By Jessica Carr

Contributing Writer

Shylock is one of the most venomous examples of antisemitism. However, the re-performance of “The Merchant of Venice” invites us to analyze the value of revisiting such a playand its complexity.

Shylock is a moneylender who demands a deathly penalty for Antonio the merchant’s failure to repay a loan.Antonio’s friend Bassanio, thanks to his new rich wife Portia, offers Shylock over twice what is owed him. Shylock refuses, insisting on the letter of the law in contrast to pleas for love. Antonio and Bassanio each willfully offer themselves as sacrifices in place of the other.

Historically, the Church permitted Jews to charge interestdue to the economic necessity of loans, while prohibiting Christians to charge interest andprohibiting Jews from land ownership and many occupations other than moneylending. The Church later ended this prohibition, and charging interest became a central practice of capitalism.

There is also an allegorical message about the supersession of Christianity over Judaism: Jews, who established a covenant (literally a contract) with God in the Hebrew Bible (the Christian Old Testament), were offered a new covenant, twice as valuable and characterized by love, established by the sacrifice of Jesus in place of all humanity. Shylock’s insistence on the literal terms of his contract suggest the unwillingness of all Jews to except a spiritual covenant of love and friendship in place of Jewish law, a covenant which never paid off from Shakespeare’s Christian perspective.

If this were the message of “The Merchant of Venice,” would the play be worth revisiting? We recoil at these tropes. However, the play stands as part of a “Western canon.”So does it belong in our canon? Can its re-performance lead us to re-view it, subverting the message Shakespeare offered? If the play makes us uncomfortable, why? Is it Shylock, or does the centrality of Shakespeare suggest as much about our cultural formation as about Shakespeare? If we reject Shylock, what other stereotypes do we accept?

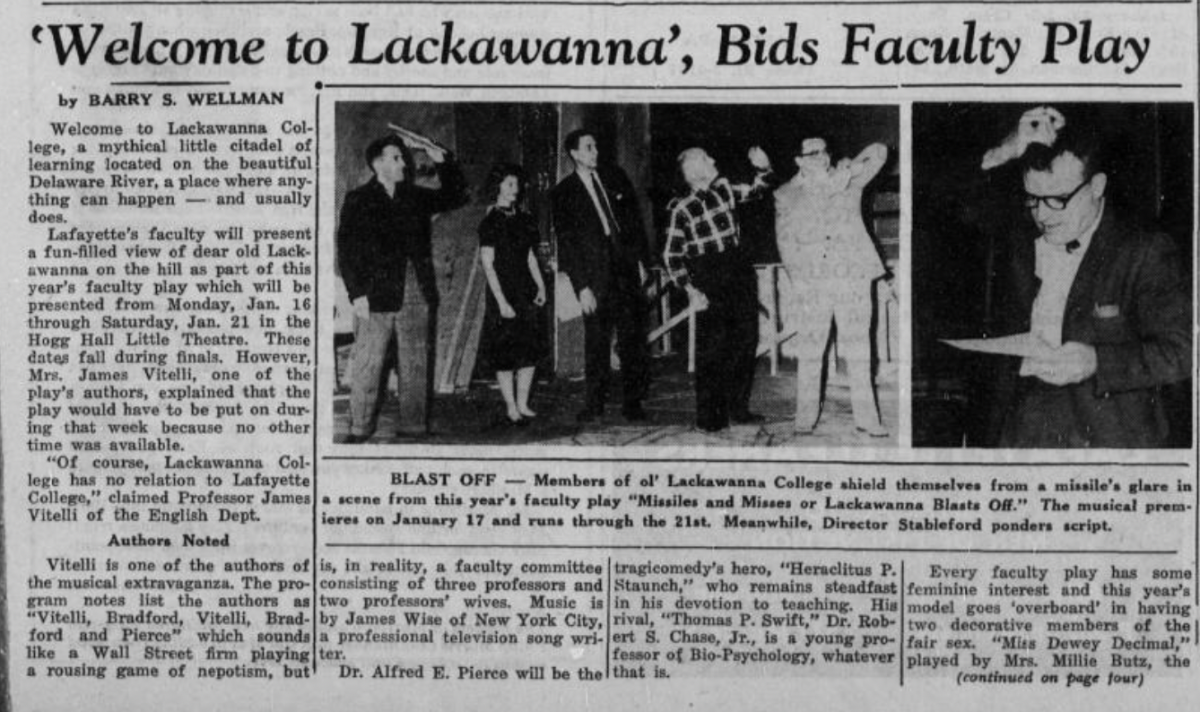

Lafayette re-staged “The Merchant of Venice” in 1938 Italy. Main characters worefascist uniforms. This implied the hypocrisy of critiquing Jews as legal literalists when Christians dressed as authoritarians. Furthermore, through non-verbal cues, this staging suggested love between Antonio and his friend as neither platonic nor Christianagape, but between two gay men. This served as comic relief throughout the play (what do we think when such a relationship makes us laugh?) and is rooted in ambiguities of love that Shakespeare implied.Yet older interpretations saw Antonio as the only one in love, and our understanding of sexuality differs from Shakespeare’s.The newly represented relationship, the fascist dress and pink armband Antonio wears in the last scenesuggest new interpretations. Shylock wore a Star of David, and we know Nazis, who would ally with and then occupy Italy, would persecute Antonio and Shylock. It is worth noting that while Mussolini’s fascist regime initially allied with the Nazis, Mussolini and Italians generally refused to participate in deportation of Jews. Antisemitic legislation was enacted but rarely enforced. Only when Nazis occupied Italy in 1943 did deportations of Jews begin.

If this staging resists antisemitism, have we rejected antisemitism entirely or displaced it? Scholars have noted similarity to antisemitism from legal responses of Antonin Scalia on homosexuality to representations of Arabs and Muslims. This “Orientalism” features in “Merchant”: Portia’s first two suitors, Princes of Morocco and Aragon (Bassanioin disguise?) wore robes and spoke with accents. Do we cringe at Shylock but laugh and accept the image of these two princes? Are we in on a ruse, or do we perpetuate stereotypes similar to antisemitism in our responses to culture, politics and social networks?

“The Merchant of Venice”deserves re-performance because re-stagingopens these questions. If we refuse to stage it, we lose the complex reevaluations made possible only through its performance. In its reception – its re-staging and our new reactions – itcan be transformed. Although“Merchant”is canonically a Comedy, Lafayette’s performance offered no happy ending. We may have been relieved to see Antonio survive the trial and laughedthroughout the play, but this re-performance transformed the play intoTragedy. We mourn Antonio as well as Shylock’s sadness, reflecting on the violence of history.