Photographs by Tatianna Troxell ‘16

Students, professors and avid poetry fans piled into Kirby Hall on Wednesday, March 12 to listen to a reading from Natasha Tretheway.

Recently named the United States Poet Laureate in 2012 and a winner of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, Natasha is a professor of English and Creative Writing at Emory University where she also directs the Creative Writing Program.

I was afraid for a brief moment we would be subject to a long reading of poems that would be difficult to decipher and appreciate in just a single listening.

I was dead wrong.

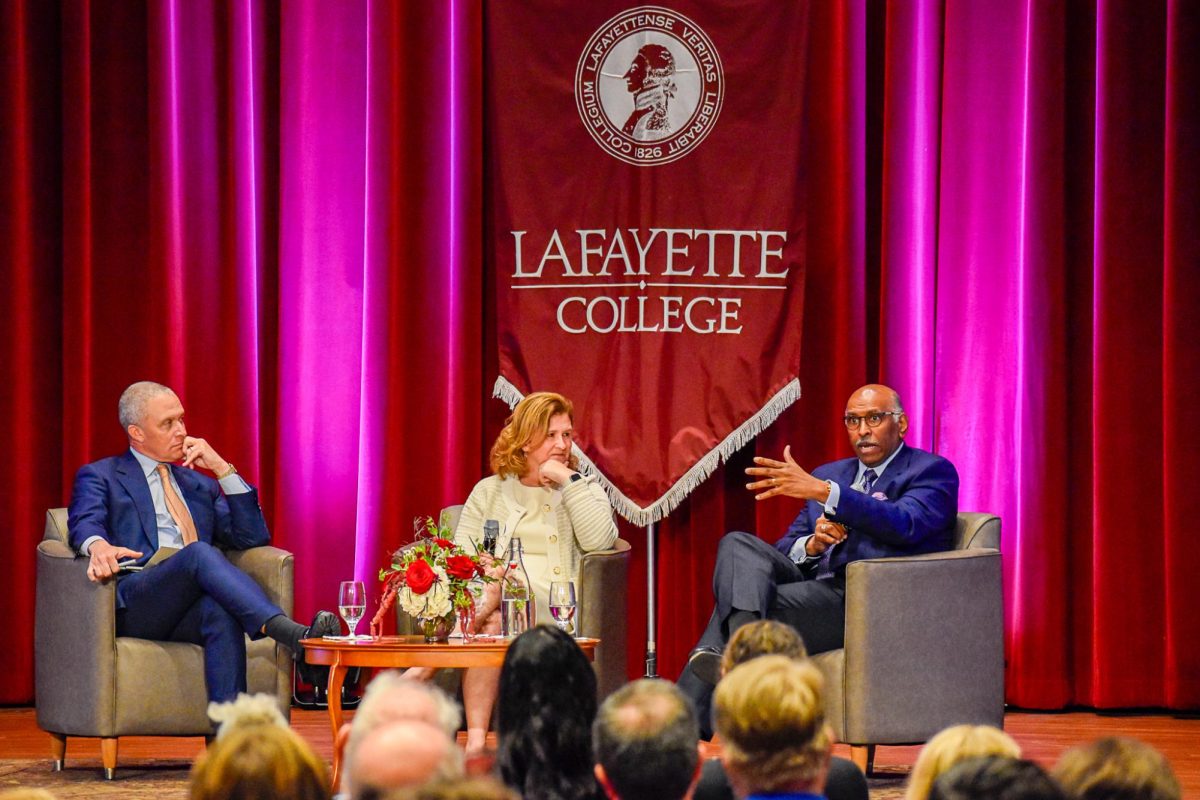

After an introduction by Professor Lee Upton, Lafayette’s Writer-in-Residence and English Professor, Trethewey sauntered up the podium and began to contextualize her poems.

“I was born in Mississippi to a mixed-race couple when that was still illegal,” she said. This proved a key fact to understanding her poetry, much of which explores race and identity. Such poems include “Miscegenation,” about her parent’s marriage, and “Miracle of the Black Leg,” an analysis of a popular medieval tale where a white man’s amputated leg is miraculously replaced with that of a dead Ethiopian.

As Trethewey progressed, her poems showcased an acute awareness of racial politics and sensitivity to a history of discrimination against people of mixed race. In the intense and visceral “Taxonomy,” she described the grim “equation of blood,” a way of classifying mixed-race children based off of the race of their parents.

Her poems also explored her rocky relationship with her father. In “Elegy for My Father,” she eulogized her actually-not-at-all-dead father preemptively, writing about a day spent fishing with him:

. . . I can tell you now

that I tried to take it all in, record it

for an elegy I’d write – one day –

when the time came. Your daughter,

I was that ruthless.

Her frank discussion of her relationship with her father culminated in her final poem of the reading, “Enlightenment,” which details a long-standing argument with her father over Thomas Jefferson while at Monticello:

whispering to my father: This is where

we split up. I’ll head around to the back.

When he laughs, I know he’s grateful

I’ve made a joke of it, this history

that links us – white father, black daughter-

even as it renders us other to each other.

Trethewey’s poetry goes further than merely reminding us that racial tension exists as much as ever in America – it renders it personally in the relationship between a daughter and her father in a way that makes it real, immediate, and new.

“Poetry allows us across time and space to hear each other,” she said in explaining the back story to one of her poems. “Poetry remains the sacred language that allows us to connect.”

Indeed, on a campus where it’s so difficult to discuss race, Trethewey’s poetry is perhaps exactly what we need – a window into understanding each other.