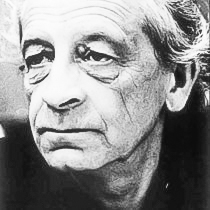

Tel-Aviv University Philosophy Professor Ilit Ferber brought the work of Holocaust survivor Jean Améry to light at the college last Friday. The lecture, in recognition of Holocaust Remembrance Day on April 8, pondered the question of forgiveness in Améry’s work.

“For [Améry], it is both a necessity and an impossibility to be a Jew,” Ferber said.

The discussion was moderated by Government and Law Professor Ilan Peleg and German Professor Dennis Johannβen.

Peleg described the Holocaust as “the most horrific, brutal and inhumane event of the 20th century—millions of people, men, women and children were murdered, not because of what they did, what they said, or even what they believe…[but] for who they were.”

Ferber began her lecture by summarizing Améry’s life as a whole. He was born to a Catholic mother and Jewish father who died when Améry was very young. As a result, he was raised almost entirely in Catholicism. In fact, he only realized that his Judaism was a part of his identity when he read an article about the Nuremberg Laws and realized they would apply to him.

Though he fled Austria in the face of the annexation, he was soon imprisoned in a concentration camp in France. After escaping again and joining the resistance, he was sent to another prison by the Gestapo and brutally tortured. Then, he was sent to both Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, where more physical and emotional torment took place. After the Holocaust, he worked as a journalist and novelist, winning several literary accolades and never once mentioning his experience as a survivor for two decades.

The Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials in 1964 inspired him to break his silence and produce five radio segments about his life as a survivor. He then wrote a book chronicling his experiences within the concentration camps, as well as the torture he underwent and the resulting resentment he felt toward his torturers for the duration of his life.

Ferber unpacked why Améry had decided to break his silence, explaining that this decision was “a resolution that had to do with the world itself, or what had become of it…a decision to face the world that had in time and one might say in haste, moving forward with a disturbing mixture of forgetfulness and indifference, but also with a decisive unwillingness to continue to bear the events of its past.”

She described his tone as a “voice of understatement,” and said the thesis of his essays was to “defend resentment, which he takes to be a feeling of the highest moral value.”

Resentment, she argued, brought clarity to a situation that would be otherwise impossible to understand. She noted that “after the 12 years of the Holocaust…the word itself was distorted, twisted…it is only now that the logic of resentment can make sense can provide us with a truthful, honest, even if uncomfortable stance to take.”

In addition, Ferber stressed the idea that resentment can make the past relevant to people living in the present. She noted that Améry always tried to make his experiences universal and have people relate, because tragedies like the Holocaust impact every human being, not just the lives lost.

Another element of the importance of resentment is ensuring that every event that took place is remembered.

“For him, your rights, nothing, is resolved. No conflict is ever settled. No remembering has become mere memory,” Ferber said.

She then reframed resentment from its typical connotations of grief and anger into an emotion that could be used to fuel a better future. In that vein, when Améry read his essays aloud to a young crowd in Germany, he explained that by sharing stories like his own and keeping that resentment alive, the future could be a brighter one.

“Nothing will ever again, be the way it once was. Possibly, it will be said someday, that the history of a more humane humanity began amid the inhumanity of the ghetto,” Améry concluded in that speech.

After the lecture, one participant asked how Améry might respond to the movement in Germany to ban Mein Kampf. In response, Ferber warned that censoring this text would do more harm than good, stating, “I think that it is problematic to ban something that could be discussed, it should be something that’s part of public discourse.”

Another participant asked how Améry’s perspective could be applied to the growing anti-Semitism present in Germany today. She answered by emphasizing the importance of acknowledging every type of anti-Semitism, on both sides of the political spectrum. She explained that during his lifetime, Améry believed that anti-Zionist movements in Germany was the new form of anti-Semetism, and, if not spoken out against, could have dangerous consequences.