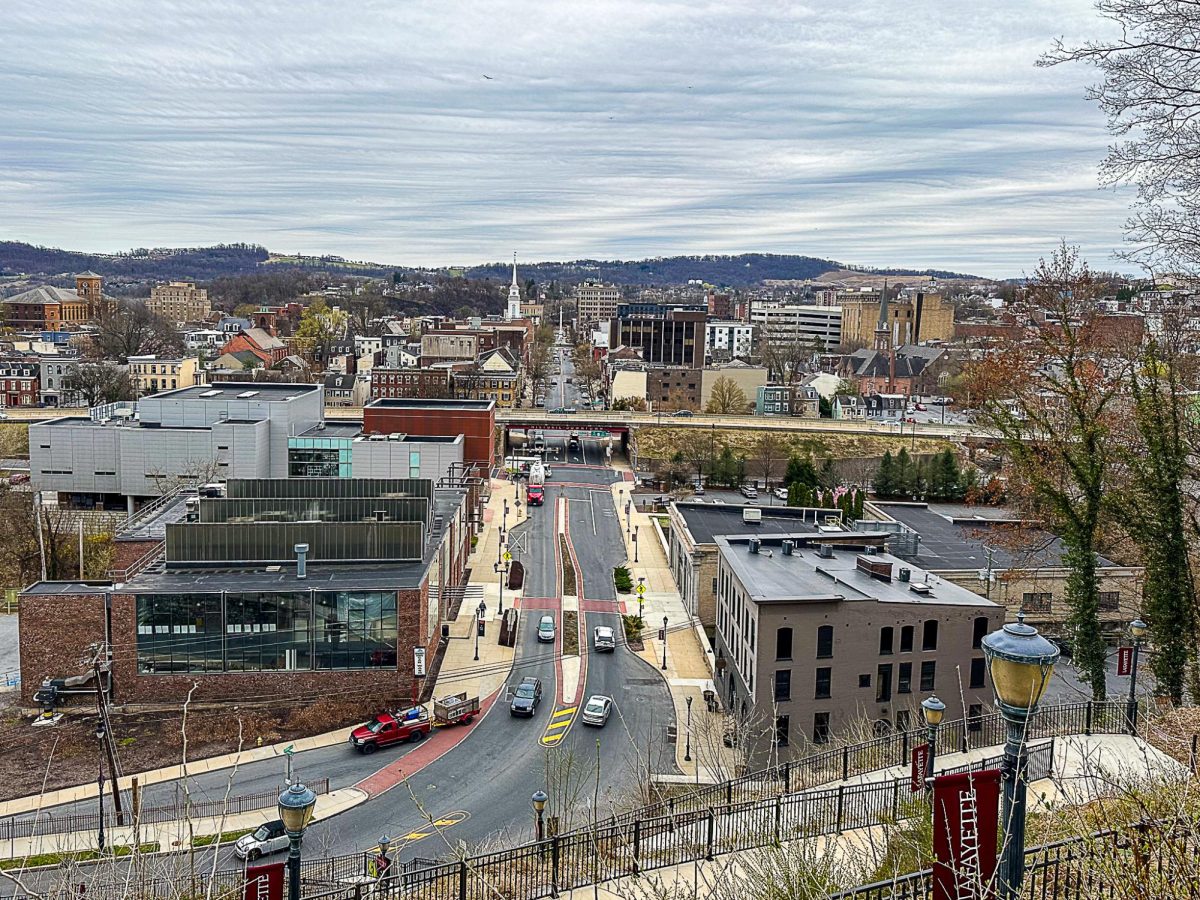

The Easton city council approved phase two of the college’s expansion plan last Wednesday after initial hesitations from members of the planning commission earlier in the year. The project will involve the demolition of several houses on College Hill to make way for a 169-bed residence hall with a new health and wellness center.

Phase two follows the opening of the McCartney residence hall this fall and is part of the college’s ongoing effort to grow the student body population by 400 students by 2025. It will also involve the relocation of the Portlock Black Cultural Center from its current home at the intersection of McCartney Street and Clinton Terrace.

The planning commission granted preliminary approval in early August for the project with the request that the college present a definitive timeline for the construction. At the time, the Morning Call reported that some members of the commission were concerned that the school would demolish a block of buildings without constructing anything in its place.

President Alison Byerly said this concern was “unnecessary.”

“This project sits at our front door,” she said. “We would not be prepared to move forward at all unless we felt confident we could finish it.”

“There would be no benefit to us to having a huge hole on the campus if we failed to finish our project right now,” she added.

Moreover, Vice President of Finance and Administration Roger Demareski noted that it is not part of the standard procedure for building permits to require a timeline for approval.

“They’re really not allowed, under their own ordinances or their own laws, to require a definitive timeline,” he said.

He added that building permits like the one granted to the college on Wednesday are good for five years and that he hopes to have phase two completed by 2023, even with the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic.

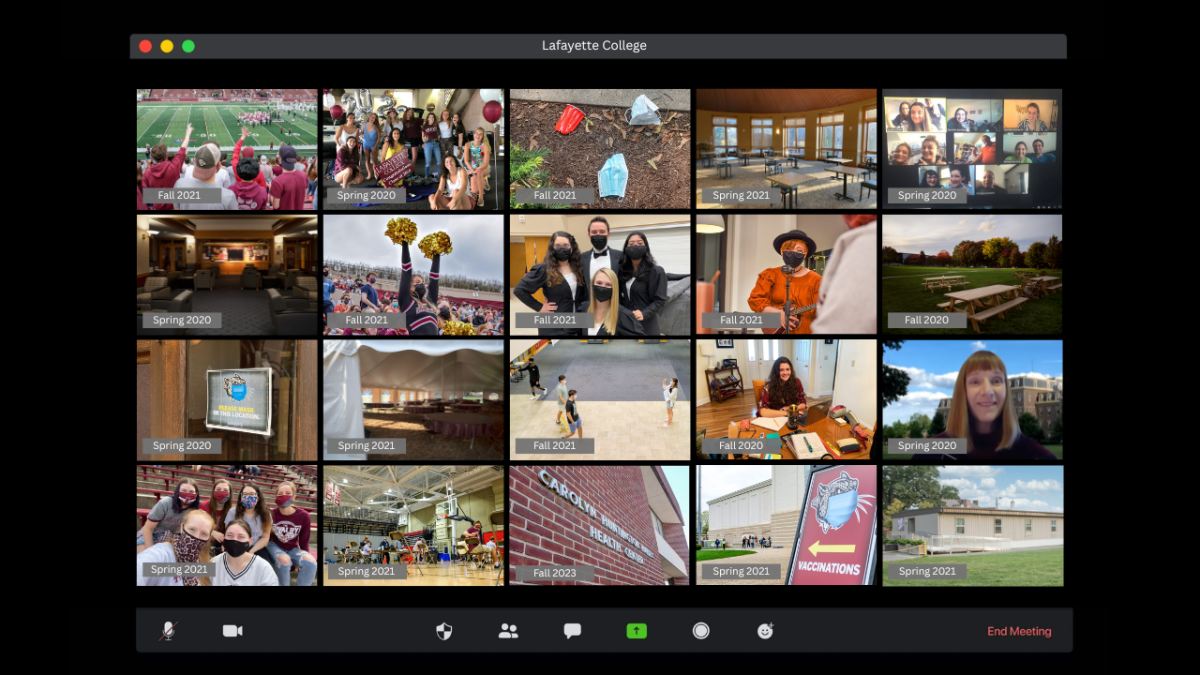

This projection, however, hinges largely on the enrollment numbers in the next several semesters. The college would not embark on phase two of the project unless they “thought it was necessary,” according to Byerly, which would require not only a return to last year’s enrollment numbers but consistent growth in the student body population in the coming semesters as part of the ongoing strategic direction.

Part of the goal of the strategic direction is to increase the financial aid budget and transition to need-blindness in the admissions process by 2027. By growing the student body population, the additional revenue would increase the available funds for need-based financial aid.

Now, Byerly said this goal has been set back a few years.

“I’d be pretty surprised if we were able to grow enrollment next year,” she said.

She added that growing the student body population was always a “means to an end.” The school has other ways of increasing revenue, including the annual tuition increases and fundraising.

Achieving their financial aid goals could involve “looking more carefully at overall costs, for example, rather than simply adding revenue to additional students,” she said.

“We remain committed to making Lafayette as accessible as possible as a primary goal,” she said. “Figuring out how we achieve that financially might have to be tweaked in the coming couple of years as we see how things play out.”

One of the buildings that will be removed to make way for the phase two construction is the Portlock Black Cultural Center, which was founded in 1970 after students demanded a “Black House” in a document entitled the “Black Manifesto” in 1969. Originally called the Malcolm X Liberation Center, it was located in a building near Hogg Hall until it was demolished and moved to its present location to make way for the Farinon College Center. It is a home for many student organizations, art exhibitions, guest lectures and speakers and community programs.

The center is planned to be renovated and moved to a new location adjacent to the Hillel House. It will occupy the space currently held by the houses at 41 through 45 McCartney Street, which will all be demolished as part of the construction process.

“[This space] is really a primary gateway to the college, and we really wanted to have something special there and something really meaningful,” Vice President of Campus Life Annette Diorio said.

Changes to the building will include an addition of several thousand square feet, a large wrap-around deck for outdoor social events and a fully renovated interior.

Planning for the renovation initially started in 2017, when Diorio said that the school hosted several open meetings with students and alumni to solicit feedback about what the new building should look like. Since then, she said that student involvement has been more “low-key” as the college was not in a position to start construction.

She added that the college had a closed meeting with a group of students two weeks ago. The students gave feedback involving the interior design of the building, but also requested that the school go through minority-owned businesses whenever possible during the renovation and moving process.

The college has also been working to address growing concerns online over the move. An Instagram account with the handle @dearlafayettecollege has garnered more than 1,600 followers in the last several months and has several posts detailing student concerns over the second relocation of the Black Cultural Center at Lafayette, likening it to forced displacement and gentrification.

Byerly said that the school hopes to address these concerns by integrating the memory and history of the old house into the new one and to involve students in the process whenever possible.

“I understand that for a group that already struggles with the feeling of marginalization, feeling displaced is particularly uncomfortable,” she said.

The new house is planned to include exhibits and memorabilia from the old Portlock Center, as well as a history of the building and the movement built into the program and decor of the new building.

“Honoring the old space will absolutely be part of the new space,” she said.