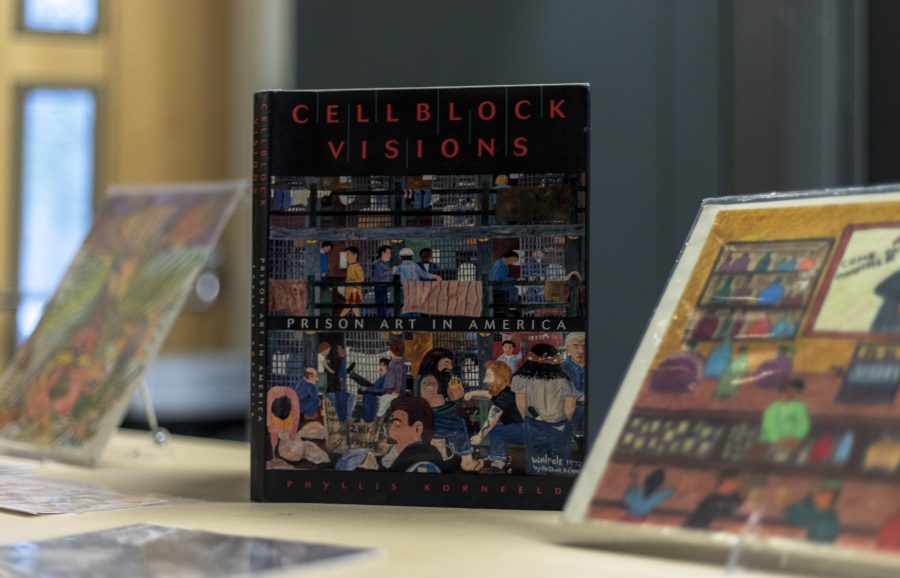

Phyllis Kornfeld began teaching art to prison inmates 35 years ago, when she began work at the Oklahoma State Prison. Whenever Kornfeld meets a new inmate, she said she always tells them: “We are going to access that part of you that has never been incarcerated, never been abused, and never been an abuser.”

Kornfeld, a prison art specialist, has been teaching for nearly four decades, but she said that there is “not a hint of burn out, this job is very heartbreaking and very exhilarating.”

“[My goal is to] find opportunities to give these folks to engage in something creatively,” she said.

Kornfeld’s talk was part of the Criminal Justice Reform Awareness week hosted by the Landis Center, a program on campus that specializes in building campus community, services learning and student growth.

Mayna Chen ’18, team leader of student coordinators, said that Kornfeld was invited to talk because she offers an inter-disciplinary approach to criminal justice. Chen said that Kornfeld would bring up conversations that are normally not talked about.

“Most of the folks have a strong sense of unworthiness–that’s how they’ve been treated their whole life … [It is a] heavy trauma, to go to prison. Not to mention what they’ve experienced before they went to prison,” Kornfeld said.

She said that it is beautiful and exhilarating to see “a person suddenly discovering a part of themselves they never knew existed. It changes everything.”

A warden who works at the same prison as Kornfeld noticed the impact that art had on the inmates, according to Kornfeld.

“’When a man makes art, I see him in the yard, he stands up straighter, he seems cleaner, he says good morning to people,’ [the warden told me]. This was the significance,” Kornfeld said.

Prison art in its essence, according to Kornfeld, is for “people who have been routinely dehumanized to find themselves, to reinforce the fact that they are indeed human beings.”

Due to the lack of other art materials, everyday objects are constantly being creatively turned into paint, paint brushes, paper, and even frames for their own artworks. Potato chip bags, cigarette boxes, ramen noodle wrappers and toothpicks are some of the most common materials that inmates love to collect over the years, according to Kornfield.

There are many different types of prison art: the more traditional and popular art form is “Enveloped Art,” where inmates draw on the envelopes themselves and send it off to their families; “Handkerchief Art,” is also a popular art form amongst inmates because of easy accessibility. Those inmates often send home their handkerchief arts which would later be framed by their families, according to Kornfield.

For some of the inmates, Kornfeld said, they finally discover their passion for drawing during their incarceration.

“In the movies, it’s the toughest men that are heroes. In prison, the best artists are right up there…[and] getting admired,” Kornfeld said, adding that most of the inmates have not done art since they were little kids, and when they finally start doodling and drawing, “beautiful, uplifting works are being created.”

Kornfeld is thankful that she has had the experience to work with prisoners, and she does not plan to stop anytime soon. Her art education has left the limitless influence on the inmates, and she believes that “art truly transcends people.”

Kornfield shared some of the things that her student-inmates have told her as they were released:

“I am a wiser person now.”

“This goodness was always in me. I will come out of here with compassion.”

One of Kornfeld’s students, who has been taking art lessons with her for eight years, was finally getting released. Prior to his departure. Kornfeld asked the inmate,“What do you think is going to be changed in your life since you’ve been doing art in prison?”

“I learned to exercise my gift. I will have a purpose,” he replied.