The realities and consequences of anti-Black racism have taken center stage over the last few months. Black Lives Matter protests, company rebrandings, and recent strikes from professional sports leagues, sparked by multiple instances of deadly police violence toward Black people captured on video, have led to a summer of unease and unrest, leaving many to wonder what the next step should be. For many, that first step toward a more anti-racist future is conversation.

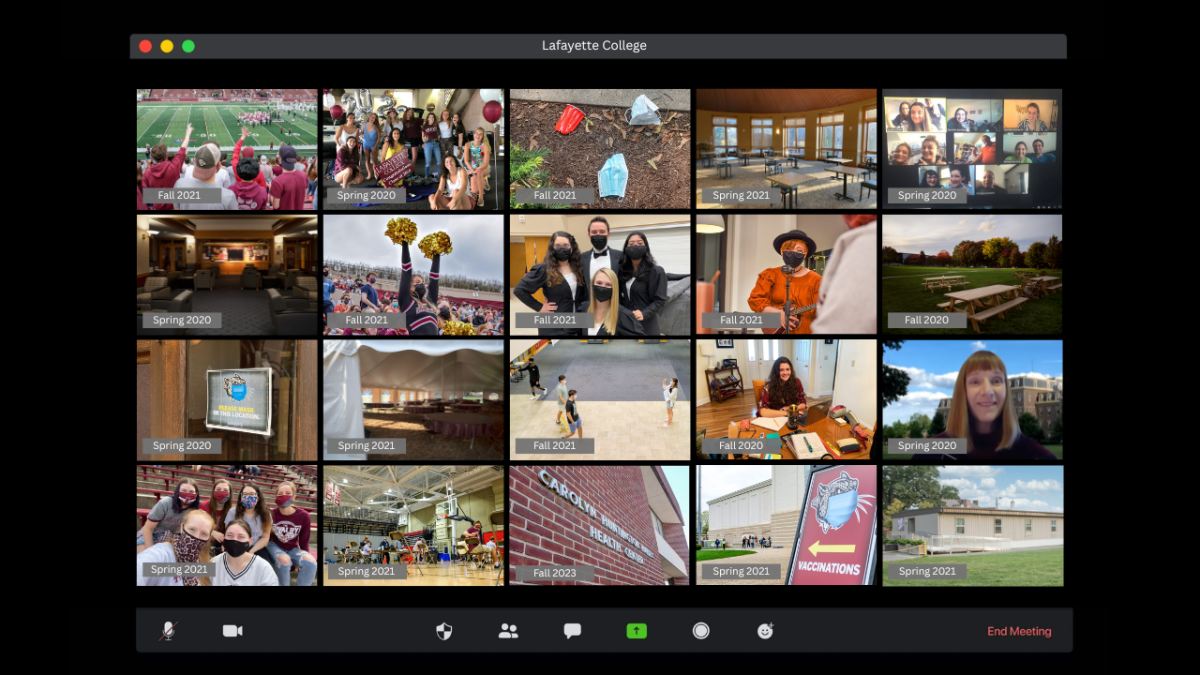

On Wednesday night, over 200 Lafayette students and professors gathered over Zoom to attend a virtual workshop led by Africana studies professor Wendy Wilson-Fall and George Washington University philosophy professor Vanessa Wills.

The workshop was part of the Olmsted Series on Race and Racial Justice, which seeks to “promote understanding of long-pressing ethical issues that the international civil rights movement, Black Lives Matter, has rightfully foregrounded in our public conversation,” according to the college’s website.

Professor Wilson-Fall began by stressing the importance of conversations about racism.

“The problem is that these issues will not go away. To face them requires real work. Like a disease, if these challenges are not faced, they’ll keep coming back. Not just over weeks, over months, but over years, decades and centuries,” Wilson-Fall said.

Wilson-Fall discussed a number of topics such as the notion that blackness is a government-constructed trope and the concept that when society deconstructs the current idea of blackness, a new identity that does not depend on whiteness must be built in its place. She critiqued All Lives Matter as a response to Black Lives Matter, explaining that the two are unrelated and that “the opposite of Black Lives Matter is Black Lives don’t matter.”

She concluded her remarks by asking the audience a key question about the United States.

“Is it a white country that happens to have a few minority populations or is it a multi-ethnic country that is evolving towards a new America?”

Wills described the racist origin of the term “white” which dates back to Colonialist America when it was was used to distinguish people of European descent from people of color. It was intrinsically tied to slavery, racism and oppression of Black Americans, she said. Wills went on to examine the idea that whiteness is not something one has or is, but rather something one does and performs.

Wills provided examples of what happens to white people when they stop performing whiteness. The first was a film in which a white man held up a Black Lives Matter sign outside of the Ku Klux Klan headquarters and was met with hate as well as disappointment and confusion, as spectators believed he was mentally unstable.

“The implication is again that these are sick outsiders who, if they understood the way that things should be, they would not be in solidarity with Black people,” Wills explained.

“How costly will it be for whites to stop performing whiteness?” she asked participants. She then unpacked the cases of white people who were lynched, disenfranchised, chastised and not given the same opportunities simply because they spoke out against racism and stopped performing whiteness.

At the end of the workshop, one participant asked, “As an academic setting, we’re taught that race is a social construct, that it was generally used to put people in a hierarchy, but how does that theory compare with individuals who say that Blacks aren’t dying because of the color of their skin?”

Wilson-Fall explained that this was a large oversimplification. Wills elaborated, noting that economic factors alone are not sufficient to explain the disparities in infection rates for Black Americans because they fail to explain the underlying economic disparity. According to the Mayo Clinic, COVID-19 hospitalization rates among non-Hispanic Black people are around 4.7 times the rate of non-Hispanic white people, likely due to differences in living conditions, access to healthcare, and discrimination.

“Can I eliminate race from the picture and still have some sort of economic explanation that will do the work of predicting who is more likely to die of COVID-19?” Wills asked. “That might be the case, that might actually be true, but that wouldn’t solve the causal question because then we have to ask ‘Well, why do the economics look like this?’”

Another participant expressed concern that whiteness is reinforced at every turn and asked the professors their thoughts about the best ways to represent anti-racist values.

Wills encouraged students to engage in activism, find grassroots movements led by people of color, ask them what would be helpful and listen to what they have to say.

Wilson-Fall advocated for students to be aware of their place in history and to “be brave enough to start that conversation with other young people via a book club or discussion group that meets once a month, just to support each other.”