Graphic by Aaron Levenson ‘15

Glory and prestige accompany the status of being an elite college athlete. But that status exacts its own toll with a bill that may not be paid for decades, but comes in the form of lingering pain and debilitation.

It’s not just the pain of ailing ligaments and past broken bones. It’s the sleeplessness and depression that come years after graduating, and at rates much higher than their non-athlete counterparts.

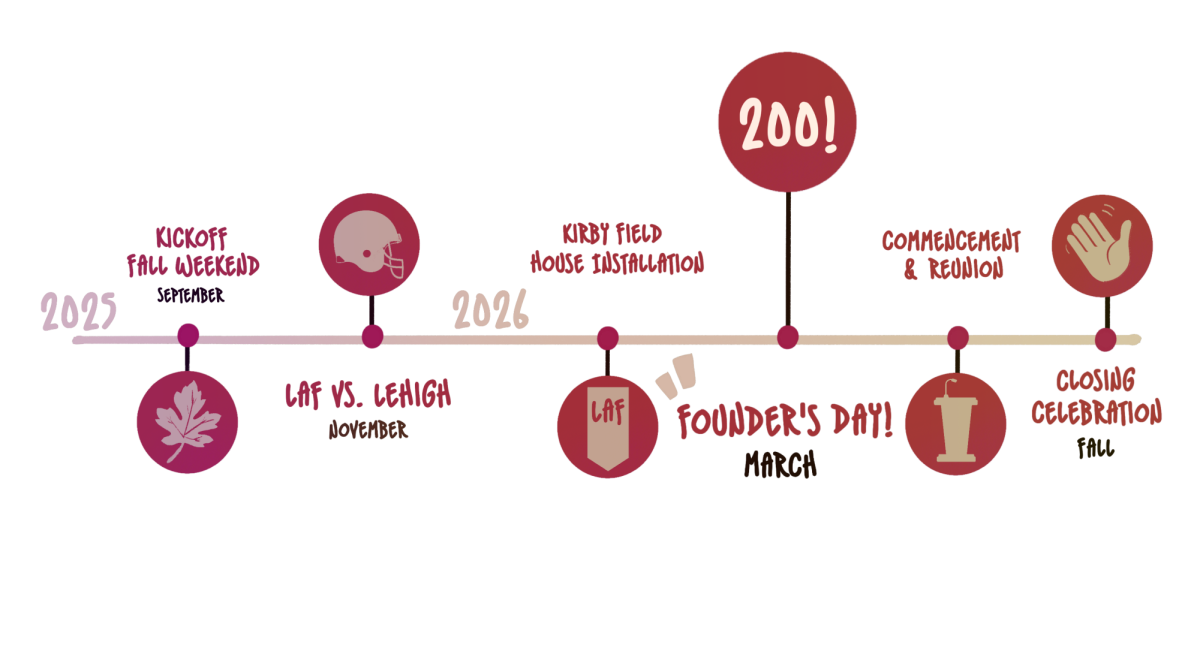

An Indiana University study released on March 3 and published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine studied 232 former Division I athletes and 225 non-collegiate athletes and found that the DI athletes are much more likely to have health issues later in life. Those non-collegiate athletes participated in recreational, club, or intramural sports in their time at college. The participants were between the ages 40 and 65.

Janet Simon, a doctoral candidate in the IU School of Public Health-Bloomington’s Department of Kinesiology, led the research team.

“I met a former Division I athlete who was talking to me about the pain he is in and how he has trouble walking up the stairs,” Simon said. “It got me thinking; are there others out there like him? Is this the norm for former athletes?”

The athletes were from various sports and each athlete answered questionnaires in self-report format, Simon said. Injuries were reported as either major or chronic. Major injuries were defined as a time loss situation whereas a chronic injury was defined by overuse. Nearly seven in ten athletes reported suffering a major injury and 50 percent reported suffering a chronic injury. The numbers were 28 and 26 percent respectively for non-athletes.

“Sports encourage physical activity, which help promote a healthy lifestyle. Moderate activity and exercise should be encouraged,” the study concluded. “However, the demands of Division I athletics may result in injuries that linger into adulthood and possibly make participants incapable of staying active as they age, thereby lowering their HRQoL [health-related quality of life].”

Simon mentioned in the study and numerous interviews that NCAA Division I schools offer their athletes access to trainers and other conditioning experts in addition to high quality equipment. But when these services are no longer available upon graduation, athletes often times do not maintain their physical condition achieved in college.

Specific injuries were not reported, but the most common injuries athletes suffer today are knee and head injuries, most notably concussions.

Both the National Football League and the NCAA are in legal battles over concussion lawsuits filed by former players.

The NFL paid $765 million in 2013 to settle thousands of lawsuits over head injuries. The former players and their families attested that the NFL failed to disclose information that multiple head injuries can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a disease that causes depression, headaches, loss of memory and disturbance of mental functioning.

The NCAA was actually formed in 1906 as a response to the deaths of 19 student-athletes that all played collegiate football. Sixty-five former college athletes are currently suing the NCAA over its handling of concussions. Only three are not former football players. These lawsuits are said to be representative of the college players who do not go on to the NFL.

“As this research was only on Division I athletes it may not translate to professional athletes,” Simon said.

There were a number of limitations in the study including that its results were garnered from self-report format. Forty percent of the athletes were previously football players and there were also more male athletes (167) than female athletes (65).

Regardless, evidence is steadily mounting of the later life perils of high intensity athletics and the calls for additional research are growing louder.

“We need to do more research especially longitudinal studies following athletes for many years and seeing how they progress,” Simon said. “We also need to work on implementing intervention programs to see if we can improve these numbers.”

Simon is working on expanding the study to compare how athletes in different sports fared against football as well as measuring the participants’ present day health in laboratory settings.