The past, present and future of teaching Black literature at Lafayette

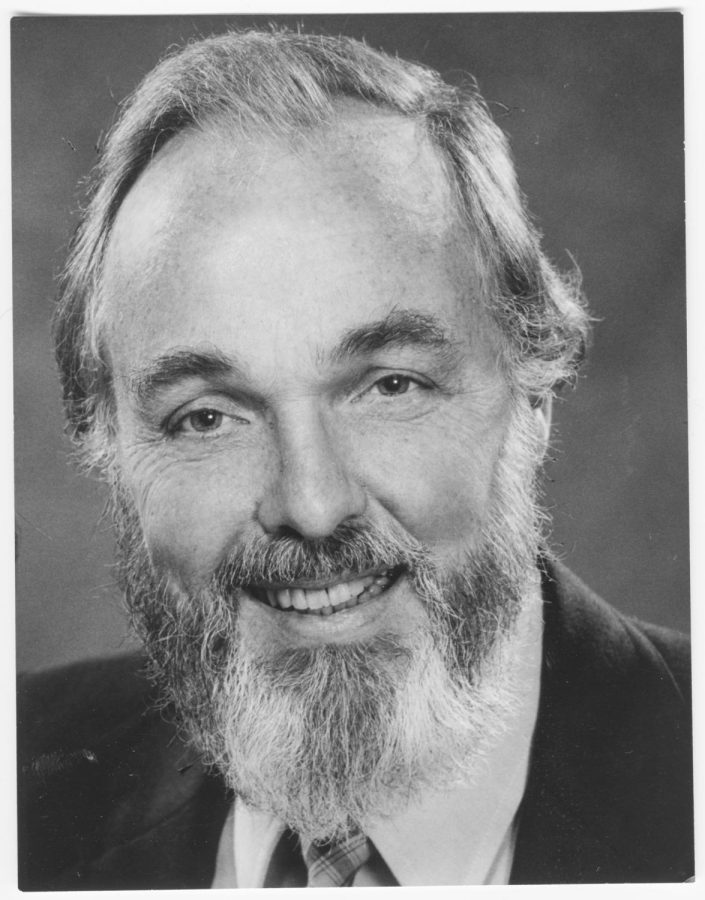

English Professor Fred Closs ’51 taught one of the first classes at Lafayette focused on Black writers and thinkers. (Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository)

March 4, 2022

The name Fred Closs may ring a bell for students because of the Closs Residency, which provides funding for distinguished writers to visit Lafayette’s campus. However, you may not know that Fred Closs ’51 was also one of the first professors at Lafayette to teach a class centered around Black literature.

Closs became a professor at Lafayette’s English department in 1964. In addition to teaching writing and literature courses like Satire, Modern British Fiction and Twentieth-Century Poetry, Closs taught an American Civilization course titled The Black Man in America.

According to its course description, The Black Man in America aimed to “explore the social, political, and economic aspects of Black Power; the sources and consequences of racial prejudice; the achievements and shortcomings of the Civil Rights movement; and the black ghetto.”

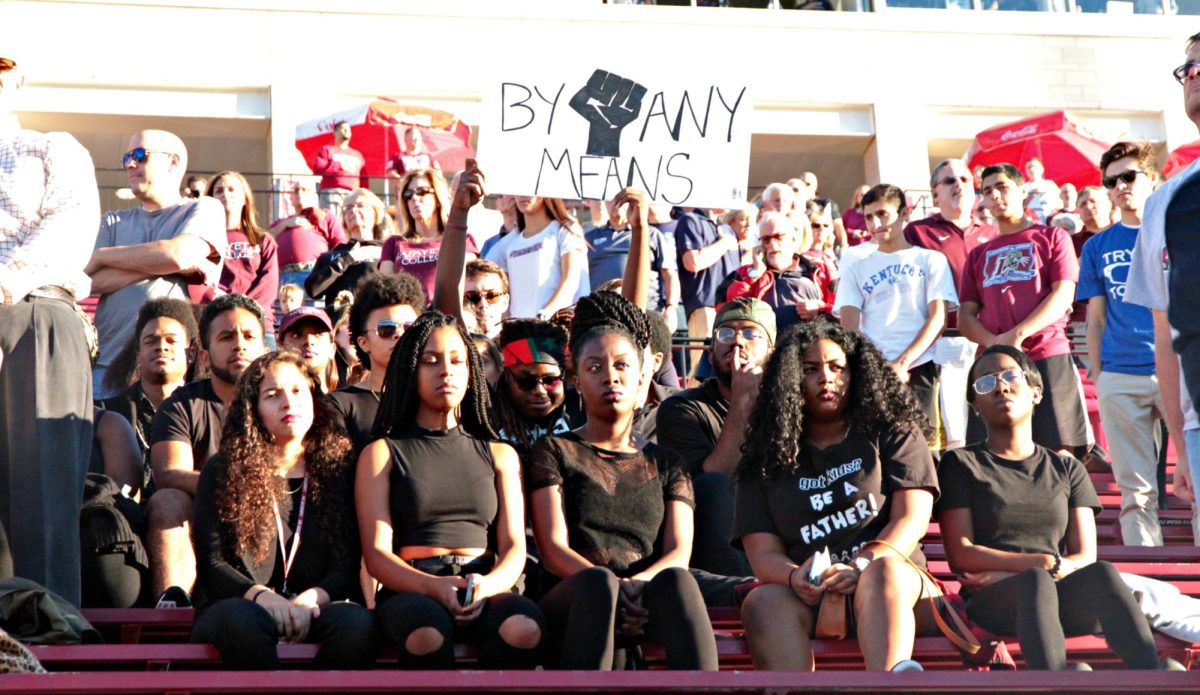

Before Closs began teaching The Black Man in America in 1969, there were no classes in Lafayette’s English or American Civilization department that focused on Black literature. The course was established during a time when colleges across the country were receiving pressure from Black students to offer courses focused on the Black experience. At Lafayette, the Association of Black Collegians (ABC) had just released their Black Manifesto, which included a demand for the formation of a Black Studies program.

Closs brought many distinguished guest speakers to the class, including writer Ralph Ellison, the renowned author of “Invisible Man.” He also worked with ABC to host their spring seminar series in 1970, which featured discussions about the Black Panthers, being Black on an all-white campus and Black participation in the American political system.

Undoubtedly, Closs’s contributions introduced Black writers and issues to a curriculum that was, at the time, overwhelmingly white. However, English professors at Lafayette agree that the department still has work to do when it comes to offering a comprehensive education of Black literature.

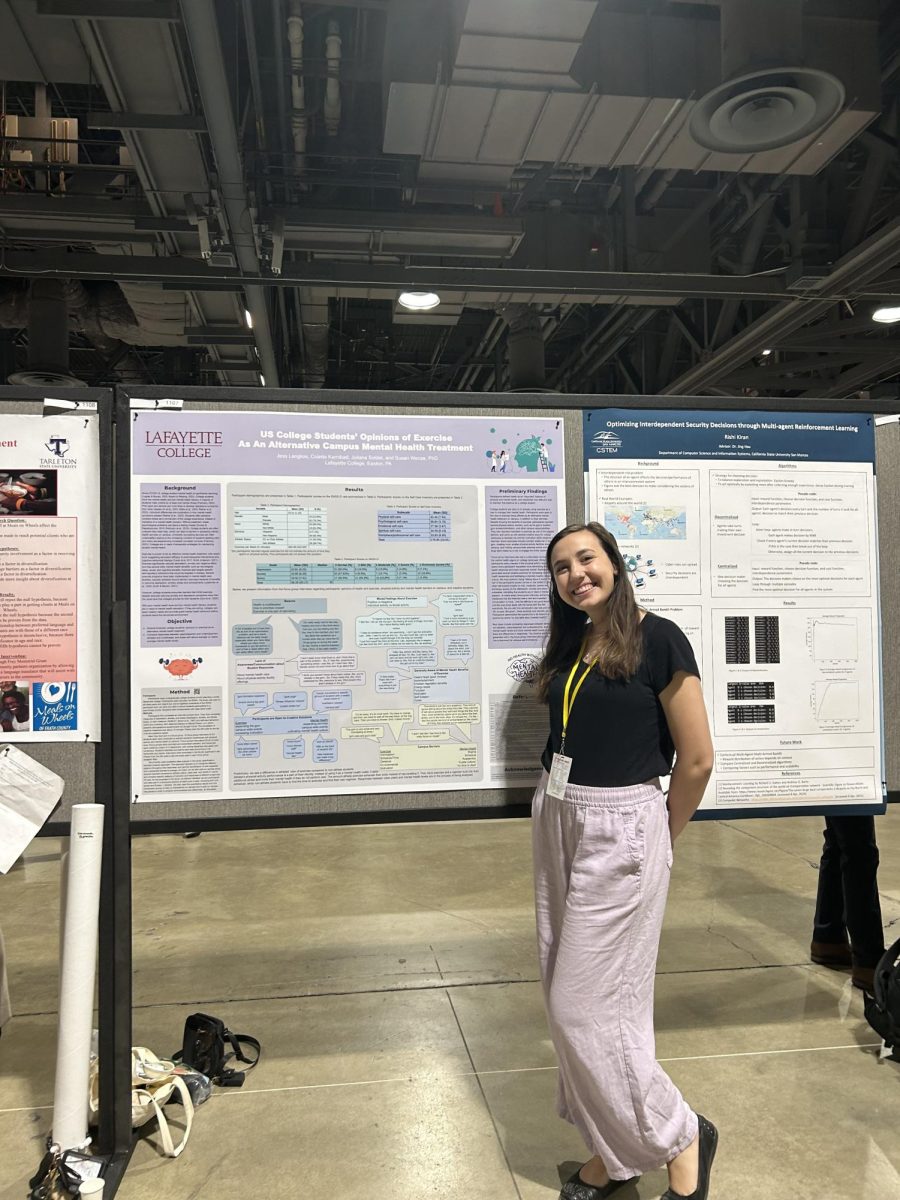

English Professor Randi Gill-Sadler has taught a wide range of courses at Lafayette about Black literature, including Black Writers, Black Feminist Theory and Literature and Film, a course on protest and rebellion in African American literature and film.

She pointed out that Closs’s course, The Black Man in America, approached the Black experience from a patriarchal lens. In this aspect, Lafayette has made progress.

“I’m happy to see, at least in my time being here, more attention to Black women’s writing, more attention to the innovations of Black feminist literature and Black feminist literary criticism, which I think lends itself to thinking more with Black queer studies, Black trans studies,” Gill-Sadler said.

Gill-Sadler also acknowledged that many in the English department are reorienting their syllabi to address conversations around race. However, despite these steps forward, she said that there is still a pervasive “commitment to whiteness.”

English Professor Mikael Awake, who is currently teaching the course Special Topics in Black Literature: Ghostwriting, agreed with this sentiment.

“The English department at Lafayette prides itself on being the oldest English department in the United States. This, to me, is not the kind of thing I would take pride in. Why not take pride in innovation?” Awake said. “I think there’s something very colonial about that history. There’s that desire for firstness.”

Indeed, even the newspaper in your hands boasts at the top that it is “the oldest college newspaper in Pennsylvania.”

Gill-Sadler explained the ways in which courses about Black writing and white writing continue to be treated differently. She cited the term “British literature” as an example.

“We know that there’s a long history of Black British writers, but we don’t make clear the ethnic angle of a British literature class,” Gill-Sadler said. “That’s because we assume that Britishness is analogous to whiteness.”

“I don’t think that the study of literature is neutral or colorblind,” she said. “I think that we have to be very explicit and honest about our investments and how we approach the study of literature.”

For instance, Gill-Sadler has also taught Literary History, which is a required course for English majors. Her version of the course focuses on the Black Arts Movement. She recalled hearing from a student that they didn’t realize the course would be about African American literature.

“There’s this cognitive dissonance where students believe that if they were to learn literary history, African American lit would not be included, or that African American lit needs to be announced as something separate from, quote-unquote, ‘literature,’” Gill-Sadler said. “I think the biggest obstacle is the assumption that literary studies is interested in white writers and white literature.”

Awake argued that Black literature is essential to an English curriculum beyond performative displays of diversity, equity and inclusion.

“Within the house of Black literature, there are so many rooms. It contains multitudes. It is the world. It is global. It is everything, in a certain sense,” Awake said. “It doesn’t only exist in counter-position to whiteness, and it doesn’t only exist because it’s important for white people to understand.”

Gill-Sadler agreed, arguing that Black literature is crucial knowledge for students who are interested in having a robust understanding of literature.

“My issue with the contemporary moment is that people will say, ‘Oh, because all of these killings are happening, we need to read Black literature,’ which creates this very insidious framework that Black writing only accompanies a kind of lived Black tragedy,” she said. “But I think the contributions of Black writers are so vast in terms of what Black writers have done with genre, what they’ve done with form, what they’ve done with language, what they’ve done with poetics.”

Gill-Sadler said that beyond adding courses and revising syllabi, the college also needs to provide the material resources for Black literary study.

“What would it mean to give [professors of Black literature] the money to do the kind of research they need? What would it mean to invest in student publishing? What would it mean to invest in symposia? What would it mean to commit to providing resources so that graduated students could go to graduate school in literary studies, could apply broadly to programs to visit literary archives?” Gill-Sadler said.

Lafayette has made progress since Fred Closs’s first Black literature class over 50 years ago. However, as Gill-Sadler and Awake have pointed out, while the increased visibility of Black literature in Lafayette’s English department is a great first step, it certainly shouldn’t be the last.

Wendy Wilson-Fall • Mar 20, 2022 at 8:41 pm

As the Chair of Africana Studies, I regret that the program does not appear at all in this article, even in reference by the professors interviewed. I worry about the contradictions between individual or other departmental black futures, and the sustainability of an Africana Studies Program at Lafayette. That aside, I would agree with much that they express, with the related caveat that not to know “the black world” or “black artistic expression” or something about “Africa” is unfortunately to remain in a sort of closed room, without realizing that the future is happening outside of the windows of that room.