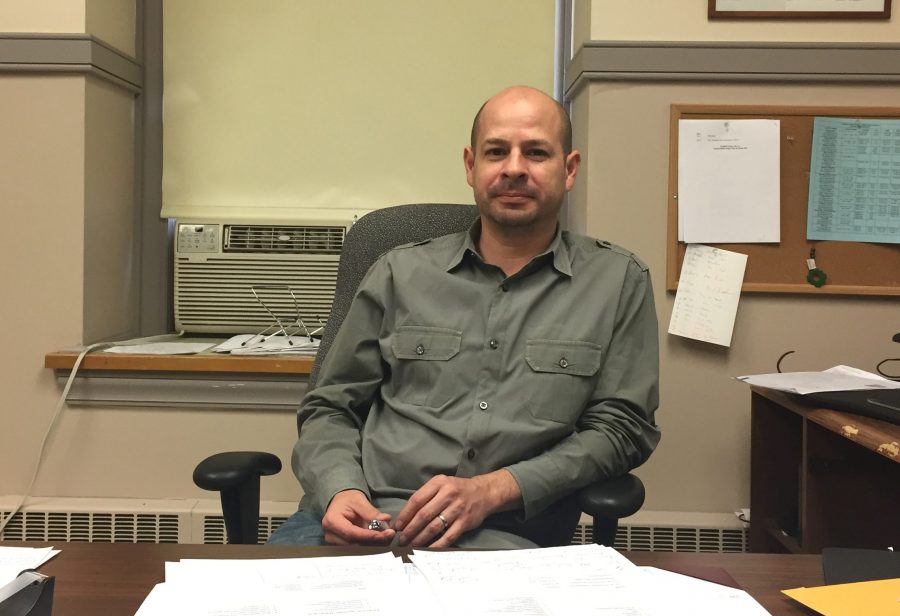

As classes wind down at the end of the semester, Spanish professor Juan Rojo faces the end of his career at Lafayette College.

At the beginning of the academic year, he attempted to push the college to let him stay. Rojo’s hunger strike after he was denied tenure made national news. It lasted six days, ending without his demands about tenure being met.

Rojo was denied tenure when President Alison Byerly disagreed with the decision of two faculty committees nearly unanimously voting to grant it to him. She cited negative student evaluations as her reasoning in a letter to him. He was denied tenure a final time at the end of September.

But even before he began the hunger strike, Rojo said he “never expected it to work.”

“I told my wife before the whole thing started, ‘This is not going to work,’” he said. “But there were a number of colleagues that approached me before, and they were afraid [of asking questions about the tenure process]. And I thought, ‘I need to do something, because I’m the only one that’s already gone through this and has nothing left to lose.’”

Since his strike, the tenure process has been more of a prominent issue on campus. An ad hoc committee was formed to change the faculty handbook’s section on tenure. In Tuesday’s faculty meeting, altering the tenure process was discussed, some motions were passed, but talk about changes is to be continued in their next meeting later this month.

Rojo said he has largely removed himself from these debates, since he is not returning to the college. It is up to the faculty members who will be affected by the changes, he said, but he is “glad the conversation’s being had.”

Right now, he is still looking for a job. He said he is searching in academia, study abroad and translation. Rojo has a wife who works at home and has a part-time job, a five-year-old son and a teenage daughter. For the next few years, he said he hopes to stay at his home in Hellertown.

Some academic institutions have called him back for jobs, but he did not get any further in the hiring process. Still, he said he was “genuinely shocked” any academic institution considered him after his hunger strike, since he thought he would be perceived as a “malcontent.”

Many of his books are gone from his shelves, and there are cardboard boxes in his office for his things. Among what’s not packed are the two Perrier pink grapefruit drinks Byerly gave him the night they met last year, two days into Rojo’s hunger strike. They sit unopened on his bookshelf.

“It’s one of the things…that I didn’t pack yet, precisely because I don’t know what I want to do with it,” he said.

In an earlier interview when he was on his hunger strike, Rojo said he would “be glad to drink one with her when this is all done.” He said on Wednesday that he still has no reason to drink them.

After his tenure case and the hunger strike was concluded, Rojo said the administration reached out and asked if it could do anything to make his transition to a new career easier. He met with them twice, he said, but it was “very difficult” for him to sit down with “people who ultimately made the decision to terminate…my employment.”

In the coming months, he said he looks forward to doing more research. But Rojo said it is difficult to not have any set plans.

“That’s probably the most trying aspect of all this,” he said.