Three Black men who shaped Lafayette College

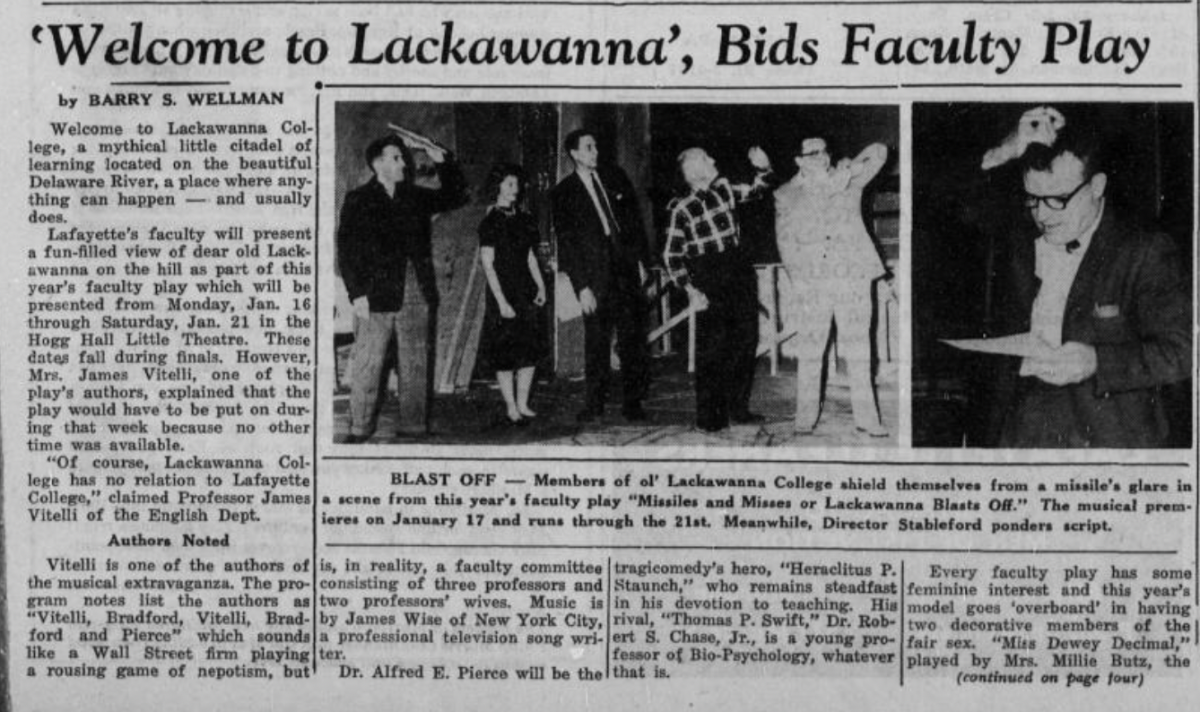

David Showell ’51 was the catalyst for Lafayette’s boycott of the 1949 Sun Bowl (Photo courtesy of Lafayette College Special Collections and Archives)

February 11, 2022

Since Lafayette’s beginnings on College Hill, Black men have been at the center of some of the most critical stories about the college.

Robert Young, Lafayette’s director of Intercultural Development, detailed the history of David and Washington McDonough. In 1838, the two brothers who were African-American slaves from Louisiana were sent to Lafayette College by John McDonough, who was the biggest slave owner in New Orleans. Young explains how the McDonough brothers were sent to Lafayette College to be educated and then back sent to Africa to “civilize” native Africans, and they made an impact the moment they set foot on campus. They were so notable that even Margaret Junkin, American poet and daughter of Lafayette’s first and third president, was amazed by David McDonough in particular.

“They had pocket watches, they spoke multiple languages,” Young said. “People were just kind of just astonished by their presence, their demeanor, their energy, their intellect. Because again, they were slaves.”

However, letters between the McDonough brothers and their slave master showed signs of resistance. While Washington McDonough was happy to fulfill John’s wishes and go to Liberia, David wrote that he would instead stay in the northern United States because he believed that he deserved the same rights that his white counterparts did.

“Washington decided he would go back to Liberia,” Young said of the younger McDonough. “David stayed at Lafayette, but he decided that he wanted to go into medicine. So then he connected with folks and he ended up going to what is now the Columbia Medical Hospital. [He] became the first Black doctor at Columbia Hospital, to then become the first Black doctor to have their own hospital in Harlem.”

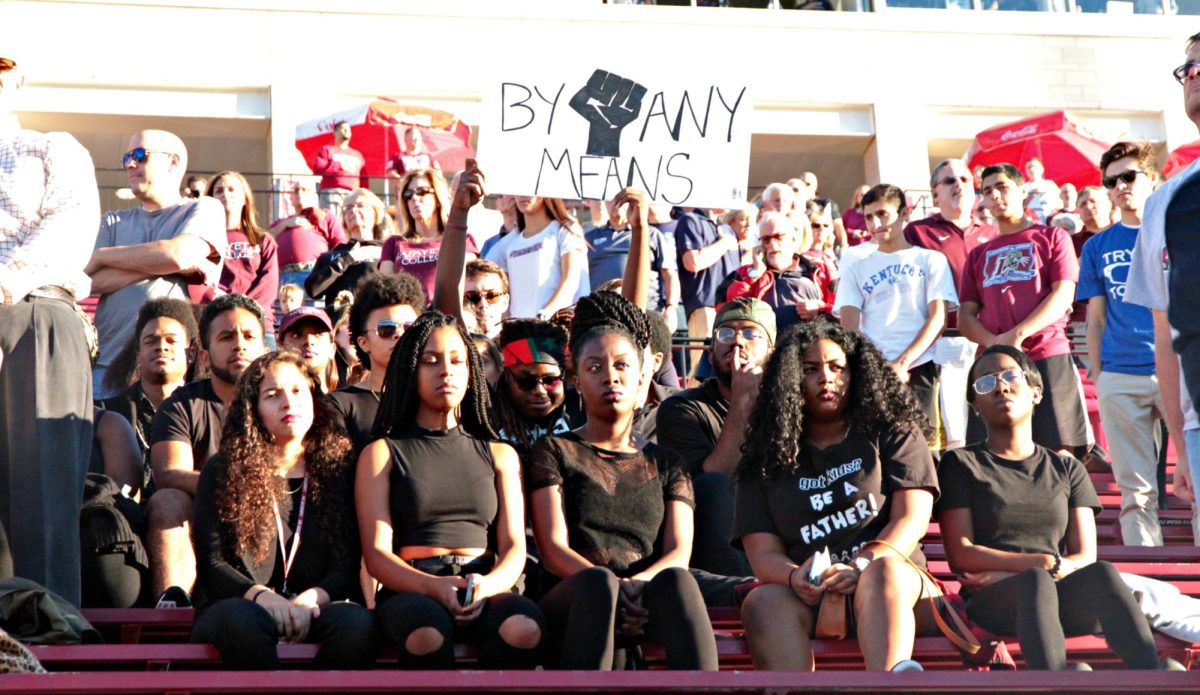

The 1949 Sun Bowl incident was another key moment in the experience of Black Americans at Lafayette College. English Professor Christopher Phillips said that the Sun Bowl invitation was significant for the school, which would have seen the Leopards play against the Texas Longhorns. However, when Lafayette wanted to bring David Showell ‘51, the lone Black football player to El Paso for the game, they were told he could not play.

“When the faculty voted to decline the invitation, the students immediately organized a protest and marched to the president’s house, where he was having dinner,” Phillips said. “He came to the door and explained to the students that the reason for declining the invitation was that David Showell, a former Tuskegee Airman and a star on the team, would not be allowed to play due to Jim Crow laws in Texas governing sporting events.”

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of World War II Black military pilots.

Phillips said the students then took their protest downtown, now in agreement with the faculty and directing their protest against the Texas law. The students’ efforts helped the incident gain national media attention. Phillips added that the residents of El Paso were so embarrassed that they successfully lobbied the state to change the law.

Young concluded by pointing out how Americans shouldn’t wait until February to commemorate the history of African-Americans.

“We shouldn’t wait until a month to give somebody a spotlight. We should celebrate the intersectionality of all people in the community,” Young said. “If we can understand and unpack the intersectionality of a mechanical engineer who’s also a double major in art history, we should also be able to understand the identity and cultural heritage of a person, seen and unseen, every day at Lafayette.”

An exhibition to the McDonough brothers named “Tales of Our Brothers” is in the lobby of Pardee Hall.