“Black students at Lafayette need more Black students to fill out our community,” wrote James R. Hairston ’71, the former social chairman of the Association of Black Collegians (ABC) and one of the first black students to attend Lafayette College. “We need more Black students so that the Black experience is not lost but shared while we are being educated for ourselves, for our people, and for humanity.”

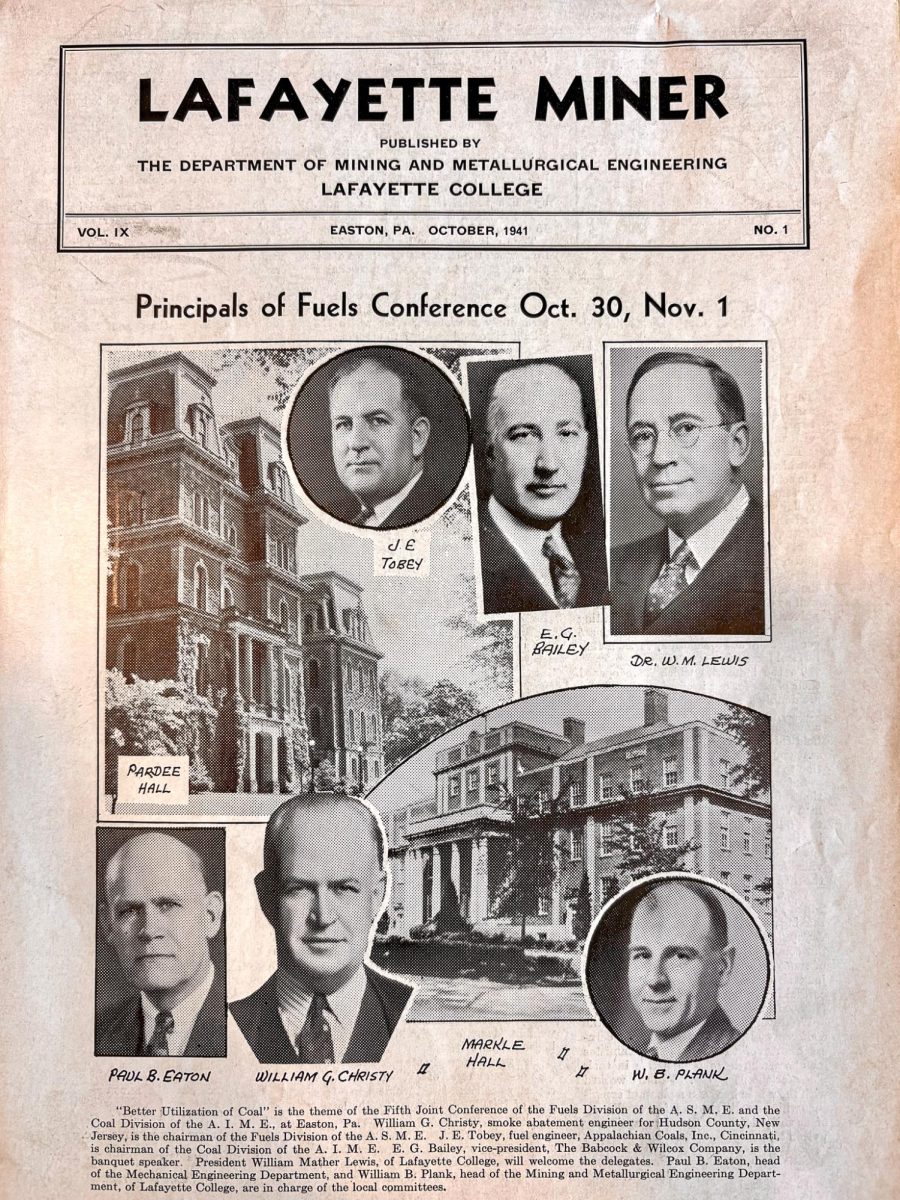

Students can visit the “Rapped in Black” exhibition on the first floor of Skillman Library to read more insights from Hairston and other black students who attended Lafayette in the 1970s. Created in a collaboration by ABC and the admissions office in 1970, Rapped in Black was a series of brochures developed for minority student recruitment. The brochures featured ABC members answering questions pertinent to the prospective black student. The exhibition credits Rapped in Black with increasing black student applications by three times the previous year.

“I think they were doing something really important by being honest,” said Grayce Walker ’22, ABC’s current historian.

Indeed, Rapped in Black is surprisingly truthful for an admissions pamphlet, almost irreverently so.

“Lafayette prepares the Black student as much as it can,” wrote Hairston in the first issue of Rapped in Black. “Short of changing the color of his skin.”

Also displayed in the exhibition is the Black Manifesto, a list of concerns organized by ABC upon its formation in January of 1969. The five demands outlined in the Black Manifesto were: 1) more black students, 2) the formation of black studies programs, 3) more black faculty and administrators, 4) the formation of a Black House, and 5) the end or neutralization of the effects of racism on campus. Over the next few years, Lafayette responded to the Black Manifesto by creating Rapped in Black, establishing the Black Cultural Center on the quad, and forming the Africana Studies department.

Despite this progress, many current students believe Lafayette is not doing enough to address the demands.

“We have so many black faculty and administrators, but we have so many compared to having none,” Walker commented, referring specifically to the third demand. “Anything seems like a lot when you start off with nothing.”

The Black Manifesto’s lasting influence can be seen in the recent list of student concerns addressed to President Alison Byerly after the 2016 presidential election. The 2016 student demands called for initiatives such as greater diversity training and implementation of gender-neutral bathrooms, but it also echoed the Black Manifesto by demanding increases in faculty of color and courses in departments like Africana Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies (now Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies).

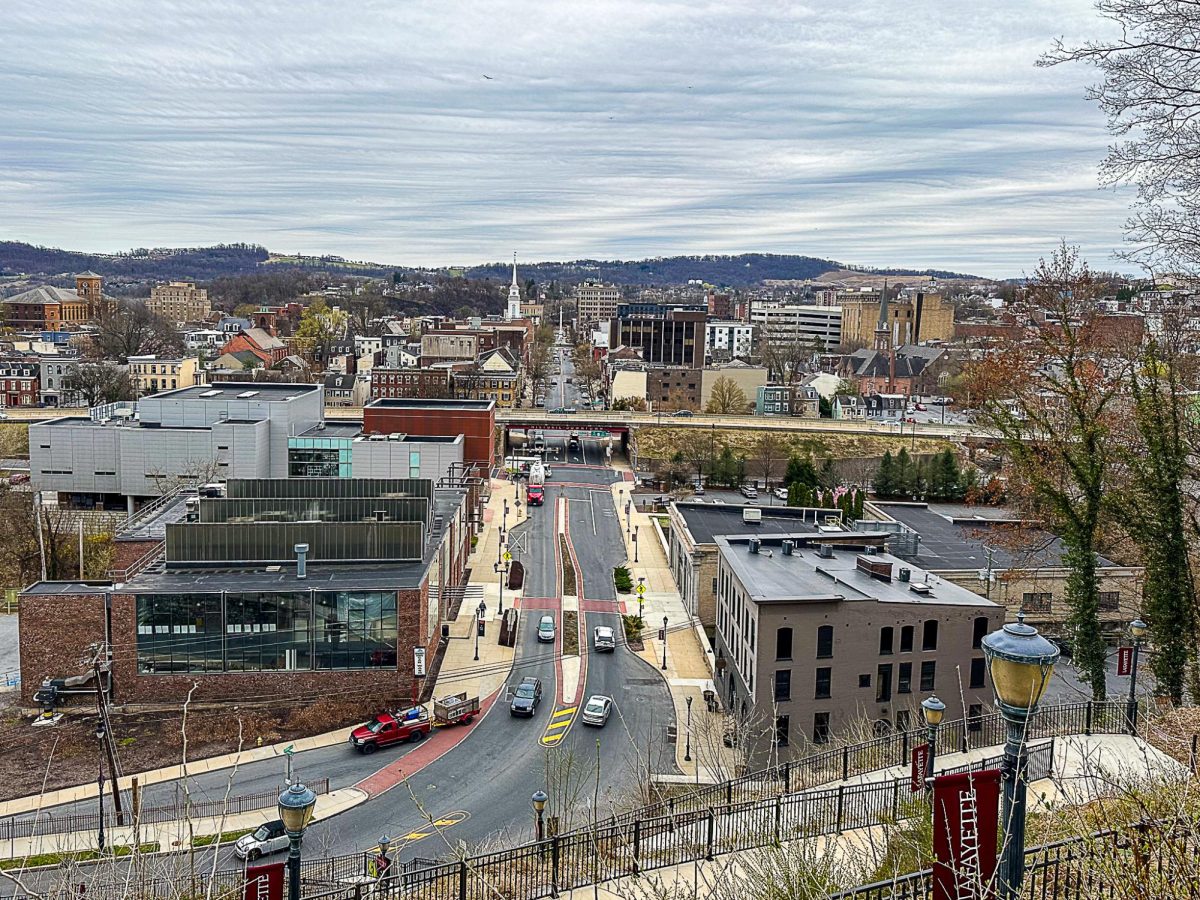

According to Rapped in Black, there were 43 black students among Lafayette’s 1,850 male students in 1969, which amounts to about two percent of the student population. Today, seventeen percent of Lafayette’s US students identify as people of color, and ten percent of students are international. Five percent of students identify as African-American according to the Lafayette website. Although the minority student population has certainly increased in the fifty years since ABC’s formation, Walker said this is not enough.

“When you look at a hundred, two hundred odd [non-white] students compared to a body of two thousand…the numbers we have here are not necessarily impressive,” Walker said. “I know as a black student they don’t feel impressive.”

Although she is underwhelmed by the college’s efforts to increase the student of color population, Walker acknowledges how difficult multicultural recruitment can be. Cristina Usino, the Associate Director of Admissions for Multicultural Recruitment and Student Access, is a strong advocate for the efforts the Admissions Office is taking to increase the student of color population.

“Our team of access meets in each application round to review students from historically underrepresented backgrounds and identities (racially, ethnically, socioeconomically, religiously, sexual orientation and gender identity) to provide a team expert review and provide an advocacy rating before the student’s application gets reviewed in our general committee,” Usino explained in an email. “My role in particular travels to public, charter and historically exploited and or underserved communities and their high schools for recruitment of students of color.”

Both Usino and Walker agree that increasing the non-white student population continues to be a pressing issue at Lafayette.

“Multicultural recruitment is not only imperative for the success of the entire Lafayette community,” Usino said, “but it’s revolutionary in that it emboldens our divisions and community to create new systems, practices and rewrite social scripts.”

“When you’re a person of color, when you’re first [generation], when you’re a queer person, you come with such a huge, intense responsibility to save the world in four years by getting your degree,” Walker said. “I want everyone to have the opportunity to just be [without] the added weight of responsibility that the world has unfairly given them.”

Although Lafayette does not produce Rapped in Black anymore, Walker said she recently met with Usino to talk about reviving Rapped in Black for future semesters.

“I was elated to learn of a historical partnership between ABC and admissions for recruitment and felt like it was time to reignite the flame they had lit in the 70’s,” Usino said. “I would like to keep the wraps on any more detail as to what is to come (pun intended), but I can say that I can’t wait to use our history to shine our present and invigorate our future.”

For now, Walker hopes that the college will pursue more initiatives to increase its non-white student population.

“Lafayette is so special hugely in part to the people who are not white. We bring so much to this school… and that is true of this country,” Walker said. “Non-white people made this country what it is. I think Lafayette does itself a huge disservice when it refuses to acknowledge that.”