Professors comment on critical race theory and its many misconceptions

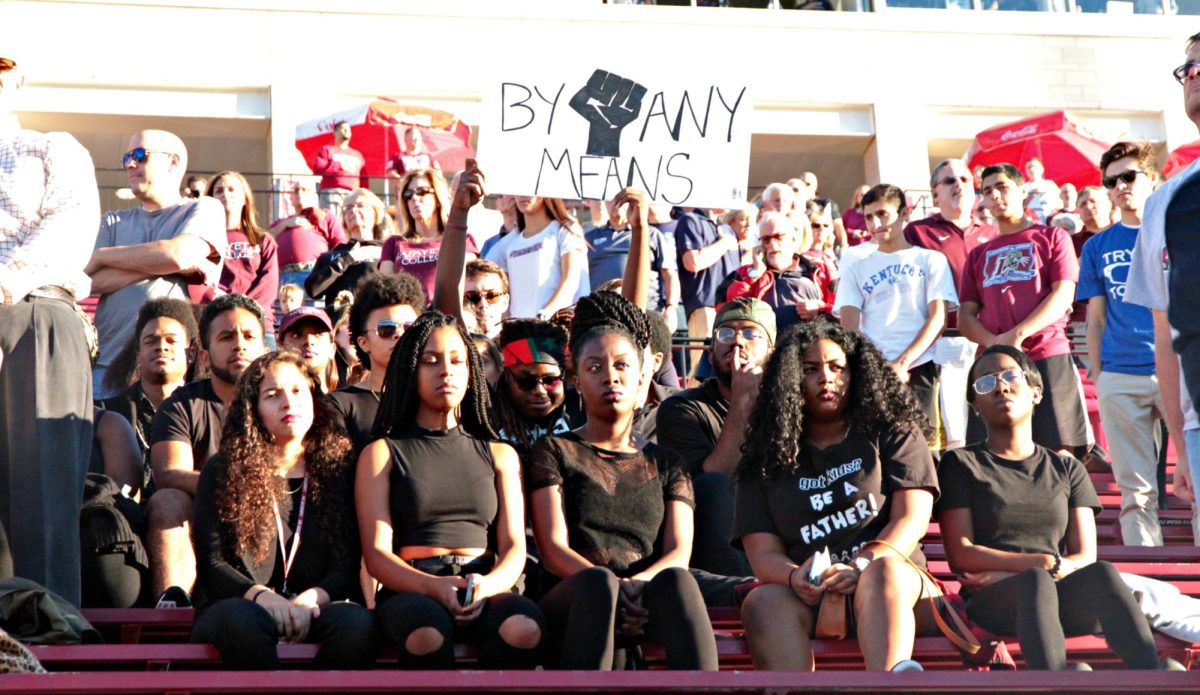

Photo by Trebor Maitin for The Lafayette

History Professor Jeremy Zallen noted that many legislatures throughout the country are debating whether to ban critical race theory. (Photo by Trebor Maitin ’24 for The Lafayette)

March 11, 2022

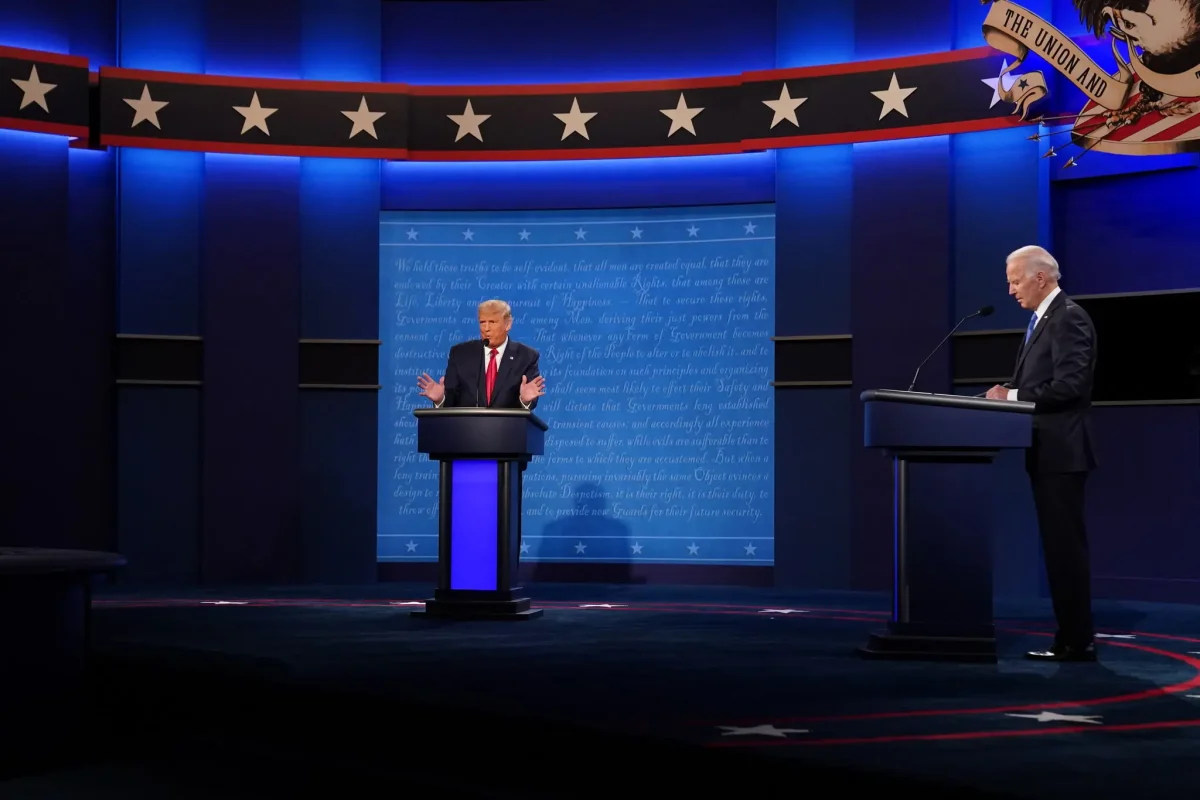

Critical race theory (CRT) has emerged as a wedge issue in recent months with activists on either side of the political spectrum pushing or disparaging its teachings. The theory is a cross-disciplinary intellectual and social movement of civil-rights scholars and activists who seek to examine the intersection of race and law in the United States and to challenge mainstream American liberal approaches to racial justice. One major theme in the discussion surrounding CRT is the pervasiveness of misconceptions surrounding it.

“It is hard to say there is a single coherent theory as opposed to a number of principles that have been developed by a number of people,” Government and Law Professor John Kincaid said.

A newer concept in critical race theory is intersectionality, which concerns the intersection of race, class, gender and disability. CRT also argues that race is a social construct instead of a biological phenomenon and that racism has an institutional manifestation such as disparity within social welfare programs.

“The Social Security System sets the same retirement age for when you are eligible for full benefits, the impact, however, is that African Americans, on average, have a shorter life span,” Kincaid said. “So they either pass away before the retirement age or they pass away earlier and get the benefits for fewer years than the average white person.”

While the college offers little to no classes centered around the critical race theory, many professors opt to integrate the material and acknowledge systemic and institutional racism in their lectures.

“I don’t use CRT-related theories in my classes, but we are always talking about overlapping structures of domination and power and how sex, gender, race and class have been historically challenged and changed over time,” History Professor Jeremy Zallen said.

Numerous state legislatures around the nation are debating bills seeking to ban critical race theory in classrooms. It can be argued that this is indicative of the broader and impending issue of censorship and protection of free speech.

“There are states passing laws banning teachers from talking about certain topics or banning books, that is a much scarier thing that is happening,” Zallen said. “The laws everywhere around the nation surrounding CRT or anything related to gender, race and class being taught in classes are vague and have a silencing effect.”

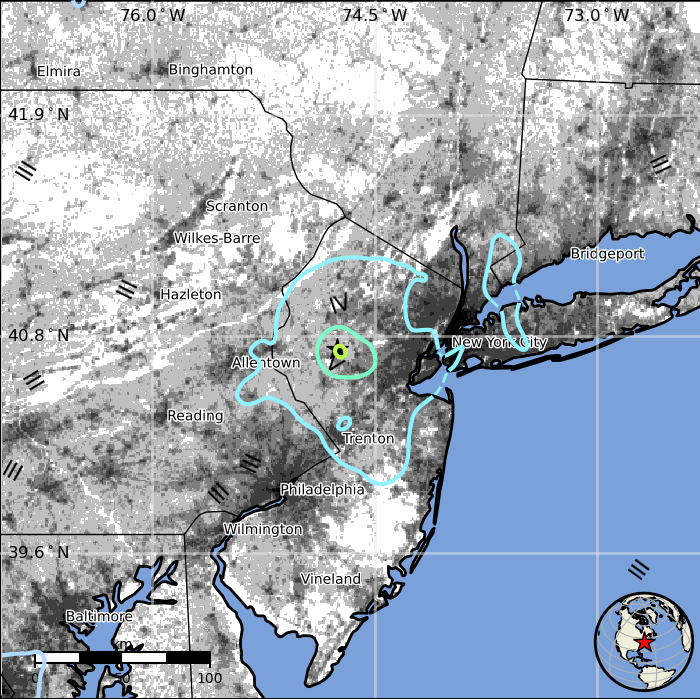

According to the Pennsylvania Capital-Star, a so-called school transparency bill, which would require districts to post all curriculum and course material online, has gained popularity among Republican lawmakers. In the Lehigh Valley, too, the topic of teaching about race in the classrooms has drawn controversy; East Penn schools settled with a family who sued over lessons about white privilege and systemic racism, The Morning Call reported.

The debate over the integration of CRT in school curriculums also raises the question of historical accuracy and whether existing units cover systemic and institutional inequalities.

“The opposition to CRT mostly came out during the pandemic when a lot of parents were seeing what their kids were learning about and they were upset to see that they were learning about the United States’ racist history, not a perfect history,” Zallen said. “They would rather see a patriotic version of the past.”

Mariatou Coulibaly ’23, secretary for the Association of Black Collegians, said that one’s understanding of American history is impacted if one doesn’t confront the past with a critical lens.

“The very possibility of white children understanding the violence that is whiteness has pushed parents, school board members and politicians to ban all forms of critical race theory within classrooms across various states,” Coulibaly said. “This is the very definition of erasure. If policymakers are prioritizing the innocence of white children over the experiences of their Black counterparts then what becomes of our understanding of American history?”

Echoing these comments, Zallen asked “the question is what do we want to teach our children about? Do we want to teach them a sanitized version of the past that isn’t true?”

While the debate over the integration of critical race theory in schools around the nation still remains a prominent political issue, many classes and student groups on campus aim to educate peers about racial injustice and existing disparities.