In the electrical and computer engineering department, Padmanabh Kaushik ’25 and a team of researchers are working to help develop a world where disorders like dyslexia can be diagnosed through an online computer game.

In many countries, it can be difficult to get a dyslexia diagnosis early on, whether due to stigma surrounding the disorder or the overall lack of knowledge on the subject. This may lead to complications as the child progresses through school and other facets of their life. With an early diagnosis, children are able to access specialized learning programs and treatments that would help them navigate challenges they might face early on.

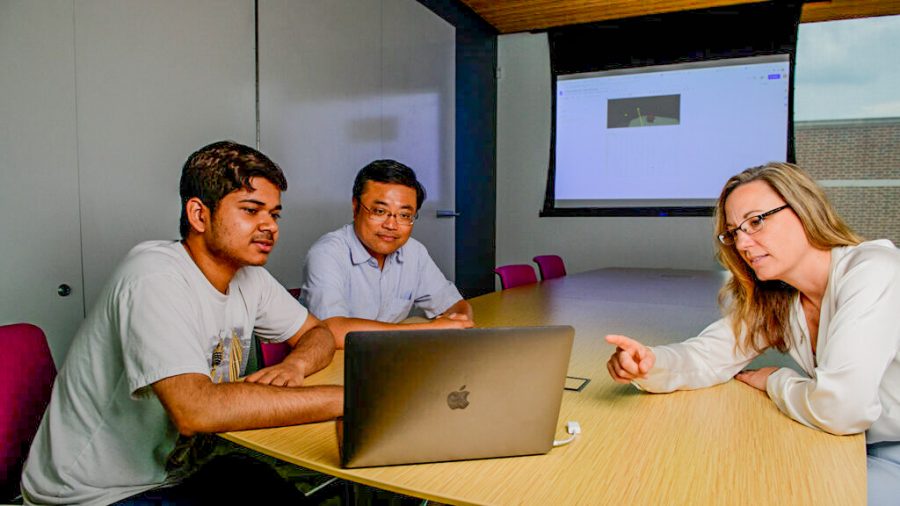

Last year, Kaushik approached electrical and computer engineering professor and department head Yih-Choung Yu with a request: he wanted to work with real human data. The electrical and computer engineering department had already been looking into the use of eye-tracking technology and how it could work as a diagnostic tool, and Kaushik was able to join the research team over the summer.

In their study, elementary school-aged participants sit down, open a webpage and navigate through a digital maze using a small plastic joystick. Ideally, their eye-gazing behavior will eventually be used to produce an easy and efficient disorder diagnosis. While Kaushik mainly focused on the various data sets from all over the world, he found that the challenges that came with real human data kept him interested in the complicated results.

“My favorite part about doing the research was dealing with real human data and working on ways to quantify human decision-making processes,” Kaushik wrote in an email.

According to Kaushik, it is not easy to quantify something as complex and nuanced as human behavior. Like any technology, tools like this one have their limits.

“Some instruments, like the joystick, were just meant for playing video games, so they did not have an interface that could transmit and record data to the accuracy of a fraction of a second with the software recording it,” Kaushik wrote.

Working with imperfect technology can cause some differences in data. “These were instrumental errors, not human errors,” Kaushik wrote.

Along with doing his own work with the engineering department, Yu paired with neuroscience professor Lisa Gabel to further look at the connection between eye movement and the possible diagnosis of dyslexia. Kaushik noted that there were a variety of variables to the research, including the possibility that some children just weren’t as good at video games.

“It’s an online game, and some people are just bad with technology … honestly, I’m one of those people,” Kaushik wrote.

Working with the neuroscience department provides a different viewpoint that is helpful for improving the experiment. In his time doing research, Kaushik found that accessibility was one of the most important factors to him. Being able to consistently improve the system for real people was another added bonus that came with analyzing real human data.

While there’s a long way to go before eye-tracking data can be used to diagnose specific conditions, looking at Kaushik’s research, the future doesn’t seem so far away.