression are emotional unavailability and a lack of self-knowledge.

In addition, Táíwò stated that the way individuals express emotion affects others and affects “how a collective that you might fit into deals with them.” In other words, if a person around you is anxious but you show them your sense of calm, they will calm down in response. His idea is that this exchange is valuable.

Táíwò brought these two claims together by explaining that restricting how you show emotion while extending how well you know yourself and how you communicate can be beneficial.

Furthermore, he encouraged building up “self-knowledge and emotional self-awareness” regardless of your gender identity.

One participant asked, given the current concept of masculinity, “How do we motivate people to learn?”

Táíwò’s response was that this problem needed to be addressed from a systemic perspective and that wage labor must be increased in order for emotional labor to be fixed.

Another participant wondered if there were “necessarily negatives to emotional compression” and if it was “better to not socialize boys, in particular, to emotionally compress to begin with.”

Táíwò answered that the issue is more complex than that.

“It’s not just attitudes that we have, irrespective of how the world responds to us, including people that aren’t politically on our team, including institutions that were built according to the attitudes of people centuries ago, according to the availability of resources for different sorts of things, I just don’t see all that changing overnight,” Táíwò said.