Op-Ed: Ukrainians are fluent in the language of protest, but the fight belongs to all of us

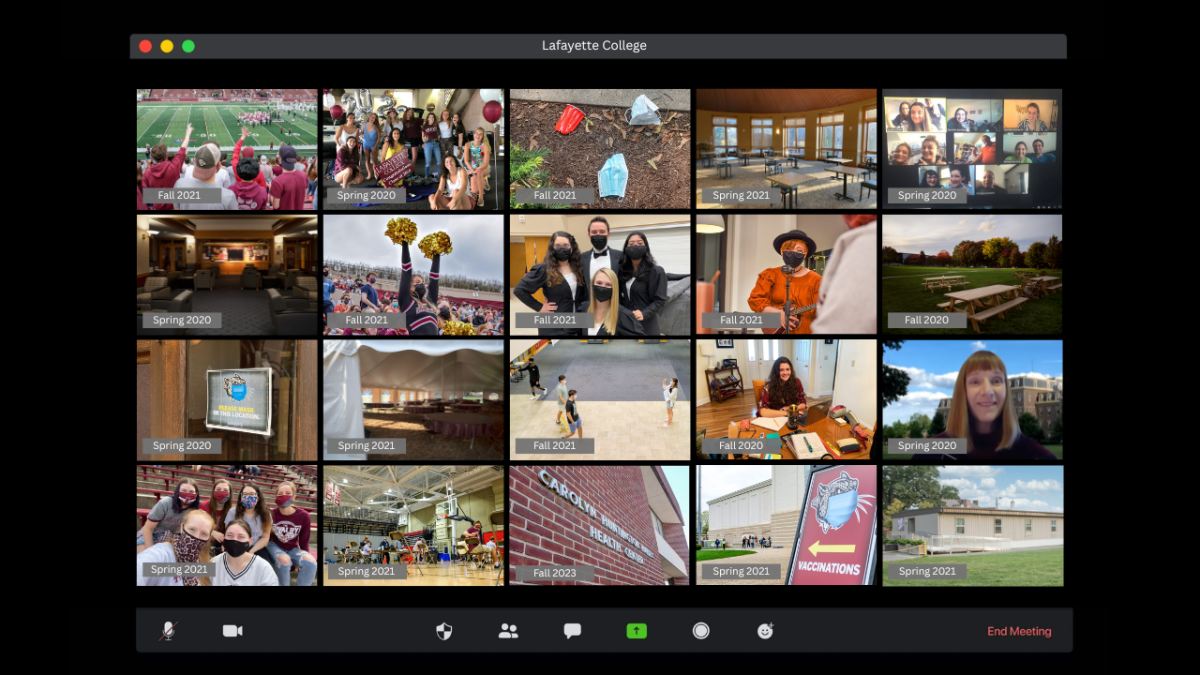

Generations of Ukrainian-American women protesting for Ukraine. Adriana Tymchenko (top left) and Renata Hanchuk (top right) above their respective daughters forty years later, Ksenia Tymchenko ’25 (bottom left) and Deanna Hanchuk ’22 (bottom right).

March 4, 2022

“American with borscht in my veins.”

My six-word memoir, written in 10th grade, hangs on an embroidered hoop in my dorm room here on campus. My Busia taught me to sew in this traditionally Ukrainian style as a young girl. My Baba taught me how to make traditional beet and cabbage borscht. And this message, this identity of mine, has never felt more tattered and beaten than it does right now. I am appalled at the unprovoked and intentional war that is killing innocent citizens of my motherland. I am numb.

I am four years old. One of my first memories is sitting criss-cross applesauce on the carpet of my Ukrainian Montessori pre-school. My teacher, Pani Olenka, gestures to the pictures on the wall of downtown Kyiv glowing orange. We’ve been wearing orange every day for weeks. In January we learn that the peaceful protests have worked. The rightfully elected president, Viktor Yuschenko, is sworn into office as a sour Kremlin-backed Viktor Yanokovych is pushed out of the limelight for a few years. A victory for democracy in Ukraine.

I am 13 years old. My Ukrainian school grammar teacher, Pani Olya, sobs during class. We watch videos of peaceful protests in Maidan turn violent, as (at the time, President) Yanokovych sends in the special police force Berkut to silence those protesting against him. The Heavenly Hundred lose their lives in the fight for European alignment. Yanokovych flees to Russia in the middle of the night and a pro-democratic, pro-European Poroshenko is elected president of Ukraine shortly thereafter. Although the protests end, Putin’s troops fabricate reasons to enter the country and annex Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine. Ukrainian-Americans protest in the streets. War begins in Ukraine, but falls to the back-burner of the international zeitgeist.

I am 22 years old. I sit in my seat in the newsroom when the texts start flooding in. Did you hear? Other editors in the room begin getting notifications and slowly look in my direction. I knew this day would come again. The realist in me knew that the war on the border would spread. My cousin Ksenia Tymchenko ‘25 and I stay up all night watching the news. We pray our family is safe. And we cry.

If you know one Ukrainian-American, you know us all. We are a passionate and involved people, raised to strive for making positive change in our respective communities. We lead, we speak, we serve and we teach. We spend our Saturdays in Ukrainian school, often complaining about literature and geography homework. We see each other in church or at scouting meetings at the Ukrainian center. We learn and perform traditional Ukrainian folk dances at festivals all over the country. We spend our summers at Ukrainian scouting camps and dance camps, and celebrate Ukrainian independence together in Wildwood every year. We also, frankly, never shut up about being Ukrainian.

But besides speaking Ukrainian, we are fluent in the language of protest. Ukrainian patriotism is unmatched. All four of my grandparents fled Ukraine during World War II, threatened to be killed or sent to Siberia for their public love of Ukrainian culture. They each struggled in their own right, fighting a fight for a deep history and a vibrant culture they didn’t want to lose. My parents were born in America but grew up in the Ukrainian diaspora. They fought and protested against individual civil rights abuses of Ukrainian artists and political prisoners growing up, making their voices heard while their motherland sat trapped under the Soviets.

I am a second-generation born Ukrainian-American, yet the fight for my nation and culture is still ingrained within me. My best friends, classmates and scouting peers all come from different immigration waves–some before World War I, others after each of the World Wars, and even others after the fall of the Soviet Union–but we all stand together as one Ukrainian-American community. We speak Ukrainian, we sing in Ukrainian and we mourn together in Ukrainian.

For many of us, this fight isn’t so new. Ukrainian people have been fighting this fight for most of their existence, against one oppressor or another. Now that our fight has taken center stage once more, I feel obligated to stress that this should not just be a Ukrainian fight. Just because the threat of nuclear war looms over our heads now does not mean Ukraine’s fight, and all other fights against tyrannical oppressors, belongs solely to the oppressed. The erasure of any culture is inexcusable and sinful. We cannot let Ukrainian nationhood disappear.

The first European civilization, the Trypillia, finds its roots on Ukrainian land. We are Europe. We are Kyivan Rus. We are the Zaporozhian Sich and the Cossacks of the Black Sea. Our history and culture is extraordinary, and we aren’t going anywhere. Stay educated, keep donating and pray for peace in Ukraine. Slava Ukraini, and Heroyem Slava.

For more information or places to donate, visit linktr.ee/RazomForUkraine or helpsaveukraine.com.