Chemical reactions in atmospheric particles can significantly affect the quality of human life and serve as a warning for global warming, chemistry professor Melissa Galloway told students and faculty on Tuesday.

“I’m an atmospheric chemist,” Galloway said. “I think in terms of air quality. I think in terms of the atmosphere.”

As this year’s speaker delivering the Thomas Roy and Lura Forrest Jones Faculty Lecture, Galloway, who was awarded an NSF grant for her research last year, presented her recent research at the Tuesday evening event in Oeschle Hall.

Created in 1973, the Jones Faculty Lecture provides the Lafayette community with the chance to hear informative presentations from exemplary individuals.

In her tenth year at Lafayette, Galloway wanted to talk about how her research topics affect the Earth’s air quality. Her lecture paid attention to the global warming crisis and various kinds of air pollution. The air particles that Galloway primarily studies are not visible to the naked eye, but are influential when it comes to changes in global weather and temperature patterns. These could result in dire consequences in the future.

“The very small particles … they’re going to get into your bloodstream, and they can cause heart disease, brain issues … neurological issues,” Galloway said.

Galloway’s main focus, however, is not on human health, but on the environment.

“I think about particulate matter in terms of what it does to our skies,” she said.

Galloway used her research to reference the pollution issues sweeping many American cities, featuring numerous photos of urban pollution in her presentation.

“You’ve probably all seen pictures of [Los Angeles] smog at some point,” Galloway said. “This smog is made up of ozone in the gas phase, nitrogen dioxide in the gas phase and particulate matter. This happens more in L.A. because it’s hot there.”

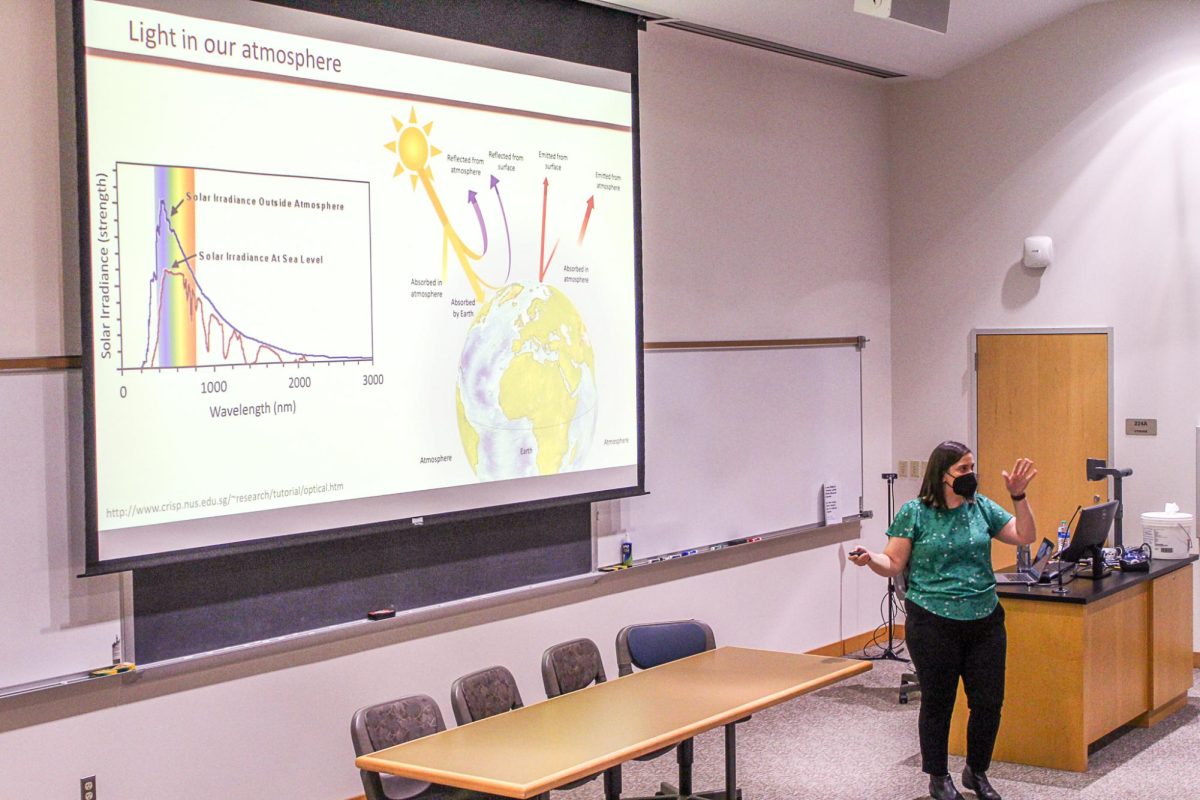

Galloway’s lecture also emphasized light entering Earth’s atmosphere.

“When we get light coming into our atmosphere, three things can happen to it,” she said. “It can be absorbed by something in the atmosphere … it can be reflected from the atmosphere … or it can come all the way down to Earth and be absorbed by Earth or reflected off of the surface.”

When discussing the various pollutants humans produce, Galloway made note of black smoke’s tendency to absorb light and white smoke’s tendency to reflect light. These different reactions affect the Earth’s climate in different ways.

“What I think about is the difference between this absorption, and this reflection, because that changes how much light we get at the surface of the Earth,” Galloway said. “That changes things like global warming [and] global cooling. Absorption leads to a little bit of warming, reflection leads to a little bit of cooling.”

While presenting her research, she also emphasized the importance of having open conversations with those unfamiliar with chemistry.

“I just gave a talk to a room that wasn’t full of chemists about something that I think is important,” Galloway said. “Being able to have a conversation with people outside my field about what I do, and to teach you something, I think is so important.”

Galloway emphasized the importance of educating people through her research.

“We need to be able to understand what’s happening in the humanities, and the humanities need to understand what’s happening with us,” Galloway said. “When we’re talking about misinformation about [COVID-19], and climate change … we need to be educated to be able to have a coherent conversation.”

Chip Nataro, head of the chemistry department, echoed Galloway’s sentiment.

“This is a science that impacts everyone,” Nataro said. “We all need air and air quality is really important as is discussing what impact this can have on global climate. I think she did a magnificent job of making the material approachable for a general audience.”

“[Galloway] is an amazing colleague. I’m privileged to work with her,” Nataro continued. “She’s an amazing scientist, an amazing teacher … she is a tremendous resource and support for our students.”