Lafayette is not known for its diversity, but sparingly, students of color are dipped in the college’s history. This does not mean, however, that Lafayette is a model of inclusiveness and diversity, according to some students of color on campus.

While Lafayette’s record may be lacking students of color, black history is complex and engrained at Lafayette.

Aaron O. Hoff, who was a free black man, was part of the first class of students when Lafayette officially opened on May 9, 1832. Hoff was born in 1808 in Warren County, NJ and in 1831 enrolled at the Manual Labor Academy of Pennsylvania in Germantown, Pennsylvania. The student body and curriculum of the Academy was moved to Lafayette and included in the Lafayette Charter one year later, in 1832.

One of Hoff’s duties was to announce the hours of awakening and reciting for students. Diane Shaw, the Director of Special Collections & College Archives, wrote in an email that though Hoff had more responsibilities than other students, there is no reason to believe Hoff did not study at the college.

Eleven black students attended the college from 1832 to 1846 before a span of 100 years in which Lafayette did not accept applications from black students. In 1947, Lafayette allowed African-American students to apply to the college.

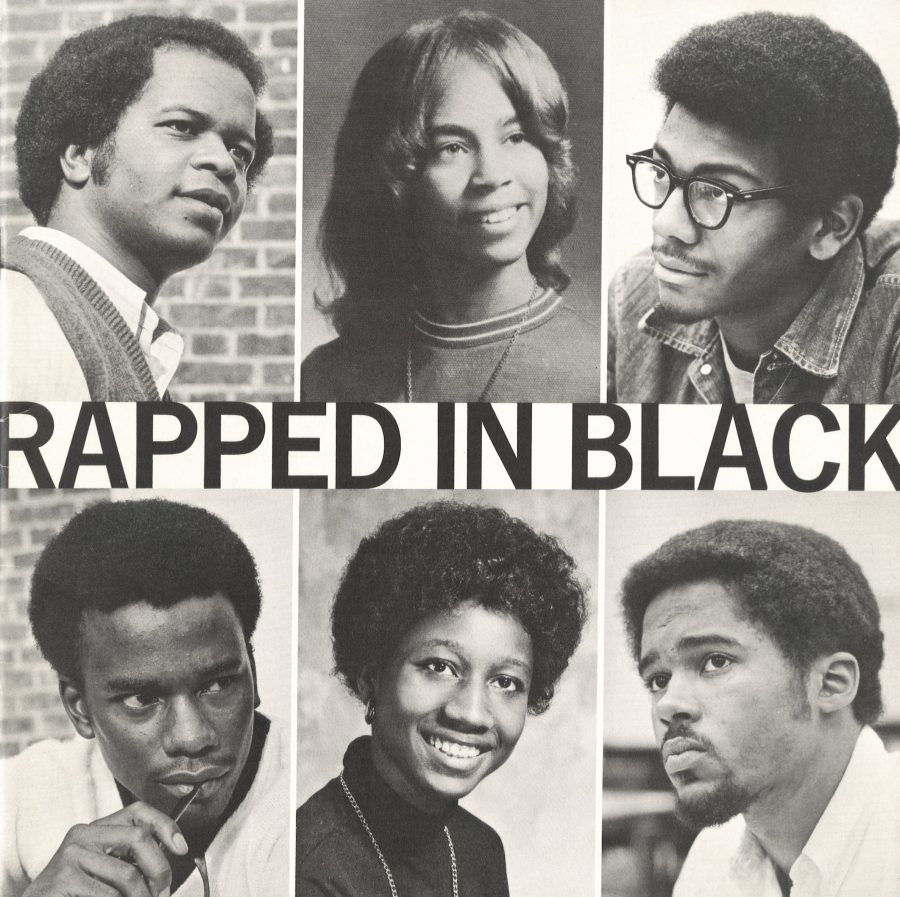

Black students at Lafayette created the Association of Black Collegians (ABC) in 1969, which was funded by student government. Along with the organization, students created Rapped In Black, a booklet for African American students to express their opinion on the college’s racial climate.

In the second edition of Rapped, which was published in 1970, Bill Fault ’73, expanded ABC’s goal to include the improvement of the academic and social environment for black students.

“We are actively involved in recruiting brothers and sisters and increasing Black Studies courses. We help brothers and sisters in academic difficulty, organize parties and other social gatherings, and publish newsletters and student directories for Black Students in the Lehigh Valley,” Fault wrote.

In 1970, the college began to accept women, including 14 black women, according to Rapped.

Though the second booklet of Rapped featured two black women on the cover, their voices did not appear until later issues.

In the booklet, black students submitted questions that members of ABC would answer. Questions persisted on the racial climate at Lafayette and how black students had been dealing with it. They also addressed the ways in which they wanted it to change.

“In what ways might I be disappointed in Lafayette?” was one of the questions three students answered in Rapped.

“A black student could be disappointed by the seemingly [all-white] way, by the shortage of social life, or just disheartened by the fierce academic competition,” Jon Cureton ’70 wrote. “Black students have an identity of their own that can be lost if these identities are not maintained by some common bond between blacks.”

“Through the ABC the black student can, by uniting, overcome many of the barriers of white college life,” he added.

In Rapped, the students listed their concerns. Amongst them were requests for more black students, black faculty members, black administrators, black studies courses, a black cultural center and the “end or neutralization of the effects of racism on this campus.”

According to Lafayette’s site, 17 percent of Lafayette’s U.S. students identify as students of color: six percent identify as Hispanic/Latino, four percent as Asian-American, five percent as African-American and two percent as multiracial.

Charles Evans ’19, the current president of ABC, said that black students are still trying to achieve the listed goals of Rapped today.

“[Students] on campus came together and had a list of concerns that, when you look at what was included in the Rapped In Black, [it] was almost identical … what they were asking for, versus what we [are] asking for, and really basic things, you know like actual support of students of color and in our case, black students.”

In December of 2016, a collaborative effort between groups on campus generated the list of concerns for marginalized students on Lafayette’s campus, which included a call for more black and African-American faculty among other matters of diversity. Once submitted to the administration, the list resulted in the creation of the Equity, Transformation and Accountability Board which is still active as of this academic year.

“The main goal of the ‘Rapped In Black’ list of demands and the list of concerns more recently is support from application to graduation, meaning that we have so many bright black students, brown students from all over, but they come here and they fall by the wayside and are forced to support one another,” Evans added.

To celebrate Black History Month, the college has planned a few events including a celebration of Playwright August Wilson by Riley Temple ’71, an African-American alum.

Dean of Equity & Inclusion Christopher Hunt wrote in an email that the college doesn’t know how many students will attend BHM events, but that he hopes to educate students about Black History.

“We don’t have a predetermined number of students that we expect to participate in BHM events. What we strived to achieve was to create opportunities for the community to teach and learn about black history and the impact black people have had in our society,” he wrote in an email.

Evans said that the idea of diversity and inclusion are “not new.”

“Diversity and inclusion is kind of synonymous to the idea of integration. And when you think about it, what does inclusion really mean? It’s allowing someone to come into your space. It’s not diversity, inclusion and uplift, it’s not diversity, inclusion and longevity, it’s not diversity and inclusion and acclimation,” he said.

Evans said that though Lafayette claims to include students of color, they often fail to help those students “flourish.”

“You value diversity and inclusion, but do you value acclimating students from all over, especially students of color and black students, into an environment where they are not necessarily, they were never the ideal … [Lafayette is] welcoming me, but what else are you doing to make me want to stay and to make me want to flourish,” he added.

“After Feb. 28, are you still going to support that black student who needs support because they were coming from an underserved community?” Evan asked of the Lafayette community.