A name can tell a story that runs deep, often changing understandings of history.

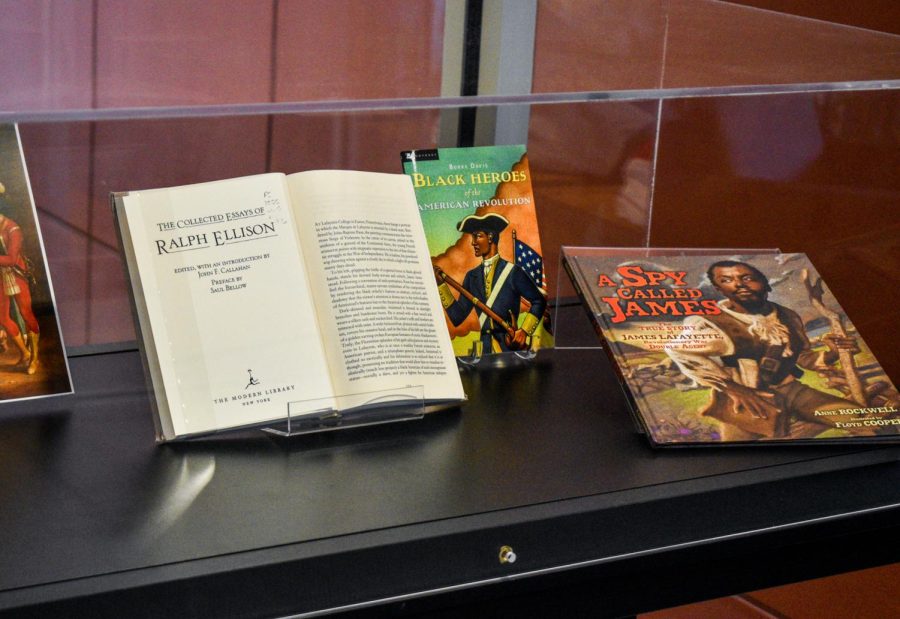

For Black History Month, Thomas Lannon, director of Special Collections & College Archives, created an exhibit in Skillman Library to tell the story of James Armistead Lafayette, a Black spy who supported the Patriots and the Marquis de Lafayette during the American Revolution.

James Armistead Lafayette, born a slave in Virginia, was bestowed the surname Armistead at birth by his enslaver, as was common in the time period. Eventually, however, citizens began referring to him with the surname Lafayette after the Marquis de Lafayette wrote a testimony granting him his pension and subsequent freedom.

“James served as a spy during the Battle of Yorktown and provided information to Lafayette that made the Battle of Yorktown possible … the culminating battle of the American Revolution,” Lannon said.

Working as a double agent, James Lafayette feigned loyalty to the British while actually supporting the Patriots.

“Cornwall, the British general, at some point sees him and says, ‘I thought he was on our side,’ but he wasn’t,” Lannon said. “He infiltrated to the highest authority of the British command, which shows he was a good spy … and ultimately is a hero for the American Revolution as a Black Patriot.”

Despite his important role in the war, James Lafayette was not recognized in the 1855 text “The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution,” which is displayed in the exhibit.

“What we’re trying to do is see if James appears in any of the books in the 19th century. James isn’t in this book in 1855 and that’s mysterious. Why is James not in that book?” Lannon asked.

He speculated on potential reasons as to why he was not included, such as the New England author’s lack of access to Virginia history and James Lafayette’s role as a spy, but the true reason remains unknown.

It wasn’t until 1942 that James Lafayette’s story appears, when historian L. P. Jackson wrote a book about Virginia soldiers during the American Revolution. At a similar time, Carter G. Woodson, a scholar and historian, founded what has now grown to be Black History Month.

“The story of James is entwined with Black History Month … because the efforts to uncover Black Patriots brought up James … [It] was all done in the same time period as the origins of Black History Month,” Lannon said.

James Lafayette’s story continued when, in 1973, the National Portrait Gallery hosted an exhibit that displayed the painting “Lafayette at Yorktown,” which currently hangs in the William Arts Center. Created by Jean-Baptiste Le Paon around 1783, this painting depicts the Marquis standing beside a Black man who is holding a horse.

“It’s a weird twist of fate, but they said that was James in the painting. But it’s not James because it was painted in France and James never went to France. And James operated as a spy and never would have dressed in this method,” Lannon said.

As a result, James Lafayette began to be portrayed not as an ally and supporter of the Marquis, but rather as a slave to him, even though it is not actually James Lafayette in the painting.

“To say James Lafayette is there as Lafayette’s servant is to deny him as a heroic, fearless patriot. James, who is really like a hero of the American Revolution, is not always given that credit because all the story goes to Lafayette,” Lannon said.

“The scholarship around the American Revolution and around the idea of race is changing and so the character of James has evolved, and I’m just trying to move it forward, so we can think more about the character of James and maybe just call him James and not James Lafayette or James Armistead Lafayette because those identities come from his proximity to … white authority and not on his own achievement, but even the word James is still loaded,” Lannon said.

Despite these recent findings, the college has yet to change the description of this painting.

“The college still hasn’t really caught up to some of the advanced scholarship because we still call that picture James Armistead Lafayette,” Lannon said.

While much of James Lafayette’s story still remains unknown, scholars like Lannon continue to find new information through the study of rare books and documents. The exhibit can be found in room 209 of Skillman Library throughout the rest of the month.