Months before George Santos was booted from Congress last Friday, nearly 200 of his coworkers wanted him gone, but they twice failed to muster the necessary votes. That was until the House Ethics Committee last month issued a damning 56-page report that uncovered evidence that Santos, already facing 23 felony charges, swindled donors into funding his Botox and OnlyFans habits among many other misdeeds.

The House eventually had enough.

In large part due to the Ethics Committee, Santos, who until last week collected a $174,000 salary and a taxpayer-funded health insurance plan, is now banished to the dark corners of Cameo.

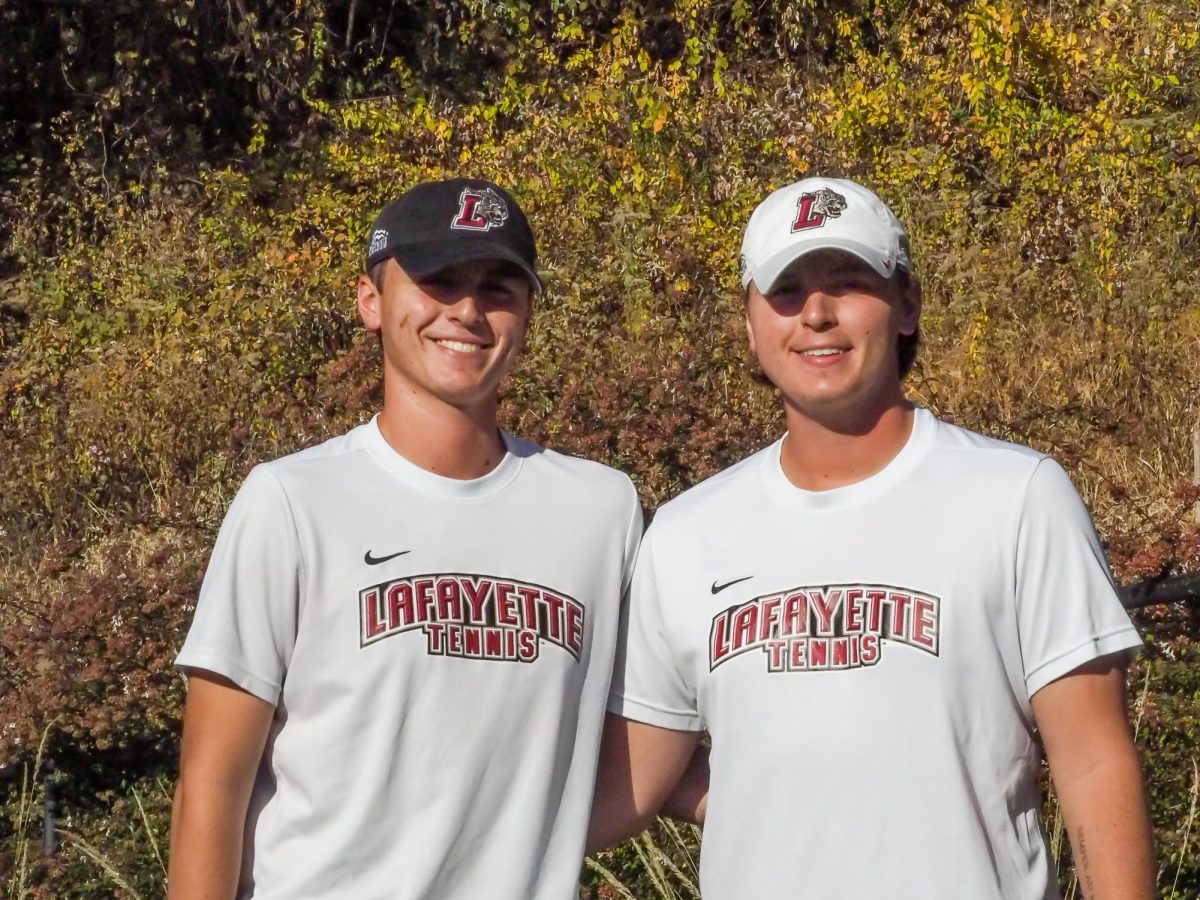

“I’m very proud of the work that was done on the Santos matter,” Rep. Susan Wild, the top Democrat on the Ethics Committee whose district includes Easton, said in an interview on Monday. “It was the result of nine months of really intensive work by the Ethics staff and multiple hearings and meetings of the ISC, the investigative subcommittee.”

While the Ethics Committee has captured national headlines over the past few weeks, much of its work rarely causes chatter beyond Capitol Hill, in large part because most of it is confidential.

Confidentiality “preserves the integrity of the committee because we’re not trying the case in the press, so to speak,” according to Wild, who briefly chaired Ethics during the last House session.

“We don’t have members of the public trying to lobby us to do this or do that because they don’t know what we’re working on,” she said.

In addition to investigations, Wild explained that the committee reviews the financial disclosure statements of members, senior staffers and candidates. They also provide training to the aforementioned groups on how to do their jobs within the confines of House rules and the law.

“A lot of the work is done by nonpartisan staff,” Wild said. “Some of the nitty-gritty of things that fall under the jurisdiction of Ethics Committee don’t really get addressed by the members of Congress.”

While many congressional candidates run on a pledge to hold government to account, most “run as fast as they can the other way” from the Ethics Committee upon getting elected, according to Wild. She said she sought out an Ethics assignment after her 2018 election, following in the footsteps of her predecessor, Republican Charlie Dent. Dent previously chaired the committee.

“People thought I was a little bit crazy,” she said.

Government and law professor John Kincaid explained that Ethics does not have any authority over legislation, making it an unattractive committee assignment.

“Ethics is like being on a housekeeping committee,” Kincaid said. “You get a lot of blowback from members if you’re starting to investigate them, so it’s a very touchy issue.”

Indeed, members of the Ethics Committee are tasked with poring through the personal records of their coworkers, a sometimes uncomfortable task according to Wild.

“There was one situation where because I was so close on a personal level with a member that I felt that, if it came to be a full-fledged investigation, I would need to recuse myself,” she said. “It did not turn out to be a full-fledged investigation.”

Probes are not the only tricky waters that Ethics members must navigate. The committee has faced scrutiny for lacking transparency and failing to address misconduct beyond financial impropriety. It has additionally earned a reputation for snail-paced investigations – the first committee report with Wild’s name on it stemmed from an investigation that predated her congressional career by five and half years.

Kincaid said that because Ethics is ultimately composed of politicians, its decisions can be political, pointing to its decision to pursue an investigation into Santos, a widely-reviled Republican. At the same time, the committee failed to open an inquiry into Rep. Jamaal Bowman, a New York Democrat who pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor after pulling a House office building fire alarm.

Bowman was eventually censured by the House on Thursday.

“That’s sort of what you expect,” Kincaid said. “That goes with the territory.”

Wild has often brushed off criticism of the committee by noting that its even partisan split, unique in Congress, ensures that any investigation must clear a high bar.

“We’re being called upon to take some sort of action adverse to a member of Congress,” Wild said. “The idea is that you should have to get at least one person from the other side of the aisle so that it doesn’t just become a partisan quest to punish somebody.”