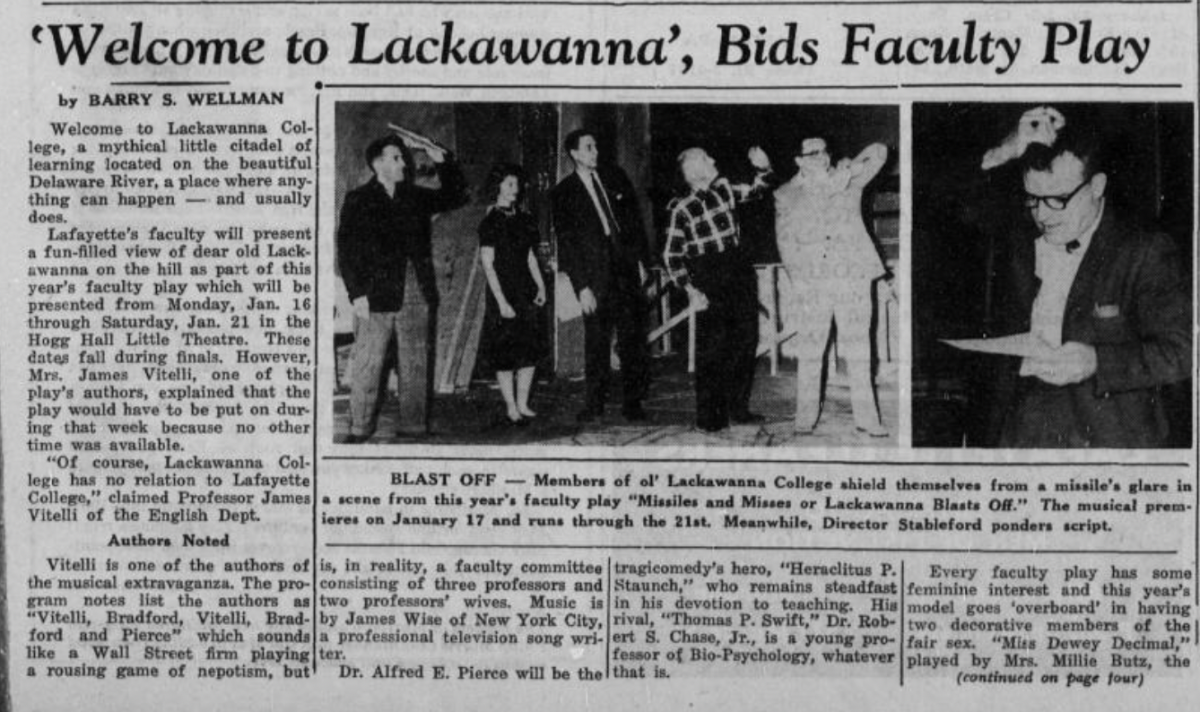

‘Tōkaidō Road’ art exhibit brings 19th century Japan to life

Utagawa Hiroshige’s exhibit transports the audience into Japan’s military past. (Photo by Pierson White ’24)

October 22, 2021

The Williams Center for the Arts currently has an exhibition of prints on display created nearly 200 years ago.

The series, Utagawa Hiroshige’s “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road,” captures the point of view of an ancient daimyo, or feudal lord, traveling between the Japanese cities Edo and Kyoto.

The works feature sweeping landscapes, commoners’ everyday lives and a surprising brilliance of color for something made in the 1830s. The images are numbered so that visitors can experience the journey chronologically, as it was experienced by those who originally walked by them.

According to Rico Reyes, the director of galleries and curator of museums at Lafayette, “if you’re interested in 19th Century everyday life in Japan, this is a really good exhibition to look at.”

The exhibition was curated by Art Professor Ingrid Furniss and EXCEL scholar Nicholas Scaglione ’22.

Preoccupied with the sights and splendors of travel, the series is nevertheless enmeshed in the shogunate which ruled Japan at the time.

“In a lot of [the prints] you’ll see these processions of people, and these were supposed to be daimyo processions,” Scaglione said. “There [were] no depictions of daimyos; it was illegal. The daimyo himself is never shown because the government would not have been happy with him.”

The economics of feudal Japan is also on display through the works. Reyes pointed out that “if the governing system is either aristocratic or royalty, a lot of the art that’s made is for the court. The shogun, the emperor, et cetera are [usually] the ones who have the money to pay artists.”

Art made in a printmaking studio is relatively cheap and reproducible, so it can be geared towards the common people. Such is the case with “Tōkaidō Road,” which is why the focal points of the prints are often common people. This, however, results in cheaper materials and more imperfections.

The history of “Tōkaidō Road” is visible through its own imperfections. Scaglione said of a black dot on a print, “that is actually a mistake on the block, just a little piece of wood that they left when they were making it. If you look at later versions of this print, that little black mark isn’t there, and that’s a way you can tell [these] are early versions of it.”

Those who visit the exhibition can see the influence of these prints on popular culture today. Fans of the rock band Weezer might recognize print #16 as the cover of their sophomore album “Pinkerton.”

The exhibition will be on display in the Williams Center for the Arts until Dec. 18.