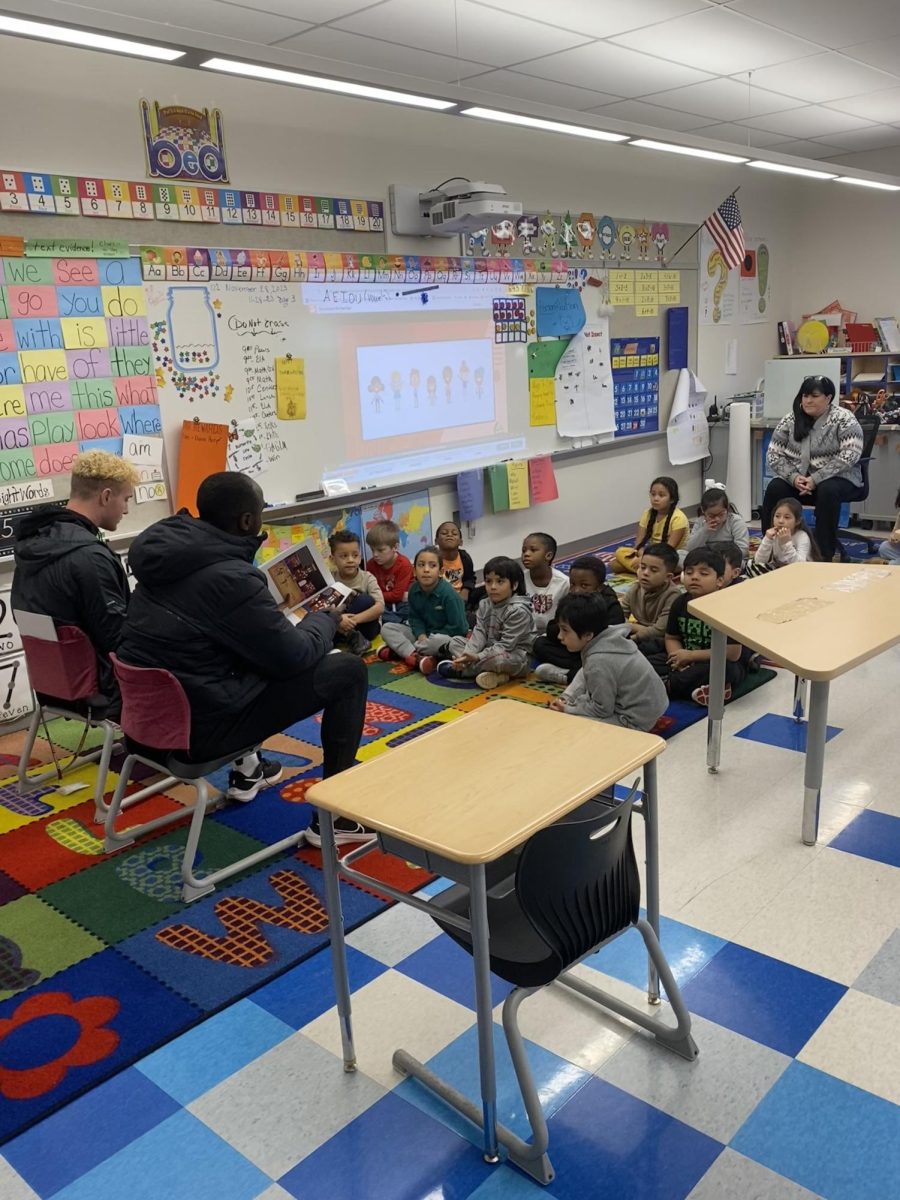

Professors Jenn Rossmann and Mary Armstrong discuss positive effects of WGSS courses on STEM students

This word cloud from Professors Armstrong and Rossmann’s research, which heavily features the word ‘critical,’ demonstrates the main takeaways that STEM students learn from WGSS courses. (Courtesy of Rossmann & Armstrong, ASEE 2021)

February 18, 2022

Making science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) more inclusive requires more than just increasing the proportion of women, people of color and other marginalized groups in the field. In their award-winning research, Mechanical Engineering Professor Jenn Rossmann and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies (WGSS) Professor Mary Armstrong explored how WGSS courses can foster confidence and a sense of belonging among marginalized STEM students.

The pair discussed their research in a talk this past Wednesday.

Rossmann initially noticed in exit surveys for mechanical engineering majors that when students were asked about the most valuable non-engineering class they had taken at Lafayette, many answered with WGSS classes. In fact, Rossmann said that 70% of the mechanical engineering students who took a WGSS class found it to be the most valuable of the 20 or so non-engineering classes they took. This observation kickstarted Rossmann and Armstrong’s research.

Their research involved administering an informal exit survey at the very end of Armstrong’s Gender and STEM course, an interdisciplinary WGSS course investigating how STEM fields both shape and are shaped by ideas about gender, race, ethnicity and sexual identity. Rossmann and Armstrong also interviewed a small group of students who completed the survey for more in-depth conversations.

From the exit survey, Rossmann and Armstrong learned that students who took Gender and STEM experienced three changes: 1) a shift in understanding of STEM experiences from the individual to the systemic level; 2) increased agency and confidence and 3) an ability to critique the assumed objectivity of STEM. The in-depth interviews only reinforced these findings.

They also found that students experienced a new relationship to their STEM identity that involved a greater sense of belonging within their field.

“This [WGSS] class has made me feel more at home in the STEM field than any of the 15+ STEM classes I’ve taken,” one student from the study said.

Overall, Rossmann and Armstrong’s research shows that diverse STEM students felt empowered and liberated by WGSS courses like Gender and STEM. Students also felt strongly that others would benefit from such coursework.

However, more work still needs to be done. Rossmann and Armstrong argued that offering a course like Gender and STEM cannot be the end of Lafayette’s efforts to make STEM more inclusive.

For instance, because of the low number of professors who regularly teach for the WGSS department, Armstrong is only able to teach Gender and STEM once a semester. According to Armstrong, a single 15-week course cannot capture the full complexity of intersections between STEM, gender, race, ethnicity and sexual orientation. Rossmann and Armstrong argued that there needs to be more WGSS courses about STEM studies in order to reinforce these crucial concepts.

Finally, Rossmann and Armstrong emphasized the responsibility that STEM itself has for making the field more inclusive.

“Even if we had a hundred faculty in WGSS, it still would not release STEM departments and programs from their responsibilities in terms of creating content and a climate that is welcoming to students. So STEM still has a job to do,” Armstrong said. “Even if everybody in the world could take — or even had to take — a WGSS class…there’s still a lot to do.”