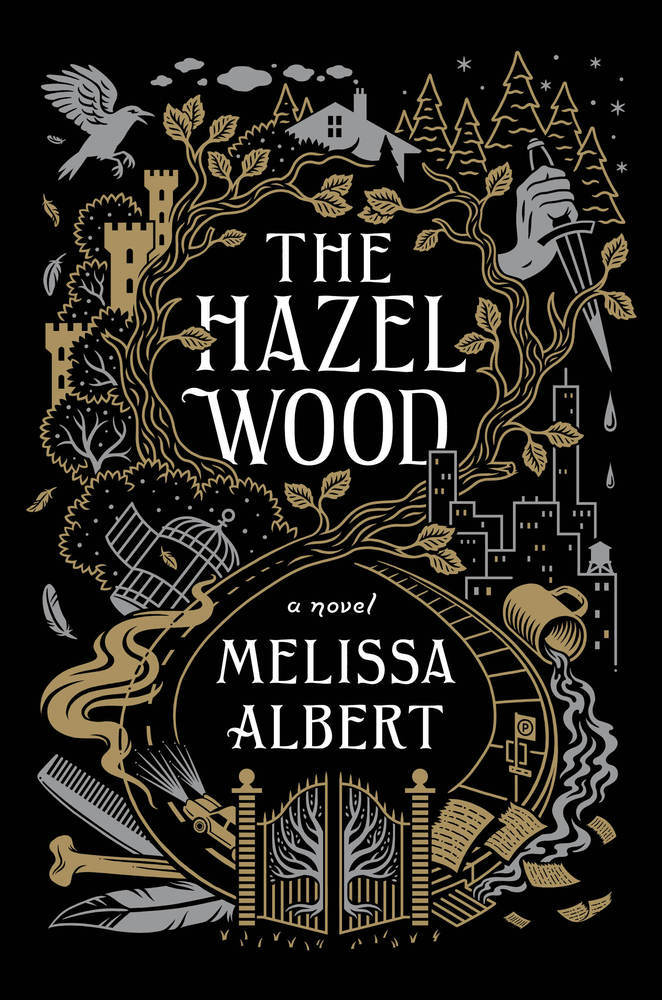

Picture Ted Bundy in your mind. Are you thinking of Zac Efron? Mark Harmon? He’s handsome, isn’t he? Clever and cunning? Jessica Knell will convince you otherwise in her third novel “Bright Young Women,” a fictional account of the very real aftermath of Bundy’s string of murders in the 1970s.

Knell’s thesis, brought to light by her protagonist Pamela Schumacher as she works in dual timelines to get justice after the brutal murder of her best friend and sorority sister, contends that Bundy and other serial killers like him were nothing special — they were men of average intelligence enabled by inept police departments and glorified by the media.

The story follows Pamela, president of her sorority at Florida State University, as she navigates life after coming face to face with the murderer who kills two of her sorority sisters and maims two more. She joins forces with Tina Cannon, a mysterious woman with questionable motivations who is sure the same man killed her girlfriend, Ruth, four years prior.

What the pair uncovers is a pattern of murders that can be traced across the country through repeated escapes from custody, media outlets looking for a cash grab and police ignorance.

This story was riveting — the dual timelines, which countdown to two murders, provide an eerie sense of urgency and I found myself huddling under the covers with my book light on to finish the last 100 pages.

There are certainly scenes of graphic violence against women throughout the novel, but it never feels gratuitous. Instead, readers get the sense that Knell is telling you it is important that you know exactly what happened to these women — it’s grounded in truth, after all.

Knell crafts a story web that is complex and delicate, with the protagonists often offering glimpses into their future perspectives or events that haven’t yet occurred in the original timeline. These function mostly as easter eggs for Pamela’s story, giving the reader just enough information to make me want to read to the next chapter from their perspective.

Most of the time, this works very well for Knell, connecting the two stories and bringing narrative points together across decades. Sometimes, though, it muddies the waters — it’s difficult to be sufficiently horrified when I’m playing Sherlock Holmes alongside Pamela, wondering if each sentence was one I would need to remember for the end to make sense. When you weave as many threads into the story as Knell does, some of them are bound to fall by the wayside.

Knell gave herself a tough job in “Bright Young Women,” which seeks to make readers think critically about the true crime sensation that has become ubiquitous over the last decade. She hits the nail on the head with so much of what has been difficult to articulate about my unease with the genre and provides the satisfying feminist critique I’ve been craving.