To type or not to type: The debate over student use of technology in classrooms

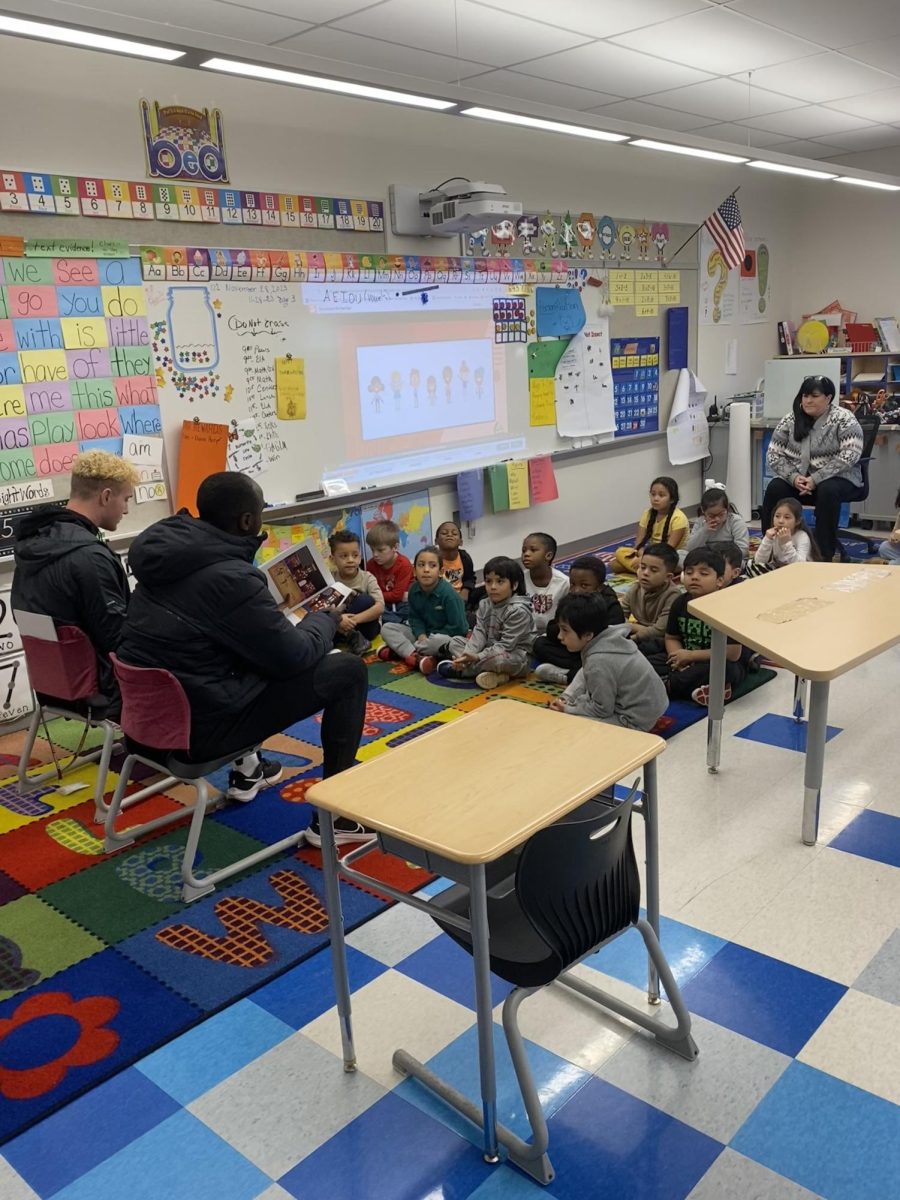

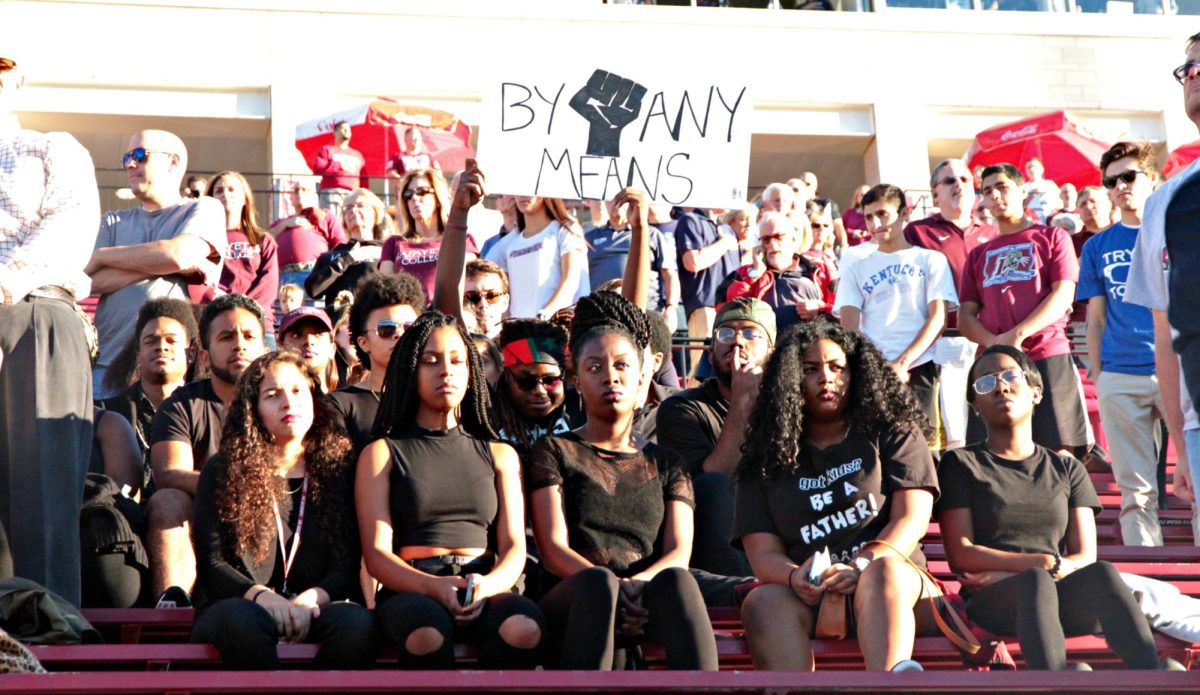

A common objection that professors have to technology in the classroom is that it acts as a distraction. (Photo by Emma Sylvester ’25 for The Lafayette)

March 4, 2022

From submitting papers online to watching videos for homework, technology has become an integral part of education at every level. But, for some Lafayette professors, the question still remains: does technology belong in the classroom?

Religious Studies Professor Youshaa Patel highlighted the temptation for students to look up other information while using a device in the classroom.

“I think [technology] can harm the student in the sense of denying that student the opportunity to hear something of value,” he said.

In Patel’s classroom, students only use personal devices when working with electronic reading material.

“If we’re not doing something that’s specific to the particular reading, then I ask them to keep the focus on the class, especially for discussion classes,” Patel said.

Monika Rice, a professor of Jewish studies and Russian and East European studies, also only allows device use if students have purchased class texts virtually.

“[Student use of technology] really impedes their participation and possibility of immersion in the content of the lessons,” Rice said. “The ubiquitousness of technology should not presuppose it being used at every possible moment, because that will affect your relationship with people and your relationship with education.”

Both Rice and Patel accommodate students who require computers or tablets in class but feel that, as professors, they have a responsibility to foster a distraction-free environment. Professor Timothy Laquintano of the English department agreed but also recognizes that it lies with the students to use technology responsibly.

“I don’t think in the foreseeable future, at least over the next decade…that [devices] are going anywhere, and so people actually do need to develop healthy relationships,” Laquintano said.

Laquintano also acknowledged, however, that once personal devices are allowed in the classroom, it is difficult to monitor how they’re being used.

“What I’ve found is that it’s either a total and complete ban with accommodations for disabilities, or basically let students do what they want because there’s no way to regulate it and no way to do much of anything once you allow it,” Laquintano said.

The conversation surrounding accommodations is one of the more complex aspects of the technology debate. For example, some professors fear that by allowing only students with learning accommodations to use technology, it forces those students to reveal information that they might rather keep quiet.

“It forces students with disabilities to kind of disclose that by being the exception to it,” Laquintano said.

In response to this, Patel highlighted the gap between his policy and the way he enforces it.

“You can have a policy, and with regard to enforcement, have some leniency,” he said. “That creates some space where some students feel comfortable using their laptop, and it doesn’t appear, from my perspective, that those students are sort of being outed for having an accommodation.”

Some cite inequality of access to technology as a reason to keep it out of the classroom. For Laquintano, in order to properly and fairly integrate technology into the curriculum, a universal technology policy would be necessary.

“I think we should have a laptop policy because it could be built into student financial aid packages,” he explained.

This would be a step toward solving the problem of unequal access to technology among students. Bowdoin College, a private liberal arts college in Maine, recently implemented a similar policy that will provide students with a MacBook Pro, iPad Mini and Apple Pencil.

Patel echoed the call for an institution-wide technology policy, specifically one that would provide tablets to all students. Patel prefers tablets to laptops because students would not be looking down and hiding behind the screen as much as with a laptop.

“If Lafayette did distribute tablets to all students, I would be more open. In fact, I would endorse all students using tablets in class, because I think that can save money with regard to having physical books, and it’s less onerous for students then to remember ‘did I bring that book, and did I forget this book?’ if everything is there on your tablet,” Patel said.

Laquintano agreed that technology can help “bring down the cost of instructional materials if they’re digital.”

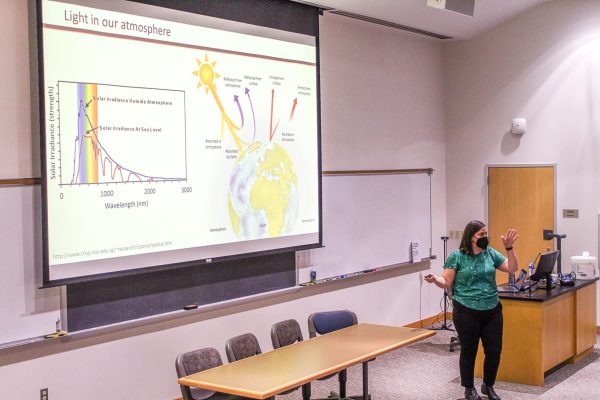

Mechanical Engineering Professor Jenn Rossmann, who teaches courses on the development of technology, sees both the positive and negative aspects of incorporating technology into the classroom.

She recalled the ways in which technology expanded the different ways in which students could participate in class, such as the chat feature on Zoom, over the Covid-19 pandemic when classes were all virtual

“Now that we’re back in person, I look for ways to sort of do what the chat did to give those other avenues to participate, and technology is really good for that,” Rossmann said. “It’s much better to have those other avenues for a student to participate in class conversation, and sometimes to do it asynchronously.”

Despite favoring “tools that enhance accessibility and that improve access to knowledge,” Rossmann is also wary of blindly allowing all types of technology into the classroom, particularly services that collect data.

“Often technology offers such tremendous convenience that we sort of unthinkingly grant it access to data that we might actually if we stopped to think about it, not want to allow,” Rossmann said.

“We haven’t had the sort of societal conversations that would let us decide thoughtfully and in an informed way about how some private company should be using this kind of data,” Rossmann continued. “And instead of having those conversations, we’ve just allowed it to become embedded in our educational system.”