Sullivan Removal Coalition develops goals beyond plaque removal

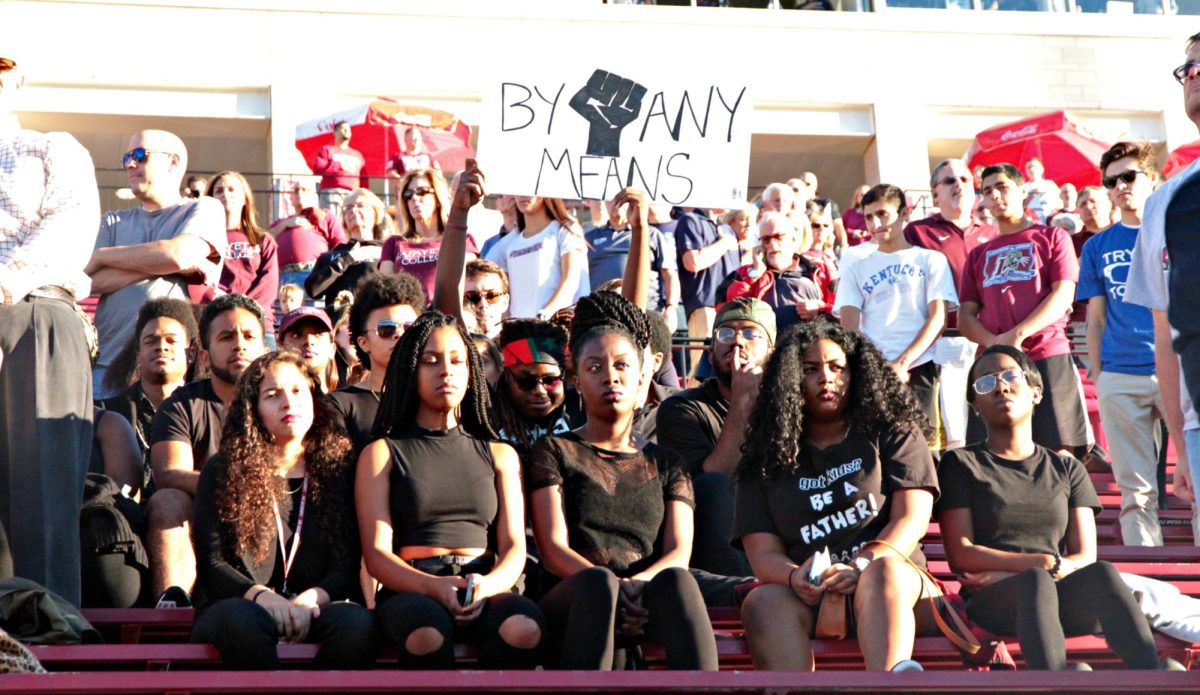

On March 23, students gathered together, learning about the memorial and future action items. (Photo courtesy of Ariel Haber-Fawcett ’24)

April 8, 2022

A second letter demanding the removal of the controversial Sullivan memorial along with several other objectives relating to Indigenous concerns will be sent to the Lafayette administration in May.

The memorial in question was installed on June 18, 1900, by the George Taylor Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), which is based in Easton. The plaque commemorates the path along which General John Sullivan marched to wage a scorched-earth campaign against the Iroquois who led devastating raids against American settlers. It is located near the Delta Upsilon fraternity house on Sullivan Road.

The letter, part of a final project for a class entitled Voices of Environmental Justice, was written by Lizzie Diacik ‘23 and Tessa Landon ‘22. This letter led to the two students to collaborate with Ariel Haber-Fawcett ‘24, Abigail Schaus ‘24 and a number of other students to form the Sullivan Removal Coalition.

This was not the first time that students had learned about the plaque through their curriculum, nor was it the first time that students had advocated for its removal. Multiple students submitted a letter to the administration in 2019. Two years later, the situation remained unchanged, and students protested against the memorial again. Through the formation of the coalition, however, a variety of different voices have begun pushing for deeper changes to improve Lafayette’s current lack of recognition of Native American history.

Some members of the coalition expressed uncertainty over ownership of the plaque, specifically whether Lafayette would be allowed to enforce its removal or if that power lies with the DAR. Haber-Fawcett said that if the plaque could not be removed, putting up an additional plaque acknowledging its problematic language would be the ideal next move.

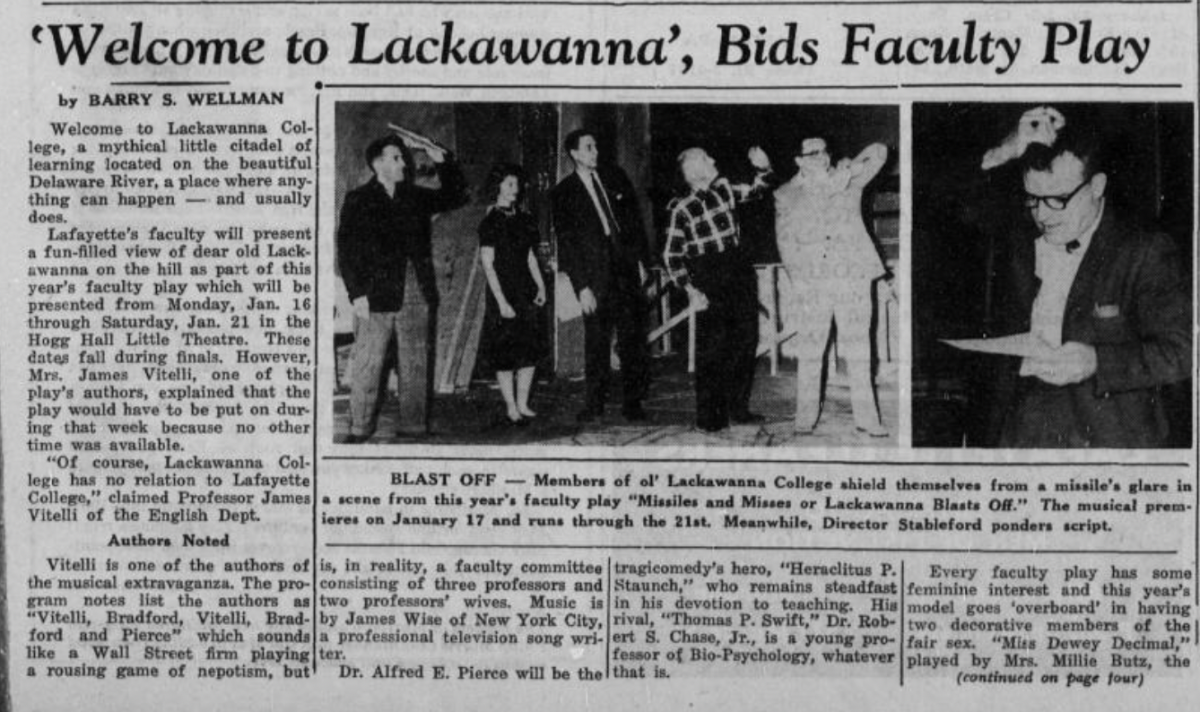

On March 23, students and faculty members filled Rockwell 362 at the first meeting of the coalition, where speakers explained the history of the plaque and the motivation behind advocating for its removal.

One speaker at the event was Oneniotekó:wa Maracle ‘25, a Native American student whose first name means The Great Standing Rock. A member of the Mohawk nation, Maracle is from Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory and currently resides in Akwesasne Mohawk Territory. In his slides, Maracle detailed his objections to the plaque’s presence on campus due to his personal connection to the events it recounts.

“The people that General Sullivan seeked to thoroughly destroy were/are the Haudenosaunee (People of The Longhouse),” the slides stated. “The Haudenosaunee more commonly known as the Iroquois Confederacy consists of 6 nations…We are living breathing people who still exist in modern society.”

The meeting included members from a variety of different organizations and groups on-campus that had an interest in removing the plaque and going further with Native American activism.

Haber-Fawcett said that members built upon pre-existing momentum in the movement to get all of these groups in the same room.

Schaus echoed this sentiment.

“It was kind of just the ripple effect of seeing what other courses and folks have knowledge and experience with this,” Schaus said. “We’re not associated with any particular club or department, we’re not exclusively students, or exclusively faculty, but it’s just this coalition of folks who are informed and passionate about creating institutional change.”

The coalition pointed to the power of language in discussing historical events and their impacts. Diacik said that she first heard of the plaque through Environmental Studies Visiting Professor Paul Guernsey, who touched on it in his curriculum.

“That plaque was discussed in the course because it represents an active ecocide against the Haudenosaunee Confederacy which was carried out by General Sullivan on orders from Washington,” Guernsey said.

Guernsey described the all-encompassing goal of the campaign, which intended to eradicate Indigenous populations for the benefit of their colonizers.

“It wasn’t just warfare,” Guernsey said. “It was actually intended to basically purify the landscape of Indigenous people to eradicate them, to destroy their villages, to destroy their crops, to destroy all their relations, their social relations, their ecological relations.”

The coalition believes that the act of removing the plaque, while necessary, serves only as a symbolic first step and not as a sufficient decolonizing tool.

“Of course, the plaque is doing real harm by existing,” Guernsey said. “But…just simply removing it doesn’t do anything to kind of redress this history.”

Diacik and Landon wrote their letter after initially thinking about writing a land acknowledgment. Similar to Guernsey, Diacik said that she realized it was a performative action to simply acknowledge harm without acting to change it.

“What does it matter to say ‘we respect you’ if all of the actions we show are the opposite?” Diacik asked.

For her, this belief extends to Lafayette’s follow-through on their core values, which include diversity and inclusion.

With that in mind, the coalition meeting included discussion of action points that are currently being solidified and fleshed out. Some objectives include forming a Native Studies department, requiring the history of the Lenni Lenape to be taught to students, giving free tuition to all Lenni Lenape students and reinvesting the endowment to avoid fossil fuels.

Maracle explained that a department dedicated to Native Studies would be beneficial in terms of resources and education, both for him and the larger community.

“I just feel like there’s not a lot of resources for me here, being like the only Native student at Lafayette that I know of…I don’t think that there’s any other Mohawk or any sort of Native students at Lafayette,” Maracle said.

Guernsey said that community building can be difficult when there is no space solely dedicated to a specific group, such as Native American students or faculty members on campus.

“Part of the problem in not having a Native Studies program or department is that Native students and native faculty…have no way of being visible,” Guernsey said.

Maracle detailed the breadth and diversity found in different Indigenous groups.

“The people on the land that we live on, the Lenape people, [are] completely different from my people,” Maracle said. “There’s even stuff for me to learn in Native Studies programs because I really only know about Mohawk stuff, Haudenosaunee stuff, because that’s who I am.”

Maracle said that many people do not have an accurate understanding of what Native American culture consists of and how it operates.

“That was one of the big reasons for me,” Maracle said. “Joining [the coalition] as well was like, bring more knowledge on what Native American people are, how we still live in today’s society, because I feel like, it’s also thought of as we’re like an extinct people.”

The coalition is also placing value on structuring its own longevity. Given that students cycle out by graduating, any effort to affect long-term change by forming a department or reshaping the curriculum would require a continuous effort from new members each year.

Correction 4/13/2022: A previous version of this story spelled the name of Oneniotekó:wa Maracle without a colon.

Louis Zulli • Apr 9, 2022 at 6:23 am

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=136117

Sarah Beck • Apr 8, 2022 at 8:58 am

I am proud of the student body for taking this on. I hope that the Coalition will involve faculty and staff once they feel ready; I for one would love to get involved.