Although it has been more than five years since Lafayette College agreed to reduce its carbon emissions, the progress it has made is hazy.

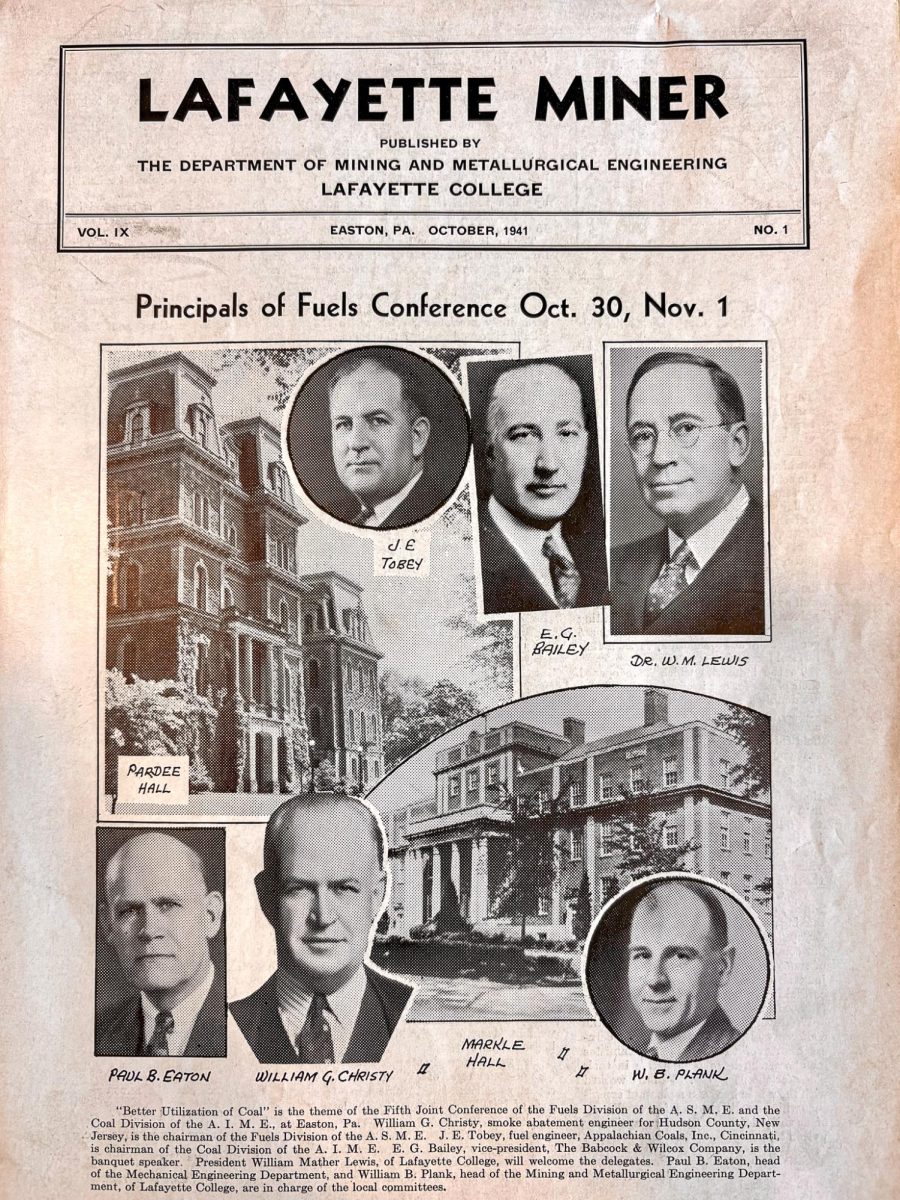

The Climate Action Plan, published in November 2011, outlines specific goals for the college to meet to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. Among them are updating the plan every two years, annually investing $400,000 into energy conservation measures from 2010 to 2020 and reducing the college’s greenhouse gas emissions by 20 percent by 2021 based on what they were in 2007.

Included in the plan’s requirements was keeping track of the college’s carbon footprint and the investments to reduce it.

But data concerning the college’s greenhouse gas emissions has not been kept in a centralized location since at least 2013.

Before the creation of the office of sustainability, Vice President for Finance and Administration Roger Demareski said goals outlined in the plan usually were tacked on to other positions, as well as the responsibility of the roughly 30-member sustainability committee. The committee of faculty members, students and administrators lists on its webpage that one of its goals is to be consistent with the goals of the college’s climate commitment.

“I just think anything managed by committee – you have to recognize that it’s accountability by committee, and it’s also a part of someone’s responsibility, not like [in Fechik-Kirk’s case], it is a full time job,” said Demareski, adding that more progress will be made on the plan now that there is an office dedicated to sustainability.

Until the data is collected from individuals and projects across campus, the college cannot know for sure whether many of the 2011 goals are on track.

“Well, there’s lots of data,” Director of Sustainability Marie Fechik-Kirk said. “There’s all the energy data that’s collected by the campus, so we have all that information. And what needs to happen is someone needs to put that all into the carbon calculator that we’ve been using in the past, and so all of that information just needs to be tabulated.”

The plan was one of the next steps after former President Daniel Weiss signed the American College and University’s Presidents’ Climate Commitment (ACUPCC) in 2008. The ACUPCC, now called The Carbon Commitment, a pledge for university and college presidents that their institutions will work toward having a net carbon footprint of zero, is hosted by the environmental organization Second Nature.

Fechik-Kirk, who started her job in November, and campus energy manager Nick DeSalvo, who was hired in January as a part-time employee, are now tasked with organizing this data to access where the college is on the plan. They plan to submit an updated plan to Second Nature in 2018.

Despite the college’s goal to update the plan every two years, Demareski said the college is working with the 2011 version to make the changes. He said he did not know if there was a more recent version than the one published five years ago.

“Ultimately, a place like Lafayette should publish a sustainability plan every year,” he said. “And we’ll do that.”

Demareski also said that the college plans to release a one-year, five-year and 10-year plan for sustainability initiatives next semester.

Assistant Director and Sustainability Planning George Xiques is listed as the person who uploaded the emissions data to Second Nature’s website from 2007 to 2013. Fechik-Kirk said this data was gathered by an organization outside the college.

When asked for comment, he referred The Lafayette to Demareski. Xiques did not respond for further comment in time for deadline.

It is also unclear whether $400,000 has been going to energy conservation measures at the college annually since 2010 as planned, and how much energy those measures saved.

Demareski, who started his job in 2014, said that because of the green aspects of other projects, “maybe half of our capital budget in some respect is going toward greenhouse gas emissions,” which would be much more than $400,000. However, the college does not track the specific funds that go toward a project’s energy conservation or how much energy is saved in these instances.

Demareski noted additionally that the low price of energy, like natural gas and electricity, over the past few years made incentivizing sustainability initiatives difficult. An energy-saving project will have a longer financial payback time if energy prices are low.

“I think you might also see, here as well as other places, things that were getting pushed five years ago, are not getting pushed any more. It’s because it’s hard to make the payback,” Demareski said. “It’s hard to do the right thing when it doesn’t make any sense financially.”

“I think Lafayette has always been doing things ,” Demareski added, citing a projects like replacing windows to conserve heat.

Director of Facilities, Planning and Construction Mary Wilford-Hunt cited the renovation of Grossman House, now a LEED Gold Certified building, as an energy conservation measure.

Data on how much energy these projects conserve is what DeSalvo is now collecting, Demareski said. Before DeSalvo was hired, Demareski said that people on the sustainability committee were tracking this data, but there was no centralized source.

“I think it’s been tracked at a committee basis with lots of people doing a little piece of it, and Nick’s job is to say, ‘What do you know? What were you tracking? What were you tracking? What were you tracking?’ And to pull it all together into a plan,” he said.

Fechik-Kirk wrote in an email that the college plans to “spend about $500,000 on energy related projects” in fiscal year 2018.

With this, the question remains as to whether it is likely that the college will reach its goal to reduce greenhouse emissions by 2021.

“I think we’ll know better once Nick does his analysis,” Demareski said. “I would say every indication right now says we’ll meet it. But we can only say that once we produce the data that says here’s where we are today based on what I’ve learned and all the pieces I’ve collected from every little person.”

Fechik-Kirk said she hopes the college does reduce its emissions.

“I would hope that’s the case,” Fechik-Kirk said. “And if we are thinking about—we still have several years until we get to 2020, so hopefully if there are things we need to do then we’d have a little bit of time to work on those things.”

Ian Morse ’17 and Kathryn Kelly ’19 contributed reporting.