With the changing of seasons also comes the changing of plants. Between annual flowering plants and hanging baskets, a splash of color is brought to campus in the spring, summer and fall to attract visitors and prospective students.

“Jeff Weed is our grounds supervisor, and he actually has a landscape architecture degree,” director of Facilities Operations Scott Kennedy said. “He selects the flowering plants that we change seasonally and gets [them] from local sources.”

Lafayette developed a landscaping policy “in coordination” with the Office of Sustainability, Samantha Smith, the sustainability outreach and engagement manager, said. The policy itself was created many years ago, according to Kennedy, who said that his division aims to use native species.

The college employs third-party contractors and “give[s] the contractors [Lafayette’s] policy and asks them to use native plants,” Kennedy said.

However, that is not always possible.

“It could be the site condition, whether it’s a real wet area or shady area or a steep slope. Sometimes we have to deviate from that but the contractor would have to get Jeff Weed’s approval. We try not to [deviate] if we can,” Kennedy said. The availability of native species, especially from “local growers,” can also affect the selection on campus.

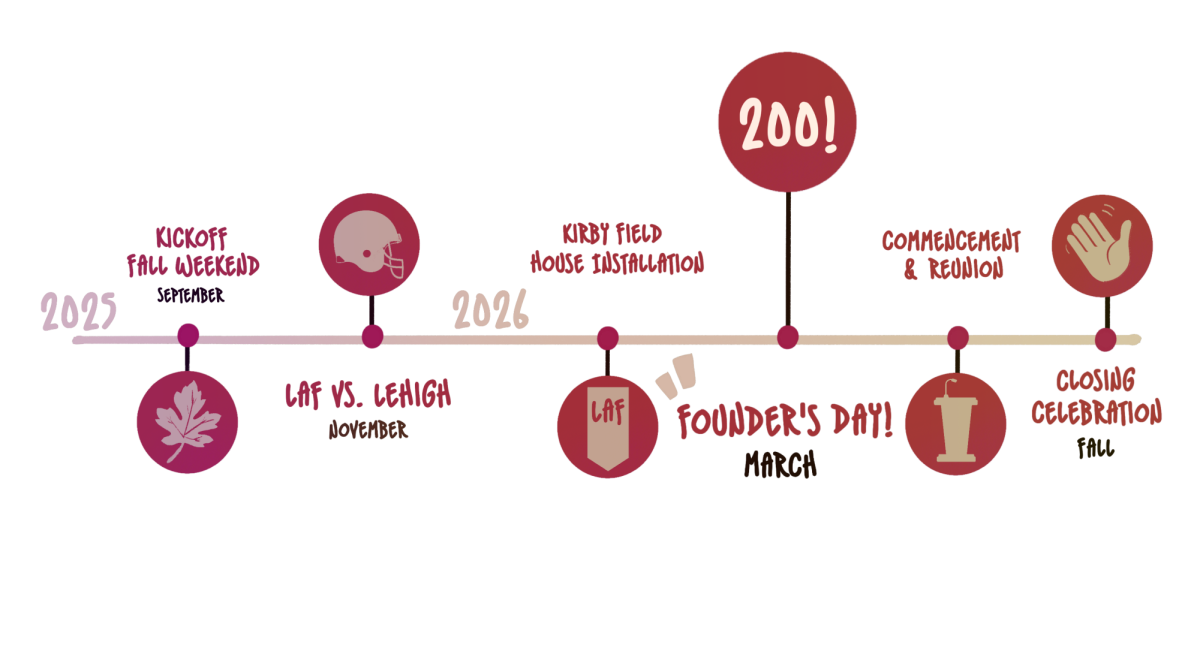

Chrysanthemums are “out right now for the fall season,” and the “maroon, yellow mums [were] done a couple of weeks ago,” Kennedy said. During the winter, “we don’t do much landscaping,” he added.

There is also a distinction between the levels of maintenance required for various plants.

“Annuals you plant each year, and the perennials come back every year on their own. All the flowering plants we use are annual plants,” Kennedy said.

Lafayette also has guidelines to enforce the policy, particularly with third parties.

“All of our construction is managed by a company called Aegis … and they have construction managers on-site,” Kennedy said. “They monitor the contractors adhering to that policy.”

Additionally, approval from Weed is necessary for non-native plants to stay.

“The policy can grow over time,” Kennedy said. “Any of the substitutions [are] approved. We make sure they’re not an invasive species.”

Non-native species, however, are not inherently invasive.

According to Nancy Waters, associate professor of biology, an invasive species is a “species in a given habitat that has detrimental impacts to the whole community and/or ecosystem it is located in. It’s very site-specific.”

“They may have deleterious effects in the short term, but those might subside over the long term if ecosystems are resilient enough to accommodate the dynamic change,” Waters said.

Waters said that the preferred overarching guiding principle should be to treat all plants with respect and care. Sometimes, species can “impose unintended problems and develop into new nuisance species, and, therefore, become invasive species.”

One development spearheaded by the Office of Sustainability is a database of trees on campus in the form of a readable map for “research purposes and engagement purposes,” Smith said. This project includes adding plaques with QR codes that contain information about the trees, such as whether they are native or non-native.

“There is something to be said for the kinds of beautification of campus that happens with the seasons,” Waters said. “That can provide a real, intrinsic value that it might not have if we restrict some of what we do. A productive balance is not a bad thing to seek here.”